What progressives need to know:

History is complicated

Though it’s darkest before the dawn

These thoughts keep us moving on…

By Harry Targ / The Rag Blog / October 20, 2010

I became a radical in the 1960s. I kept putting off being active until the late ’60s but I slowly involved myself in the anti-war movement. When I started teaching around this time I noticed that many students became instant radicals; 19 year-old- kids going from lack of political awareness to militancy in a matter of weeks.

The Southern movement was inspiring; young people and their elders were transforming the system of Jim Crow. College campuses were bursting with energy, demanding “student rights” and “relevant” courses. Then the anti-war mobilizations grew bigger and bigger. Each massive mobilization in D.C., in New York, in Chicago, in San Francisco challenged organizers to produce larger and larger crowds and for a time the crowds did get bigger.

Many of us began to see the achievement of peace and justice as just around the corner. We were on the verge of building a new world, not unlike the world of altruism and love envisioned by Che Guevara.

But then everything seemed to fall apart. The New Left split. African Americans sought to build their own movements. Women and gays began to argue that human liberation should be for them as well.

Nixon was elected. Vietnamization did not end the war but shifted the U.S. role from ground to massive air strikes across all of Vietnam. The Xmas bombing destroyed virtually all of North and South Vietnam. Black Panthers were targeted for assassination by the federal government and local authorities. Students were murdered at Kent State and Jackson State.

The youthful energy, the visions of socialism dissipated. Particularly the young became disillusioned. I remember one student telling me in the early 70s: “I tried the political thing and it didn’t work.”

The seeming victories of the ’60s and ’70s were followed by the brutal Reagan “low intensity” conflicts of the ’80s: leading to death and destruction in Nicaragua, El Salvador, Angola, Ethiopia, Cambodia, and Afghanistan. And Reagan trumpeted the shift from welfare state capitalism to neoliberal globalization: privatization, de-regulation, and shifting all human activities from the public sector to the market. Then the last large-scale check on the globalization of capitalism and imperialism, the Soviet Union, collapsed.

This brief history reflects my own intellectual immaturity. Along with hundreds of thousands of others I was caught up in the emotion of the times. Not informed about the subtleties and complexities of history, I assumed that the path to victory, the path to peace and justice, would be smooth and linear. I did not expect major setbacks. I assumed that once we demonstrated our passion, our ability to mobilize large numbers of people, then the job was done.

But as I read Marx, involved myself in the labor movement and Central American solidarity, I began to realize that history does not work in simple and linear ways. Struggle must continue. Those who oppose us will continue to defend their privileges and their position. Patience is as critical to our work as is passion. And, these lessons of history are more likely to be understood by workers, by marginalized peoples, by most of the citizens of the globe who may not have been the beneficiaries of the short-term victories of social movements.

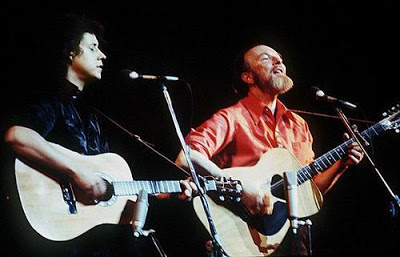

I also thought more about the lessons embedded in the music of my youth and the deep philosophical meaning of the simple verses of the songs of folk singers such as Woody Guthrie, and Pete Seeger and the Weavers.

I remember Woody’s son Arlo Guthrie describing his own connection to the progressive folk music tradition:

One of the great things that I learned from both my mother and my dad and from some of these folks here is that this kind of wanting to make the world a better place is not something that started with the Weavers….they recognized and continued a tradition that’s probably been going on for as long as people have been around. And that is a wonderful thing for a young person to discover; he or she is not the beginning of a thing but somewhere in the middle of a long line of people who are concerned about making the world a better place to be.

It gives you the ability to not get so anxiety-prone over what’s going on from moment to moment but to take a little longer look and know that you don’t have to finish a job within the span of a lifetime. All you have to do is link up to the future. That’s the job of being a human. It’s to make the connection to the future and hold on to the connection to the past

(Album notes from HARP, Redwood Records.)

In addition, I would often think about Pete Seeger singing in “Quite Early Morning” that it is “darkest before the dawn.”

Some say that humankind won’t long endure

But what makes them so doggone sure?

I know that you who hear my singing

Could make those freedom bells go ringing

I know that you who hear my singing

Could make those freedom bells go ringingAnd so keep on while we live

Until we have no, no more to give

And when these fingers can strum no longer

Hand the old banjo to young ones stronger

And when these fingers can strum no longer

Hand the old banjo to young ones strongerSo though it’s darkest before the dawn

These thoughts keep us moving on

Through all this world of joy and sorrow

We still can have singing tomorrows

Through all this world of joy and sorrow

We still can have singing tomorrows

So let’s get back to work.

[Harry Targ is a professor of political science at Purdue University who lives in West Lafayette, Indiana. He blogs at Diary of a Heartland Radical.]

Wow, I am so happy to see a modicum of reason creeping into your writings! This is the best column I can remember from all your writing. Happy I am that at last you are seeing the light as we both come to the end of the tunnel.

Nice Job Professor!