Let’s be frank:

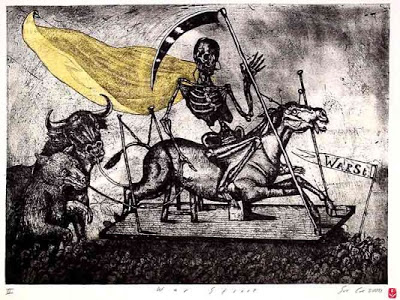

The United States has been

in perpetual war

With the onset of the Korean War, the politics of fear converged with the politics of empire.

By Harry Targ | The Rag Blog | December 27, 2011

Liberal cable commentators have been waxing eloquent about the withdrawal of the United States military from Iraq while ridiculing and scorning the recently deceased dictator of North Korea, Kim Jong Il. They fail to see the historic connections between the onset of war along the Korean peninsula in 1950 and the Iraq war of our own day.

If pundits reflected on the causes of the Korean War and the consequences following it they might see the culpability of the United States in launching a 60-year war system that has cost the lives of millions of people all across the Asian, Middle Eastern, African, and Latin American landscape.

To use the language of our own day, we need to “Occupy Our Minds,” or “Occupy Our History.” We need to understand where the North Korea of Kim Jong Il came from and why the United States created a dictator in Iraq, Saddam Hussein, and then destroyed him, his country, and hundreds of thousands of his people. This revisiting of the American past is painful but necessary.

Consider the Korean peninsula. It was a colony of expansionist Japan from the dawn of the twentieth century until the end of World War II. After that war, Korea was “temporarily” split at the 38th parallel by the United States and the former Soviet Union for “administrative purposes.” As the war ended, the Korean people fully expected to create their own independent state. “People’s Assemblies” were held throughout the peninsula to serve this purpose.

In the South, under U.S. control the assemblies were ignored. Over the next five years, using the new United Nations as the stamp of legitimacy the United States created an unpopular regime in the South led by Syngman Rhee. Rhee, tied to western anti-communist interests and domestic wealth very much like Chiang Kai Shek in China and later Ngo Dinh Diem in South Vietnam, established a brutal dictatorship. The Soviets, in the north, established a Communist regime led by Kim Il Sung.

In 1950 powerful foreign policy interests promoted a global U.S. foreign policy that would benefit from war. General Douglas McArthur, overseer of post-war Japan; John Foster Dulles, anti-communist foreign policy spokesperson of the Republican Party; and Rhee, on the verge of losing his power in South Korea, met in Tokyo in May. Conversation ensued that likely included making war on North Korea.

Back in Washington, Dean Acheson, Secretary of State, and his key aide, Paul Nitze, were lobbying for a new bold military policy, proclaimed in the secret National Security Document 68. It called for military spending to be the number one priority of each American administration. The reason, the document claimed, was the world-wide threat to civilization represented by international communism.

George Kennan’s “containment” policy, beefing up U.S. and allied forces to protect against any aggressive attack from a prospective enemy, was not enough. By 1954, the document predicted, the former Soviet Union would be as powerful as the United States.

As Acheson himself admitted in his memoirs, he felt the need to exaggerate the threat to United States security to gain support for a more global U.S. foreign policy. In other words, support for empire required lying to the American people. In the Korean case, an artificial division of the Korean peninsula, contestation between competing political forces, and a North Korean military attack on the South was reframed as a worldwide war on freedom and democracy. The Korean War institutionalized the big lie.

Then the Truman Administration, the Defense Department, big corporations, the major media, and many religious institutions launched a campaign of fear based on a fantasy of a dangerous communist subversion. Who could question a dramatic military response to a nation under siege.

With the onset of the Korean War, the politics of fear converged with the politics of empire. In sum, the United States redefined a civil war between Koreans, north and south of the 38th parallel, into a struggle between the “free world” and “international communism.”

The Korean War led to the deaths of 4 million Koreans and 54,000 U.S. soldiers. Between 1950 and 1995, the United States continued to develop the largest military force in the world, with hundreds of bases in 30 or more countries, dozens of covert military operations, and support for countless dictators in countries of the Global South. In wars in which the United States had a role during these 45 years, some 10 million people died, most of them civilians.

Fifty-three years after the onset of the Korean War, the United States launched a war on Iraq based on lies. The American people were told of the dangers the Iraqi regime posed for United States security. The threat was no longer communism but terrorists. And Saddam Hussein was framed as a supporter of terrorism against the West who possessed weapons of mass destruction.

These were lies based on significant historical distortions of the politics of the region. The details were different but the arguments for war on North Korea and the war on Iraq were both based on lies. The same case can be made for most U.S. interventions and wars from Korea to Iraq.

The policies of fear, empire, and military operations continued in the 21st century. The war in Afghanistan, begun in 2001, still goes on. We now celebrate the ostensible end of the Iraq war after nine years. About 10 thousand U.S. soldiers and probably a million Afghan and Iraqi people have died in these two wars. Economists predict that the Iraq war alone will have cost the U.S. government 3 trillion dollars by 2030, a total similar to U.S. military expenditures between 1945 and 1990.

So when pundits ridicule the dictatorship in North Korea and make grandiose statements about the millions imprisoned, killed, or starved, no mention is made about why the Korean War was launched, whose interests it served on the United States side, and how U.S. aggressiveness was used by North Korean political elites to justify dictatorship there.

And, the failures of the North Korean economy are presented as solely the result of their socialist economy, not the 60-year war and economic embargo on that country perpetrated by the world’s most powerful country.

Ironically, while media pundits condemn poor North Korea for constructing deliverable nuclear weapons, they fail to point out that countries defined as enemies of the United States, such as Iraq and Libya, were subject to U.S. military attack because they did not have such weapons to deter military assault.

The death of the current dictator of North Korea and the end of U.S. military operations in Iraq should encourage a frank and serious discussion about the United States foreign policy of perpetual war that has been a central feature of the U.S. role in the world since Korea. As masses of Americans mobilize in parks, reoccupy foreclosed homes, and in other ways petition government to change its ways, elimination of the system of constantly preparing for and engaging in war must be included in demands for change.

[Harry Targ is a professor of political science at Purdue University who lives in West Lafayette, Indiana. He blogs at Diary of a Heartland Radical — and that’s also the name of his new book which can be found at Lulu.com. Read more of Harry Targ’s articles on The Rag Blog.]