Colombia and the School of the Americas:

A history of human rights abuse

By Marion Delgado / The Rag Blog / December 3, 2009

See ‘Know your new military bases,’ a look at Tolemaida Air Base in Melgar, Below.

CARTAGENA DE INDIES, Colombia —

The United States recognized Colombia’s Military Forces on Friday, November 6, 2009 for their effort and commitment towards Human Rights causes in the country.

According to the U.S. Institute for Hemispheric Security Cooperation, the Colombian Army stood out as unique in the world with regard to its Human Rights leadership and the fact that it has human rights offices[sic] in its divisions, brigades and battalions.

This was reported on Colombian President Alvaro Uribe’s website. I ran across it while researching the Colombian Army’s (COLAR) record on Human Rights. From the research I’d already done at that point, it gave me pause… WTF?? I wondered, “Who would give COLAR a human rights award?”

Well, it came as no surprise when I finally figured out that the real name of the awarding organization was Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation. You will remember them as our old friends the School of the Americas, who have long been associated with Human Rights issues.

The posting went on:

Lt Colonel Javier Alberto Ayala Amaya was awarded the medal of Commander of the U.S. Army, for his meritorious service and outstanding professionalism as an instructor in the field of Human Rights.

In addition, the rules of behaviour in combat and confrontation employed by the Army reflect the experience of the troops in operational law, which places the institution as a hemispheric leader in education and training programs.

Lt Colonel Amaya is part of a large group of Colombia officers and civilians who educate on human rights abroad.

I searched 14 reference sources for any mention of the “Commander of the U.S. Army Medal.” Nada. I found a “U.S. Army Commander’s Medal” that is awarded to civilians, but no mention of awarding that to foreign military personal. Probably something they hammered out just before the ceremony. It became apparent that it was just another stick in a propaganda framework as part of making our co-conspirators in the new US/Colombia military pact seem friendly. But, COLAR and the School of the Americas (SOA) do have a long association.

How the SOA shelters soldiers who face trial at home

One of the apparent functions of SOA is post-graduate protection of the thugs they train and turn loose on the population of Colombia.

In 1992, Lieutenant Colonel Victor Bernal Castaño was enrolled at the SOA to avoid having to answer to investigators about the Fusagasugá massacre of a peasant family, according to the Colombian legislature. The SOA enrolled him in its longest and most prestigious course, the Command and General Staff College, and made him “Jefe del Curso,” (Chief of Course). This was after he had already been implicated in the 1989 disappearance of campesina Sandra Velez, and was known to protect and aid death squads. Sandra is just one of hundreds who met the same fate, listed on the site below.

In another example from the early 1990s, Lieutenant Colonel Luis Felipe Becerra Bohórquez attended the SOA while a warrant was out for his arrest for his leading role in the 1988 massacre of 20 banana workers in the Urabá region. The SOA claims Becerra Bohórquez was never “formally enrolled” in officer training there, but according to Colombian government records, the Colombian Army sent him to the SOA to avoid arrest. In 1993, after his extended shelter at the SOA, he returned to Colombia and led another massacre, this time murdering 13 civilians at Riofrío. In November 1993, under intense international pressure, Colombia dismissed Becerra from the military.

This is a long-standing role of the SOA. For instance, in 1982 First Lieutenant German Espinoza Rubio, who had already graduated from the SOA in 1976, faced with an investigation into his role in assassinating several campesinos, was spirited away to the SOA for a course in “Patrol Operations.” When the danger of the truth had passed he promptly “dropped” the course and returned home.

If you are thirsty for more atrocities by SOA graduates perpetrated on the Colombian people, there are plenty here.

The phony ‘War on Drugs’

The U.S. pays SOA graduates to murder civilians, lying to the public that the aid goes to the “War on Drugs”

In 1991, two Colombian generals thanked the U.S. Congress for $40.3 million in “anti-narcotics aid,” which they said would be used (illegally) in counterinsurgency campaigns in northeastern Colombia, where narcotics are neither grown nor processed. Both are members of the SOA “Hall of Fame”: General José Nelson Mejia Henao, inducted in 1989, and General Luis Eduardo Roca Malchel, inducted in 1991 after being known for war crimes, including torture, as recently as June 1988.

Prison guards trained at the SOA close their eyes while drug kingpins walk out of jail. In August, 1992, three Army officers were forced into early retirement after notorious cartel leader Pablo Escobar “escaped” from prison, where he had been living in grand style. Two officers were SOA graduates: Lieutenant Colonel Manuel José Espitia Sotelo, commander of the military police battalion guarding the prison, had graduated only months before. General Gustavo Pardo Ariza, head of the Fourth Brigade in Medellin, commanded soldiers who were supposed to be guarding the prison from which Escobar literally walked away.

