|

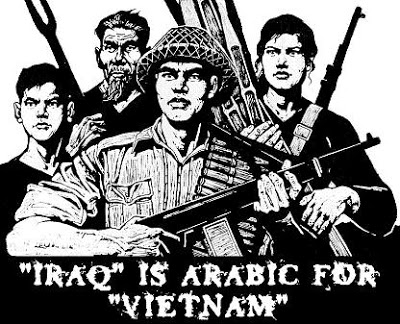

| Image from Democratic Underground. |

Cooperation over conflict:

We need to expand the ‘Iraq Syndrome’

As we reflect on the 10-year anniversary of the launching of the Iraq War, the madmen inside the beltway are talking about increasing U.S. military involvement abroad.

By Harry Targ | The Rag Blog | March 20, 2013

In a November/December 2005 Foreign Affairs article, “The Iraq Syndrome,” I argued that there would likely be growing skepticism about the notions that “the United States should take unilateral military action to correct situations or overthrow regimes it considers reprehensible but that present no immediate threat to it, that it can and should forcibly bring democracy to other nations not now so blessed, that it has the duty to rid the world of evil, that having by far the largest defense budget in the world is necessary and broadly beneficial, that international cooperation is of only very limited value, and that Europeans and other well-meaning foreigners are naive and decadent wimps.”

Most radically, I went on to suggest that the United States might “become more inclined to seek international cooperation, sometimes even showing signs of humility.”

— John Mueller, “The Iraq Syndrome Revisited,” Foreign Affairs, March 28, 2011

David Halberstam reported in his important book,The Best and the Brightest, that President Roosevelt directed his State Department to develop a position on what United States foreign policy toward Indochina should be after the World War in Asia was ended. Two choices were possible in 1945: support the Vietnamese national liberation movement that bore the brunt of struggle against Japanese occupation of Indochina or support the French plan to reoccupy the Indochinese states of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos.

As the Cold War escalated the United States rejected Ho Chi Minh’s plea for support for independence and began funding the French in their effort to reestablish colonialism in Indochina. When the French were defeated by the Viet Minh forces in 1954, the United States stepped in and fought a murderous war until the collapse of the U.S. South Vietnamese puppet regime in 1975.

Paralleling the struggle for power in Indochina, competing political forces emerged on the Korean Peninsula after the World War. With the Soviet Union and China supporting the North Koreans and the United States supporting a regime created by it in the South, a shooting war, a civil war, between Koreans ensued in 1950 and continued until an armistice was established in 1953. That armistice, not peace, continues to this day as a war of words and periodic provocations.

Political scientist John Mueller analyzed polling data concerning the support for U.S. military action in Korea and Vietnam, discovering that in both wars there was a steady and parallel decline in support for them. Working class Americans were the most opposed to both wars at every data point. Why? Because working class men and women were most likely to be drafted to fight and their loved ones the most likely to suffer the pain of soldiers coming home dead, scarred, or disabled.

Polling data from the period since the onset of the Iraq war followed the pattern Mueller found in reference to Korea and Vietnam. In all three cases levels of support for U.S. war-making declined as the length of the wars increased and casualties rose. The American people typically gave the presidents some flexibility when the wars started and the rally-round-the-flag phenomenon prevailed. But then resistance grew.

Throughout the period from the end of the Vietnam War until the 1990s, each presidential administration was faced with what foreign policy elites called “the Vietnam Syndrome.” This was a pejorative term these elites used to scornfully describe what they correctly believed would be the resistance to foreign military interventions that they periodically wished to initiate.

President Reagan wanted to invade El Salvador to save its dictatorship and to overthrow the Sandinista regime in Nicaragua. He would have preferred to send troops to Angola to defend the anti-communist forces of Jonas Savimbi of UNITA.

To overcome the resistance to launching what could become another Vietnam quagmire, policymakers had to engage in “low intensity conflict,” covert operations that would minimize what the American people could learn about what their government was doing and who it was supporting. Reagan did expand globally and sent troops to tiny Granada, but even Reagan’s globalism, militarism, and interventionism were somewhat constrained by the fear of public outrage.

President George Herbert Walker Bush launched a six-month campaign to convince the American people that military action was needed to force Iraqi troops out of Kuwait. Despite a weak endorsement of such action by the Congress, the American people supported Gulf War I because casualties were small and the war lasted only a month. During a press conference announcing the Gulf War’s end in February 1991, Bush proclaimed that “at last we licked the Vietnam Syndrome.”

Clinton knew better. He limited direct U.S. military action to supporting NATO bombing in the former Yugoslavia in 1995, bombed targets in Iraq in so-called “no-fly zones in 1998,” bombed Serbia in a defense of Kosovo in 1999, and used economic embargoes to weaken so-called “rogue states” throughout his eight years in office.

It was President George Walker Bush who launched long and devastating wars in Afghanistan in 2001 and Iraq in 2003. The Bush administration used the sorrow and anger of the American people after the 9/11 terrorist acts to lie, deceive, aggress, and qualitatively increase the development of a warfare state.

As Mueller has suggested, an “Iraq Syndrome” had surfaced by 2005 as the lies about that war became public, the war costs were headed toward trillions of dollars in expenditures, and troop deaths and disabilities escalated. And of course an historically repressive society, Iraq, was so destroyed that U.S. troops left it in shambles with hundreds of thousands dead, disabled, and in abject poverty.

As we reflect on the 10-year anniversary of the launching of the Iraq War in March 2003, the madmen inside the beltway are talking about increasing U.S. military involvement in Syria, not “taking any options off the table” in Iran, and threatening North Korea.

Meanwhile the United States is beefing up its military presence in the Pacific to “challenge” rising Chinese power, establishing AFRICOM to respond to “terrorism” on the African continent, and speaking with scorn about the leadership in Latin America of recently deceased Hugo Chavez.

The American people must escalate commitment to its “syndromes,” demanding in no uncertain terms an end to United States militarism. Mueller’s call for a U.S. foreign policy that emphasizes cooperation over conflict motivated by humility over arrogance is the least the country can do to begin the process of repairing the damage it has done to global society.

[Harry Targ is a professor of political science at Purdue University and is a member of the National Executive Committee of the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism. He lives in West Lafayette, Indiana, and blogs at Diary of a Heartland Radical. Read more of Harry Targ’s articles on The Rag Blog.]