Take a deep breath:

How do we build our movements?

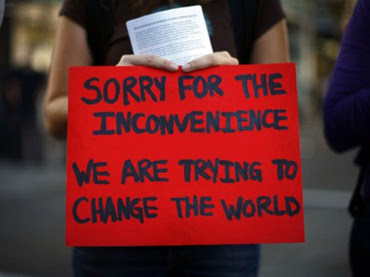

The response of 2011 was spontaneous, passionate, daring, and electric in its transformational possibilities.

By Harry Targ | The Rag Blog | April 25, 2012

Over the last 14 months we have observed Arab Spring, the Wisconsin uprising, labor ferment throughout the American Heartland, and the formation of Dream coalitions. In addition Occupy movements last fall spread like wildfire all across the country and with the arrival of spring are resuming.

Most recently anti-racist mobilizations have occurred in response to the execution of Troy Davis and the murder of Trayvon Martin.

In response, socialist and progressive organizations, single issue groups, political party activists, and visible pundits have called for or organized rallies, marches, conferences, and other mobilizations in Washington D.C., Chicago, New York, and elsewhere.

Grassroots activists, motivated by a passion for change, and sometimes a sense of desperation, are on the move.

While these are exciting times for progressives and lifetime organizers, it makes sense to take a deep breath, reflect on the concrete situations of struggle we face, and ask ourselves how best to channel (and preserve) our energies and resources.

Particularly, three questions need to be addressed and readdressed as political contexts change:

- How do we build our movements?

- What do we want to achieve?

- How do we decide what to do?

Building our movements

It still is the case that movements are built out of a complicated array of forms of activism. Obviously there are no easy answers or mathematical formulae but several tools are regularly used in our work.

First, education, propaganda, calls to action, and programmatic visions are communicated through the innovative use of various media. Print publications such as newspapers, pamphlets, books, and flyers have been staples of organizers since the printing press was invented. There are some communities, including my own, in which progressive newspapers are printed regularly and distributed.

Various progressive presses, such as Changemaker, have published books and edited materials not readily available to the left reading public. In some communities alternative radio and television programs tell the story of activism on a regular basis. I know of regular progressive radio shows in West Virginia, Indiana, Wisconsin, Texas, and Oregon.

And, of course, 21st century electronics have added a broad array of blogs, listservs, Facebook and websites to the tool kit of radical communication. For all its flaws, and there are many, the Internet has dramatically democratized and made cheaper the ability to communicate messages near and far.

Second, political events provide a way of communicating to and educating audiences of potential activists. In virtually every community where progressive politics is alive and well, groups sponsor public lectures, films, concerts, and picnics and other social gatherings. The idea is to bring people together to listen and talk about key issues, hoping that such activities will recruit new members

Third, activists organize rallies, marches, sit-ins, leafleting campaigns, petition drives, and other public actions that are designed to educate and mobilize activists at the same time. These actions can make the movements more visible, if they receive media attention, and, at least, catch the eye of passersby who are concerned about the issues raised and have not yet committed to organized work to bring about change.

Fourth, organizers generally believe that the most effective but yet the most demanding work involves interpersonal interactions: door to door campaigns, tabling at public events, organizing study groups, and holding meetings that address substantive issues as well as organizational business.

Obviously, each of these forms of activism is vital to the construction of progressive groups and mass movements and if we reflect on the work that we do, all of the four forms are used. In addition, the first three forms can occur at regional or national levels as well as in local communities. The fourth, however, requires work in face-to-face communities, or in what we call the grassroots.

What do we want to achieve?

Most progressive movements are motivated by a variety of goals. Of necessity, most of the goals are short or medium range, while in the end most progressives and/or socialists are committed to the construction of a humane, democratic, and socialist society; one in which the basic needs and wants of every person are met.

Progressives want to educate. That is, they want to communicate and convince a large group of people that particular policies and the general vision of a more humane society are desirable and achievable.

Education involves presenting a compelling analysis of the nature and reasons societies are failing to meet the needs of the people, presenting an alternative vision of society that can meet peoples’ needs, and offering some explanation as to how we can move from here to there.

Progressives want to mobilize large numbers of people to their cause. The forces of reaction have vast economic resources, are positioned in the apex of powerful political and economic institutions, and oftentimes have access to the repressive apparatuses of the state. Social movements throughout history have been effective to the extent that they have been able to assemble their one potential resource, large numbers of people.