On November 22, 1994, five top officers were dismissed by President Ernesto Samper, who overhauled the military leadership in the hopes of decreasing corruption and drug trafficking in the armed forces and improving the human rights record of the military. At least three were generals who graduated from the SOA and one is a member of the School’s “Hall of Fame,” inducted in 1993: General Hernán José Guzmán Rodriguez, Commander of the Colombian Army, known to protect and aid paramilitary death squads between 1987 and 1990, and before that known to command the soldiers who detained, tortured, gang-raped, and executed an innocent woman, Yolanda Acevedo Carvajal, and then concocted a story that she committed suicide by shooting herself in the nape of the neck.

The phony ‘War on Guerrillas’

On July 24, 1997, SOA graduate and guest instructor General Harold Bedoya Pizarro was fired from his position as chief of the armed forces by President Samper. Defense Minister Gilberto Echeverri suggested the dismissal is because of Bedoya’s unwillingness to commit to improving the military’s poor human rights record,

“Throughout Bedoya’s entire career [1965 to the present], he has been implicated with the sponsorship and organization of a network of paramilitary organizations. Bedoya, who has never undergone any investigation for his involvement in the massacres of non-combatants or other dirty-war crimes, is an articulate proponent of the continued legal involvement of local populations in counterinsurgency operations.”

On February 12, 1992, SOA graduate Captain Gilberto lbarra forced 3 peasant children to walk in front of his patrol to detonate mines and spring ambushes. Two were killed; one was seriously wounded.

From 1988-1991, at least 107 citizens of the village of Trujillo were tortured and murdered. An eyewitness said Major Alirio Antonio Urueña Jaramillo (an SOA graduate) tortured prisoners (including elderly women) with water hoses, stuffed them into coffee sacks, and chopped them to pieces with a chainsaw. The eyewitness soon disappeared. Major Urueña was promoted to Colonel. After intense international outcry, Urueña was dismissed from the Army in February 1995.

Also implicated in the Trujillo chainsaw massacre was SOA graduate Colonel Roberto Hernández, who during the same period (1990) supervised the illegal detention and torture of 42 people, most of them union members and human rights workers. Throughout the 1980s, Hernández was implicated in numerous extreme-right death squad activities.

In 1990, SOA graduate First Lieutenant Pedro Nei Acosta Gaiviso ordered the massacre of 11 campesinos, had his men dress the corpses like guerrilla forces, and then dismissed the killings as an armed confrontation between the Army and guerrillas.

And the beat goes on…

“That’s history,” you may say. In about an hour, using various sources, I turned up 17 pages of these horror stories. What about today, what kind of army will our troops mix with at the 10 Colombian military bases we’ll be sharing? What will they learn and take part in?

For one thing, they will be immediately used in Plan Patriota, in which some U.S. servicemen and women and civilian “advisors” are already involved.

Plan Patriota: Don’t ask — don’t tell

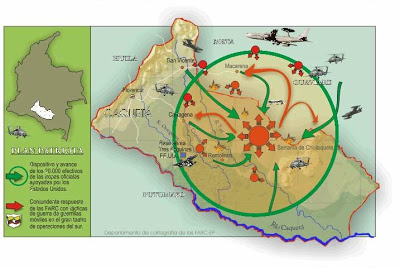

Shrouded in silence in Colombia, Plan Patriota has begun to emerge as the most ambitious military offensive to date against leftist guerrillas, with the U.S. military providing tactical and logistical support.

Taking part in the operation, which according to press reports involves 17,000 soldiers deployed in southern Colombia, are mobile forces and special jungle commandos trained by U.S. advisers and backed up by modern technology from the U.S.

The offensive is being carried out in a vast territory under the control of Colombia’s main rebel group, the 18,000-strong Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), which rose up in arms four decades ago.

Plan Patriota signals the entrance of the U.S. into a new, more intense phase of military involvement in Colombia’s internal armed conflict. Unlike Plan Colombia — also financed by Washington — Plan Patriota makes no pretense of furthering U.S. counter-drug objectives.

Instead, Plan Patriota underscores the potential for escalation beyond the mission understood by Congress and beyond the appetite of the American public, unlike its predecessor, Plan Colombia; this strategy has no stated humanitarian component.

