Words still matter:

Speeches that speak to our times

By Harry Targ / The Rag Blog / January 3, 2011

This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence — economic, political, even spiritual — is felt in every city, every State house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society.

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military/industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes…

Today, the solitary inventor, tinkering in his shop, has been overshadowed by task forces of scientists in laboratories and testing fields. In the same fashion, the free university historically the fountainhead of free ideas and scientific discovery, has experienced a revolution in the conduct of research… a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity…

The prospect of domination of the nation’s scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present and is gravely to be regarded.

Yet, in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific/technological elite.

— Dwight D. Eisenhower, January 17, 1961

Words still matter

We have become so drugged by politicians that we often fail to reflect on the power of their words. Seeing books on library shelves with titles like “Speeches of Great Americans” culls up in our minds Readers Digest, the History Channel, Sunday morning sermons, and all the crap that passes for political discourse in the 21st century. Even profound speeches, and the lives of profound political actors, are transformed, debased and normalized, such that the power of words or deeds becomes acceptable to ruling classes and even made to have commercial value.

Every once in a while though a politician or activist says something that is rich with theoretical insight and inspiration and begs for action. The power of the words cannot be demeaned, delegitimized, or made palatable to all. And, it behooves progressives to revisit those words and use them for practical political work.

The Military/Industrial Complex

When President Eisenhower gave his final address to the nation on January 17, 1961, 50 years ago, he warned of “the acquisition of unwarranted influence” of a military/industrial complex. He originally included the word “academic” but later eliminated it, probably for reasons of length. He was alerting Americans to the breadth and scope of military power over the world and American society.

The President’s words constituted a shocking challenge to the soon-to-be Kennedy era defense intellectuals who criticized the outgoing president’s reluctance to spend even more than the $40 billion he invested on the military. Even his direct orders to subordinates to overthrow Guatemala’s President Jacob Arbenz and Iran’s Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh and his declaration of the Middle East as a free-world sanctuary was not enough for the 1960s theorists and practitioners of “modernization,” “development,” and “democracy.”

Although Eisenhower warned us of the impacts of the military/industrial complex, he could not foresee the magnitude of the controls on America’s public life that soon resulted.

First, he only dimly saw the changes that would occur in the techniques of empire. CIA money ensured election outcomes in other countries. American intelligence and military forces engineered brutal military coups. Military advisors revamped armies and repressive police forces in countries threatened by revolutionary change. The United States used “low intensity conflict” to train anti-government reactionaries.

And then to mollify domestic critics, the U.S. initiated the privatization and outsourcing of the military as an adjunct to the over 700 U.S. military bases in more than 40 countries. Most recently, high tech weapons, unmanned aerial vehicles, are used to kill people without endangering U.S. soldiers. Technological advances and the globalization of U.S. violence continue.

Eisenhower was inalterably opposed to the militarization of the U.S. economy. While he was willing to allot $40 billion in 1950s currency, he resisted the demands from Beltway liberals and defense contractors to double military spending. By the 1960s, half of the federal budget began to go to the military and one in 10 workers derived wages from defense contracts. And that continues, but with less public criticism.

Finally, Eisenhower spoke to the militarization of American culture. The university became a research arm of the complex. Students were taught about the virtues of military “readiness,” “the communist threat,” the problem of “human nature” and perpetual war, and, more recently, the endless danger of “terrorism.”

Virtually every large corporation, producing such products as toothpaste, toys, breakfast cereal, medications, automobiles, electronics, or energy, is steeped in military contracts. The public airwaves, the internet, movies, and sports are laced with war, violence, killing, and competition. As Eisenhower put it: “Our toil, resources, and livelihood are all involved: so is the very structure of our society.”

