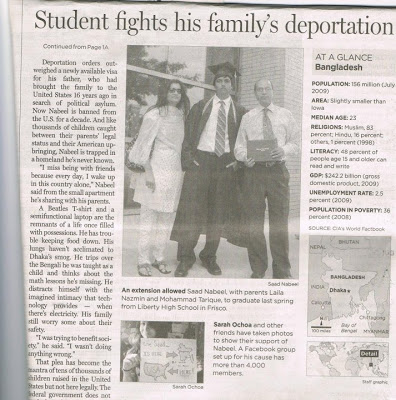

A Conversation with Saad Nabeel:

‘While Everyone Goes to College, I Go to Jail’ or How Saad Nabeel became an All-American Kid, majored in Electrical Engineering, was Thrown into Jail by the USA, deported to Bangladesh, denied Re-Entry, and Ignored by the New York Times White House Info Regime. All of This Instead of what he Really wanted, which was a Kickass Freshman Year…

[Previously on The Rag Blog: Greg Moses: Deporting Texas Student Was Big Mistake.]

By Greg Moses / The Rag Blog / August 18, 2010

The following conversation with Saad Nabeel was stitched together from more than a hundred emails during the months of July and August, 2010.

Part One: An American kid

Where were you born and when did you arrive in the USA?

SAAD: I was born in Dhaka, Bangladesh in 1991. I moved to the USA in 1994, when I was three years old.

And that was in California?

SAAD: Yes I moved to Los Angeles, California.

Do you recall those first impressions of LA? What was it like?

SAAD: Well it was my home. That’s all I knew since I have no memory of anything earlier than LA. I loved my home.

What was it about your home that you loved?

SAAD: I loved everything. Being able to play with my friends, go to school and have fun, go to all the cool places in LA with my parents. What I loved most about my home was that it was a place I knew that I was safe. It was a place I always knew would be there at the end of the day, no matter what happened.

But that changed?

SAAD: Yeah it changed when I was about to graduate from the 5th grade. Immigration forced my father to choose between returning back to Bangladesh and getting persecuted by rival political groups, or moving away from California and awaiting the approval of his green card that his brother had applied to get him.

And that’s when your family brought you to Texas?

SAAD: Yes, in 2002, a few weeks before graduating from elementary school.

So you arrived in Texas just in time for summer. What was it like for you?

SAAD: Well I was in a place where I knew no one. I had just left my entire life behind and everyone I knew in it. Much like what it feels for me now in Bangladesh.

And then you started Middle School. What was that like for you?

SAAD: I started the 6th grade in Allen, Texas. A school named Reed Elementary is where I went. Middle School began in Allen when you started 7th grade, so I was stuck in elementary for another year. Reed was interesting to say the least. Going to school in Texas is where I experienced my first taste of racism. People made racist jokes on a daily basis about me, in front of other peers.

So you found it difficult to make friends at first?

SAAD: Yeah, at first. But I quickly made friends, though the racial slurs kept on at a steady pace with the kids who were strangers.

So let’s talk about the friends for a minute and how your final year of elementary school ended.

SAAD: Well elementary school ended decently I’d say. I was good friends with most other students. Everyone generally liked me. After 6th grade we moved to our home in Frisco, Texas.

And that’s where you stayed until college?

SAAD: Yes sir.

What was it like making friends in Frisco? What was the Middle School like for you?

SAAD: It wasn’t difficult making friends in Frisco, probably because the initial shock of leaving my life behind in California had eased away. Wester Middle School was fun. Eighth grade was the best because it was easy and I knew everyone. Going to Six Flags at the end of the year with my class was also great.

As you were busy growing up, how involved were you with your family’s immigration status? Given the upsetting nature of your family’s move from California, how much did it weigh on your mind that you might have to leave the United States?

SAAD: Well I was not involved. I was told it was being taken care of since we almost always had lawyers doing some sort of work for us. I didn’t have time to be involved with immigration, because I knew nothing about it. I thought I was just a regular kid like everyone else I knew. It never occurred to me that I would have to leave America since it was my home. I was told we would eventually have our green cards.

So let’s talk about High School next. Did you go to the same High School as most of your Middle School friends? What interests did you develop there?

SAAD: I went to high school with all of my middle school class (at least for freshman year that is). I developed a keen interest in computers and everything about them. I learned everything I could about them. Other than that, hanging out with friends, going to the movies, going on dates were all the norm.