Plan Colombia, which many observers have declared a failure, sought to reduce the supply of drugs to the United States — the world’s largest market for illegal drugs — by attacking production of coca and the jungle labs that convert the leaves into cocaine, a strategy that was simultaneously supposed to reduce revenues of the leftist insurgents.

Latin American Human Rights Association (ALDHU) warns of the impact of Plan Patriota on Ecuador, which shares a 640-km (398 mi.) border with Colombia, cautioning that it could lead to an increased flow across the border of Colombian civilians fleeing the conflict, and push drug and arms traffickers into Ecuador as well.

Plan Patriota is seen as complementary to the U.S. Andean Regional Initiative, focused on Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia and Panama, and aimed, among other things, at beefing up control along the borders with Venezuela.

General James Hill, until quite recently in charge of the U.S. Southern Command, confirmed what Colombian authorities have not admitted: the magnitude and extent of the offensive against FARC. Hill, who since November, 2008, has held 13 meetings with Colombian military officers and visited Ecuador six times, passed through Bogotá on June 23, 2009 ,after touring Larandia military base in the southern state (Departamento) of Caquetá, where Plan Patriota is coordinated.

The general praised the progress of the offensive that, as has now been revealed, began in June 2003 with an attack on rural areas south of Bogotá, where local peasants support FARC. He said that the U.S. military is providing Colombian armed forces with fuel, logistical support, and planning.

(General Hill was recently replaced by Four Star Air Force General Douglas Fraser who is now the Commanding Officer of SOUCOM. SOUCOM covers 45 nations and territories and the 16 million square mile Caribbean Sea.)

A spokesman from the Bolivarian Movement, FARC’s clandestine political arm, declares that despite the impressive U.S. technology, “the popular resistance remains unbeatable.”

According to a source who spoke on condition of anonymity, the ceiling set by the U.S. Congress on the number of military advisers has already been far surpassed. He said there are “around 2,000 U.S. mercenaries. People recognize them by their accent… They walk around the town of Cartagena del Chairá [in Caquetá], and are very heavily protected.”

Why the official secrecy about the biggest military offensive in the history of Colombia’s conflict? Consider U.S. operations in Iraq, where reporters from nearly all outlets — even Al Jazeera, to some extent — have been embedded with U.S. military units, often resulting in unabashedly supportive media coverage of that controversial war.

By most accounts, the reluctance to share information about Plan Patriota comes from the Colombian side. The Colombian military is highly reluctant to grant journalists or outside observers any interviews, access to installations, or entry into theaters of operations. The most-stated reason: the need to keep sensitive tactical information from reaching the enemy (FARC).

The more likely reason is nationalist sensitivity. Not only is the Colombian government likely to balk at the prospect of foreign reporters sticking their noses into Plan Patriota, they’re probably unwilling to make public the degree of U.S. participation in what they would prefer be considered a 100 percent Colombian offensive.

No matter what the reason, such secrecy is a mistake. It leads to fear that things are going worse than they may in fact be going. It gives credence to reports that as many as 1000 Colombian soldiers have been killed, that they are bogged down in the bush and suffering from flesh-eating diseases, that they have done little more than capture relatively low-ranking guerrillas and take over already-abandoned encampments, that morale is low, and that military operations are accompanied by almost no social investment in the long-neglected rebel zones.

This is fast becoming the mainstream view of Plan Patriota among the Colombian people and in the foreign press such as the Miami Herald — a big, costly military effort that has yielded few results. Is this perception correct? ¿Quién sabes? The only way we’ll find out is if the U.S. and Colombian governments stop neglecting public opinion and abandon their insistence on total secrecy.

The U.S. has already put $700 million into Plan Patriota (no wonder we can’t afford health care), and now it plans to put thousands of U.S. troops in also, as a part of the Andean Regional Initiative.

For a preview of what Plan Patriota will look like on the ground, take a look at reports on terror in Arauca from the Colombia Support Network. For the full story of what happened there go here.

Army killings of civilians

In recent years there has been a substantial rise in extrajudicial killings of civilians attributed to the Colombian Army, documented by the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, many human rights organizations, and, most recently, the UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Executions. Army members, under pressure to show results, take civilians from their homes or workplaces, kill them, and then garb them as combatants killed in action to increase their body count.

The alleged executions have been occurring throughout the country and involve multiple army brigades. The Attorney General’s Office is reported to be investigating more than 1,000 such cases involving more than 1,700 victims.