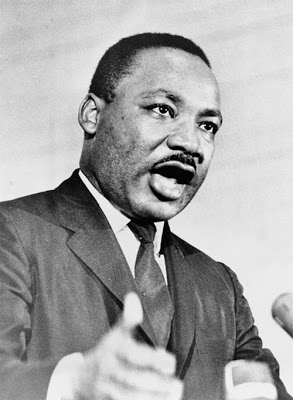

Somehow this madness must cease. We must stop now. I speak for those whose land is being laid waste, whose homes are being destroyed, whose culture is being subverted. I speak for the poor of America who are paying the double price of smashed hopes at home and death and corruption in Vietnam. I speak as a citizen of the world, for the world as it stands aghast at the path we have taken

— Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., April 4, 1967

Making war overseas and advancing hunger at home

In April, 1967 Dr. Martin Luther King spoke at Riverside Church in New York City and made it crystal clear that wars elsewhere not only kill the designated enemies, but impoverish poor working people at home. Dr. King made a critical contribution to the discussion of the link between war and foreign policy and people’s lives. Killing in other lands is an immoral abomination. While that needs to be critically understood, the unequal distribution of wealth and income within the United States is stark and is intimately connected to foreign adventures. And, in fact, the more resources that are allocated for killing others, the less there are to serve the needs of those at home.

President Lyndon Johnson, who increased the U.S. troop commitment from 16,000 in 1963 to 540,000 in 1968 and who launched daily bombing of targets in North and South Vietnam in 1965 that went unabated until 1968 tried to create a “war” on poverty at home. Dr. King knew that this country could not do both: that there was an inverse relationship between war-making and domestic prosperity. As he put it: “I speak for the poor of America who are paying the double price of smashed hopes at home and death and corruption in Vietnam.”

And as the years unfolded and the United States shifted from a military draft to a volunteer army, there was an increase in the percentage of those who could not find jobs and earn a decent income and became the foot soldiers for future wars.

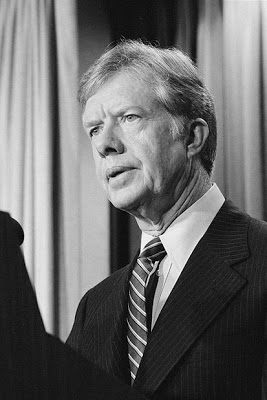

In a nation that was proud of hard work, strong families, close-knit communities, and our faith in God, too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption. Human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns. But we’ve discovered that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning. We’ve learned that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or purpose.

What you see too often in Washington and elsewhere around the country is a system of government that seems incapable of action. You see a Congress twisted and pulled in every direction by hundreds of well-financed and powerful special interests. You see every extreme position defended to the last vote, almost to the last breath by one unyielding group or another. You often see a balanced and a fair approach that demands sacrifice, a little sacrifice from everyone, abandoned like an orphan without support and without friends.

— Jimmy Carter, July 15, 1979

Corporate/financial elites and the creation of self-indulgence

Perhaps the least known of the prophetic speeches cited here is the one presented on television in July, 1979 by President Jimmy Carter. He was called to speak about the growing energy crisis, dramatic increases in the price of oil, growing dependency on foreign oil, concentrated economic power in Washington, and the celebration of a culture of self-indulgence, consumerism, materialism, and competition.

While this speech did not address foreign and military policy as directly as the other two, it warned the American people about the dangers of war, foreign dependency on oil, and an international system driven by oil giants and oil-rich countries. He linked these to a domestic culture that defined its success on the basis of how much it could consume.

President Carter challenged the basic precept of the corporate culture that evolved out of industrial and monopoly capitalism in the twentieth century; its basic paucity of meaning and purpose. “But we’ve discovered that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning. We’ve learned that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or purpose.”

What can we learn from these famous speeches?

We should bring to our political work the idea that words still matter. In addition, we must reflect upon the possibility that mainstream politicians, presidents for example, may say things that should and could be appropriated to build a progressive agenda. And, perhaps more difficult, we need to cut through the propaganda which often leads political figures to be lionized and thus transformed into everyday icons.

Dr. King was a radical, against racism, sexism, and classism. He opposed war. He saw the vital interconnections between massive governmental waste and human suffering. And he saw that the direction U.S. society was heading in was pure “madness.”

Substantively, we should revisit these speeches to raise again our opposition to war and empire and military spending. We need to stand with our brothers and sisters who are demanding jobs and justice. And we must stand with those, whether secular or religious, who argue against a self-indulgent, consumption-based and competitive society.

[Harry Targ is a professor of political science at Purdue University who lives in West Lafayette, Indiana. He blogs at Diary of a Heartland Radical.]