While “people power” is a slogan, it also is a fact. Again, from Tahrir Square, to Madison, Wisconsin, to Occupy Wall Street, it has been large numbers of loud, militant, and angry people who have forced their resistance on the public stage.

Progressives want to use people power to deliver demands to those who administer the state. The wealthy and powerful can communicate their wishes to policymakers in the corridors of power. The people can communicate primarily by delivering demands.

While small groups of progressives have been able to make their demands visible through bold actions that find their way sometimes into the media, we have learned over and over again that masses of people, delivering demands, have a greater likelihood of being heard and mobilizing others to the cause.

Many progressives believe that electoral work remains a powerful tool for educating, mobilizing, delivering demands and, on occasion, successfully transforming their passions into policies. In a society like our own in which “politics” is defined by most people as elections, progressives need to engage in that arena (along with other venues).

It is because of elections that activists can knock on doors, talk about single payer health care, convince people that wars in Afghanistan and other places are ill-advised, and communicate to people that the rights of workers, women, and people of color must be protected.

All of these goals require raising money and signing up new members. Organization building is both a goal and a means to achieve other goals. One of the enduring dilemmas for today’s progressives is that on the one hand vast majorities of people support progressive change when asked but only tiny minorities step forward to work to create that change.

Further, there are traditions among political activists that claim that organization-building is antithetical to political change. And, many of those who are readily available to protest, sit-in, and generally raise hell are resistant to attending meetings, debating strategy and tactics, entering names of new members on computer lists, and all the other necessities of organization building that are frankly boring.

In certain circumstances, progressives feel a need to bring institutions to a halt. Tactics such as the strike, the occupation, and the work slowdown take on a life of their own as activists seek to bring the institutions of oppression and exploitation to a halt, at least for a time.

Such actions are themselves a goal and a tool for achieving other goals. In each of the path-breaking campaigns listed at the outset, dramatic actions stimulated the creation of mass movements. Oftentimes the actions themselves spark the construction of movements for fundamental change.

Finally, some progressives have acted on the belief that alternative institutions can and should be built within the old order. Progressives learn by doing, engage in trial and error institution-building, and provide visible models for those who have not yet joined the movement. Sometimes the alternative institutions fulfill a need irrespective of the effectiveness the alternatives served in building a mass movement.

Deciding what to do

This is the perhaps the most difficult issue to address. The year 2011 was an extraordinary time in social movement history. After a long drought in America (and perhaps around the world) masses of workers, women, people of color, youth, the elderly, and people from faith communities stood up and said “no” to dictatorship, attacks on workers’ rights, the war on women, violent racism, and further destruction of the air, water, and natural landscape.

The magnitude of the uprisings probably matches the thirties or the sixties in the United States. Paradoxically, despite the long years of grassroots activism and important work done by national organizations, progressives were caught by surprise.

As a result of the shock waves of 2011 we should reflect upon the issues that need to be addressed, prioritizing work on them based on available resources. Progressives should make decisions about prioritizing short and/or long term policy and structural changes and the question of the location of venues for action at given times.

For some (I am one) politics begins at the base; that is in the communities in which activists are located. For others, coalition building at the national level must be prioritized.

What seems clear is that the forces of reaction in the United States and elsewhere are organized. They have enormous resources. They have been planning for a long time to reconstruct economic and political institutions to shift power and wealth back to the few.

Since the 1980s at least ruling elites have sought to return America to the “gilded age,” the post-civil war era when bankers and speculators ruled America without cumbersome government provisions of some rights and resources to the vast majority of people.

The response of 2011 was spontaneous, passionate, daring, and electric in its transformational possibilities. But now, progressives need to reflect on where we are, what our resources are, how to use them effectively, what priorities in action need to be developed, and how we might most effectively empower people.

Spontaneity and reflection represent two dimensions of a successful social movement. One alone will not create the kind of humane society most of us are working to achieve.

[Harry Targ is a professor of political science at Purdue University who lives in West Lafayette, Indiana. He blogs at Diary of a Heartland Radical — and that’s also the name of his new book which can be found at Lulu.com. Read more of Harry Targ’s articles on The Rag Blog.]

“In addition Occupy movements last fall spread like wildfire all across the country and with the arrival of spring are resuming.”

The only people flocking to the occupy movements were those who already were progressives or even farther to the left. To the vast majority of Americans, they were a group that needed a job and a bath. The fact that they had weeks and months to camp out was enough to define them pretty clearly. Other than a catch phrase that was quickly usurped by the political class, their impact, especially on politics, has been nil. If you are hanging your hat on that grou .. good luck.

– Extremist2TheDHS