And you started your own company at that time? Tell us about that.

SAAD: That’s when I started Easy PC (for lack of a better name). I figured “why not use my skills for a job?” I found cheap website hosting, made a site, and went around trying to advertise. Got a few flyers up in classrooms of teachers I had. Made an honest buck or two.

All in all, an all-American story. Then you went off to college?

SAAD: I applied for scholarships and was pleasantly surprised to receive enough funding to get a full ride for the University of Texas at Arlington. My years of hard work in high school finally paid off.

Did you move to campus housing or commute from home?

SAAD: I moved to the on-campus apartments. Centennial Court was the name.

I looked it up online. Seems like a perfect place to live out your college years. What was that first month like in September 2009?

SAAD: It was awesome. For the first time in my life, I was living alone. I had great roommates and we always had awesome times together. Classes weren’t so hard since we had just begun. Everything was going right in my life.

And then came the turning point? What was your first notice that things had changed for you?

SAAD: I’d say the first indication was when my parents called to say that they were going to report to ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) in the morning, just as they did every month, except that day, they didn’t call me to tell me how it went.

Is that the infamous ICE office on Stemmons Freeway?

SAAD: Yes it’s the one on Stemmons.

How were you notified that this visit to ICE had turned out so differently?

SAAD: Honestly I wasn’t aware of the implications of the situation until my father was detained, and he was detained before the date that ICE allowed him on his papers. I was honestly caught up in loads of school work.

Part Two: Jail at the border

OK, so let’s focus for a minute on your experience of the events that unfolded. How did you first become aware that the situation was dire? How were you notified, and by whom? What did they say? What went through your mind?

SAAD: I first became aware of the situation on Nov. 3 when my mom called me at my apartment telling me that my father had been taken by ICE. Things didn’t really function in my head. She told me the only choices we had were to go to Canada and try to seek refuge there or to go to Bangladesh, a third-world country. I had no idea what to say about any of this. Losing my life in a heartbeat isn’t exactly something that’s easy.

Nov. 3, 2009 was a Tuesday. By that time you would have completed your mid-term assessments? How were your grades at that point?

SAAD: Actually, mid-term exams were about to start. I had an Electrical Engineering lab exam in the morning so I was up studying all day. My grades were good in my opinion. I put a lot of effort into my work.

So what did you think about your options at that point? Canada or Bangladesh?

SAAD: I didn’t want either one. I wanted to stay where I was at. I wanted to stay home. But I couldn’t let my mother go alone to Canada. I had to go with her. She’s my mother.

So you traveled with your mother from Dallas to the Canada border?

SAAD: We flew to NYC. Then my uncle drove us to the border.

Was that your father’s brother? Was he someone you had known well? What was that trip like? What was going through your head? Which border station did you approach?

SAAD: It was my father’s brother. We used to live with him when we first moved to the USA. But we had not seen each other in years. The trip was long and tiring. The only thing in my head was, “Am I really leaving everything behind?” We approached the Buffalo border.

And this was still early November 2009? As you were approaching the border at Buffalo, what was the weather like? What time of day? Did you just try to drive through, or did you park the car and approach the border station on foot?

SAAD: It was towards mid-November since it took us a while to prepare clothes, food, and other items for the trip. It was very cold the entire time. Snow on the ground everywhere we went. When we got to the border, we worked with an organization that helps immigrants who are out of status and have only Canada left as a choice. We filed paperwork with them, camped out at a one-room motel for over a week. I would sleep on the floor, my mom on the bed.

As November wore on, were you able to keep in touch with friends? What were you saying to them? What were they saying to you?

SAAD: The motel had internet, so that’s how I was able to communicate to my friends. I was telling them that I had to move to Canada. Only my closest friends knew the real deal. They helped me pack my belongings in Texas. They were all bummed out.

Do you want to talk a little about the organization that was helping you with the process? Besides filing papers and waiting for an answer, was there anything else for you and your mother to do?

SAAD: The name of it was Vive La Casa. They have a website. All my mother and I had to do was wait for the call to go to Canada, meet with her relative (in this case her uncle), and convince the border authority that their relationship was legitimate.

Her uncle?

SAAD: Yes. You need a relative to go into Canada. She was fortunate enough to have one. Although I use the term “fortunate” very loosely seeing as I’m not exactly in the best shape.

At Vive la Casa, they would call your mother’s uncle an “anchor relative”? So if we continue to use terms very loosely you had some “hope” that your passage to Canada would be approved?

SAAD: I do not know the terminology, honestly. That’s probably correct though. You are also safe to assume that I had little to no hope that we would enter Canada. Why? Because I was never able to get over the shock of leaving behind everything in my life because of immigration, for the second time — the first was the move from LA.

So what happened next?

SAAD: To make the depressing story short: we got the call that we had to go get interviewed at the border. We went there and met up with my mom’s uncle. All three of us were separated from each other into different rooms and drilled with questions. Hours upon hours later, Canadian immigration said, “we do not believe you two — my mother and her uncle — have a relationship. Sorry, but we are sending you back to U.S. immigration.”

By that time it was very late in the day? Were you able to communicate with anyone?

SAAD: I had been awake all night and they finally rejected us around 4 p.m. when the office closed. After that we were sent back to U.S. immigration and locked in a room until one in the morning or so. I was able to call one friend. That’s it.

So there you were, locked into a room with your mother for eight hours, and the Canada option was closed? What kind of room was it? What were you expecting next? How was your mother holding up?

SAAD: It was a room with a few seats, a TV, and a glass wall looking out at the other side of the building we were housed in. A lot of people were there. There was a counter at the top of the room. Behind it is where the police officers and ICE agents were. I only expected to be taken to jail. That’s what they told us when we got there. My mother was in tears the whole time.

It sounds miserable. Two weeks prior to that you had been in Texas studying for your electrical engineering midterms. Now you were a thousand miles away in New York, waiting to go to jail.

SAAD: That’s my life. While everyone goes to college, I go to jail.

And that’s where they took you next? To jail?

SAAD: Yeah. Handcuffed mother and me and took us to separate facilities.

Did you have a clear idea of why you were being jailed? I mean it seems that you were doing everything according to established procedures. Were you given any kind of hearing or any chance to get a lawyer before they handcuffed you?

SAAD: No. I had no idea what was going on. All I knew was that ICE was okay with us living in Texas. We did not get the right to a lawyer.

Did you get the impression that ICE was treating you as your mother’s child, under her supervision? Or were they treating you as an adult with full rights and privileges to be informed about what was going on with options of your own?

SAAD: I never had to report to ICE. Only my parents had to. I thought I was still under parental supervision.

Where did they take you? What did they tell you? How were you handled?

SAAD: They didn’t tell me much. Not much conversation other than, “We’re taking you to Batavia. Your mom is going to Chautauqua County Jail.” We were handled like luggage.

So they took you to the Buffalo Federal Detention Center at Batavia, New York? That’s about a one-hour drive from the city of Buffalo. Were you cuffed the whole time? Am I correct to imagine that you were pretty numb from the shock of it all?

SAAD: I was cuffed the whole time. I had not eaten or slept in 36 or so hours. It was 4:30 a.m. when I was finally stuck into the room I was to live in for the next 42 days.

Do you recall the date? I see that the Batavia detention center has three diamond-shaped pods. Did you have a sense of your location within the facility?

SAAD: It was the day before Thanksgiving. No, I had no sense of location when I was inside.

Were you alone in your cell? What was the typical day like?

SAAD: I was with 60 men in the room. A typical day was spent by doing nothing. Later on I made friends with a few people there and we played cards for five hours at a time to kill the day. I kept a 20-page journal of what was in my mind.

There were 60 beds in one room? Do you want to share a passage from that journal?

SAAD: Yes, the room had two floors with 30 people on each floor. I was prisoner number 301. The journal is a madman’s journal. It’s full of random mood swings and trauma.

Were you able to communicate with your mother, your friends, or an attorney?

SAAD: I was not able to talk to my mother or father. I was able to contact a few of my friends.

What was that like? Not being able to talk to your parents? Did your friends help to keep your spirits up?

SAAD: It made me worry about them. I knew my father could take care of himself. But my mother had never even imagined she would experience torture like this. My friends tried their best to keep my spirits up. They told me time and again to not blame my parents for what was happening.

So you were kept in jail through the holidays? Thanksgiving, Christmas, New Year?

SAAD: Yes.

Part Three: Deportee

And then you were deported? How did the deportation take place?

SAAD: Yes, I was deported. They took me out of the room. Forced me to sign papers stating I had a 10-year bar from returning to the USA. “If you do not sign what we give you, you will be criminally charged and kept in jail.” I signed the papers. They stripped me in front of another officer once again to see if I had something concealed then gave me the 42-day-old clothes I wore when I entered the facility.

I was then taken by an officer out to a van that my mother was in. We flew from the Buffalo Airport to Chicago O’Hare, then to LAX — my hometown… didn’t think that was how I would visit it — then from there to Bangkok, Thailand. In Thailand my mother and I were kept in a cell with no air conditioning, which was literally crawling with cockroaches and spiders.

Did your mother tell you how she had lived for 42 days at the Chautauqua County Jail? How long were you two kept in Thailand?

SAAD: She was devastated as expected. It’s difficult to describe the feeling honestly. It’s like walking to the gallows. She told me she was transferred three times, denied hot water, and kept behind bars. We were in Thailand for over three hours or so.

Then you were finally transported to Bangladesh for a reunion with your father? What was that like?

SAAD: Father was still in Haskell, Texas, at the Rolling Plains Prison. He came in February. My mom’s brother — uncle to me — made special arrangements with Bangladeshi immigration because if he did not, we would have been detained for three days.

Wait. So your father was still in Texas? You and your mother were deported before he was deported? And yet his status was the primary interest for immigration? Everything sounds completely mixed up to me.

SAAD: That’s completely correct. Trust me, I’m just as confused as you are.

For the record maybe we should make a note here that this section of the interview is transpiring on the day that the White House disinvited your Dallas advocate Ralph Isenberg from a fundraiser that he paid $10,000 to attend. We live in confusing times.

SAAD: It was to make it so the New York Times article was not contradicted by my case.

Yes, the Times was reporting that students like you were not being deported. There you were, a bona fide national contradiction. I’m sure we’ll come to Ralph in good time. Meanwhile, you and your mother were getting settled in Bangladesh. How did you find a place? What did you have with you? Who did you know there?

SAAD: My mom has family here. We stayed with her brother for a week or so. Then they found an apartment across the street from his. I arrived with a bag of clothes in a duffel bag. That’s all.

And you hadn’t seen Bangladesh since you were two or three? You had jet lag and culture shock? What do you recall about that first week?

SAAD: I had no memory of this place at all. It was and still is a different planet. I don’t even know the language, so 90 percent of the signs on the street were and are alien to me. Culture shock — there’s really no way to describe the feelings I had because I knew “I can’t go home.” The first week, I started getting sick, vomiting, depression, tirades against my mother, etc.

And then your father joined you? What do you recall about that reunion?

SAAD: It wasn’t one that I’m proud of. All my life I knew how to control my anger. But when you lose your entire life in front of your eyes, you don’t care anymore about control.

But what could your father have done differently? As I understand the situation from talking to Ralph, your father was very close to getting permanent residency.

SAAD: I don’t know what he could have done. All I know is that there was probably a way to avoid all of this.

When did you begin campaigning for your return to the USA? How did that begin?

SAAD: I began in March I believe. My YouTube video has the date on there (March 18, 2010). It began after I recovered mentally a bit and regained some of what made me “The Saad” back home. Everyone knows the The Saad back home, and they know that when he sets his mind to something, he makes it happen. It’s egotistical but it’s what keeps me afloat.

When do you first recall being called “The Saad”? Was it connected to a specific achievement?

SAAD: I first started calling myself The Saad in 2007 during my junior year of high school. It caught on, as much as everyone hated saying it because it added to my ego, ha ha. Teachers started calling me that at one point.

What about “The Official Group: Bring Saad Nabeel Back Home to America”? The first signature at the petition is dated March 26, 2010. And there is a Facebook page. How did all that come into existence?

SAAD: I started the Facebook Page a long time ago. I was the one who created the Official Group. I made it as a central hub for people to learn about my situation. I would stay up all night spreading around my initial deportation video and group link. Very long nights. But the PR paid off eventually when the Dallas Morning News came knocking.

Yes, I see an excellent, comprehensive story on April 5, 2010 by Morning News reporter Jessica Meyers. She describes you as “a Taco Bell aficionado and Taylor Swift fanatic.” Did she contact you via Facebook? The story is sympathetic to the unfairness of your status but not very optimistic about the chances of reversing it.

SAAD: My friends and I have been living off of Taco Bell for years now. We used to say “Taco Bell’s our second home. It’s the hand that feeds. Don’t insult it. Don’t bite the hand that feeds.”

Ah yes, I am completely and utterly in love with Taylor Swift, no arguing that. The salutatorian of my graduating class mentioned me in her speech during our graduation ceremony because of how much I loved Taylor Swift. The Dallas Morning News contacted me by Facebook first.

But before the Morning News published their story, you were contacted by WFAA reporter Steve Stoler? He interviewed you via Skype for a March 22 report. And that was a few days before the online petition was posted (or the domain name created). So the Dallas media must have seen something compelling in your story.

Stoler presented supportive on-camera comments from your Liberty High School friends who called your treatment “unfair.” And you say, “I really hope that someone in the government has a heart.” Heart and fairness? What’s wrong with asking for that?

SAAD: Yes, Steve contacted me on Facebook as well. What’s wrong with heart and fairness? I have no idea. I still can’t accept the fact that I’m stuck in Asia right now.

Speaking about heart and fairness, how did you get to know [attorney] Ralph Isenberg?

SAAD: After the Dallas Morning News article was published, Ralph contacted Jessica Meyers who wrote my article and she contacted me.

So you’ve been working with Ralph since about mid-April, 2010? What has that been like? What has Ralph been able to offer in the way of resources and strategy?

SAAD: Yes since mid-April. Working with him has been good. He has more information to share than any immigration attorney will ever tell you no matter how much you pay them. Actually he’s more knowledgeable than most attorneys.

And he helped you try to return to college this year? What was your experience of that?

SAAD: Yes, he and I worked on me returning home as fast as possible to attend SMU. Dr. Charles Baker from SMU contacted the Dallas Morning News at the same time as Ralph did and so I introduced them.

So the three of you worked on the SMU option? What was that experience like for you?

SAAD: Well it gave me hope that people hadn’t given up on me. I finally felt like I could go home.

How did the process play out over time? What things were you doing to qualify for admission to SMU and secure passport permissions to return to America for college?

SAAD: Dr. Baker would scan up the necessary documents for SMU, email them over, have me sign them, and then send them back. I qualified for SMU thanks to my ACT score. Passport permission was not given to me. I was denied my visa because my passport had an “ineligibility” on it. The U.S .Consulate told me to come back January 5, 2020.

So you visited the U.S. Consulate in Bangladesh? When was that? Did you have to fill out forms? Was there a meeting or an interview? Did they know that you had been accepted at SMU?

SAAD: I believe it was a day or two before June 30, when the Dallas Morning News pumped out a short article about it. At the consulate, I did not have to fill out any forms. It was an interview. There was a man behind a glass screen and I was on the opposite side. They knew everything. I gave them — all the paperwork, letters from SMU, etc. They didn’t care. They took one look at it and rejected me based on my passport. I don’t understand how difficult it is for the government to just fix a simple mistake THEY made on my case…

And what mistake was that?

SAAD: The 10-year bar that I was never supposed to have by law.

Why were you never supposed to have a 10-year bar?

SAAD: A 10-year bar is only placed on someone who overstayed in the USA unlawfully for over 360 days starting at the age of 18. I was under ICE supervision since the age of 17 so I was never overstaying unlawfully. It was always with the permission of ICE. A three-year bar is only placed on someone who has overstayed unlawfully for over 180 days. The only overstaying I did was from November 24 to January 4 because I was detained. I was still 18 years old when I departed the USA.

And while you were detained you never got to consult a lawyer? But before they deported you, they said you had to sign the 10-year bar? It sounds like you were forced into an impossible situation. How do you take back a signature you should never have been forced to sign?

SAAD: No, I was not able to consult a lawyer nor given the ability to ask for one because they told me “if you refuse to sign any papers we give you, you will be criminally charged and kept in jail.”

Your case has attracted recent coverage from important international press such as the German magazine der Spiegel and the Calcutta newspaper The Telegraph. Your Official Group at Facebook in mid-August has about 5,000 friends who like it. What are the chances that The Saad will be able to high-jump over his 10-year bar?

THE SAAD: Everyone knows The Saad as someone who gets things done. A lot of people expect me home soon and even have things planned out for it. But what the public doesn’t know is that, even The Saad has his doubts about himself. We grow up in America knowing that “justice will prevail” so that’s what I hope happens. Someone will recognize this mistake and fix it.

[Greg Moses is editor of the Texas Civil Rights Review and author of Revolution of Conscience: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Philosophy of Nonviolence. He can be reached at gmosesx@gmail.com.]