President Uribe for years publicly denied the problem existed, and accused human rights groups reporting these killings of helping the guerrillas in a campaign to discredit the military. After a major media scandal in September 2008 over the executions of several young men from Soacha, a low-income neighborhood of Bogotá, Uribe dismissed 27 members of the military, including three generals. There have been several more dismissals since then. But Uribe continues to claim these are isolated cases, emphasizing that there are only “22 proven cases” and charging that there are hundreds of “false allegations.”

Army Commander Mario Montoya, the subject of allegations linking him to abuses and paramilitaries, resigned in November 2008 right after the Soacha scandal. Uribe appointed him as ambassador to the Dominican Republic. Montoya’s replacement and reported protégé, General Oscar Gonzalez Pena, commanded the 4th Brigade of the Army when it had one of the worst records of extrajudicial executions in the country.

The UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Executions visited Colombia in June 2009. In preliminary findings, he noted that, “the sheer number of cases, their geographic spread, and the diversity of military units implicated, indicate that these killings were carried out in a more or less systematic fashion by significant elements within the military.” He pointed out that the Colombian military justice system contributes to the problem by obstructing the transfer of human rights cases to the ordinary justice system. His final report will address these and other issues, including possible incentives to members of the military that contribute to the killings.

The executions, which the Special Rapporteur described as “cold-blooded, premeditated murder of innocent civilians for profit, stand out as one of the most serious abusive practices by state agents we have documented in Latin America in recent years.” The frequency of the executions and the failure of President Uribe to acknowledge the gravity and scope of the problem, or to institute adequate measures to prevent it, should raise questions about the purposes for which U.S. military aid is being used, and the effectiveness of continued aid. That finding is just five months old.

Aww, shit. That’s it for this week. I can only write about Human Rights Abuse for so long before it begins to wear on my mind. I could go on for another 100 pages but I doubt that you could stand it long enough to read it.

This is a small window on the situation and the people U.S. troops will be in cahoots with as we go forward with the seven new bases the Obama government has signed on to pay for, construct, and occupy.

Next week I will take a look at corruption in the Colombian Military. Maybe I won’t find any. Whadda ya think?

Asi es en Colombia hoy

Know your new military bases

Melgar is a Colombian town in the Department of Tolima 65 mi. southwest of Bogotá and one hour north of Ibague the capital city of Tolima.

Melgar is located in the Sumapaz River Valley and borders the Department of Cundinamarca and Sumapaz River to the north, town of Icononzo to the east, and the towns of Cunday at the south and Carmen de Apicala to the west.

The town is home to a major military base called Tolemaida Air Base.

Tolemaida Military Fort, in the Nilo région; is at an elevation of 1,617 feet (493 m) above mean sea level, with two runways; 04/22 has an asphalt pavement measuring 9,280 by 96 feet and 04L/22R with a concrete surface measuring 1,431 by 65 feet.

Tolemaida is half way between Bogotá and Medellin. It has taken on a reputation as Colombia’s Abu Ghraib.

The Bogotá daily El Espectador reported on January 8, 2009, that in October, 2008, U.S. military officers and private contractors had overseen a session at the base in which three young girls from a nearby village were tortured and raped.

The sessions were apparently videotaped, and the tapes then distributed in the local village of Melgar, where the girls were from. They were subsequently ostracized and forced to flee the village with their families.

The most disturbing thing about the allegations is that the girls were not even suspected of anything; they had been lured to the base in exchange for money and a promise of visas to enter the U.S., and apparently used in a torture demonstration.

Your tax dollars

As at Larandia and Palanquero there are thousands of troops of all kinds at Tolemaida and Melgar, those listed below are the ones we know of that directly receive U.S. tax dollars from the Department of State and/or the Pentagon.

COLAR Lancero School (ESLAN)

COLAR Professional Soldier School (ESPRO)Rural Special Forces Brigade (BRFER)

- 2nd Special Forces BN (BFER1)

- 2nd Special Forces BN (BFER2)

- 3rd Special Forces BN (BFER3)

- 4th Special Forces BN (BFER4)

Rapid Deployment Force (FUDRA)

1st Mobile Brigade (BRM01)

- 19th Counter Guerrilla BN (BCG19)

- 20th Counter Guerrilla BN (BCG20)

- 21st Counter Guerrilla BN (BCG21)

- 22nd Counter Guerrilla BN (BCG22)

- 22nd Support and Services Company (CPS22)

2nd Mobile Brigade (BRM02)

- 15th Counter Guerrilla BN (BCG15)

- 16th Counter Guerrilla BN (BCG16)

- 17th Counter Guerrilla BN (BCG17)

- 18th Counter Guerrilla BN (BCG18)

- 23rd Support and Services Company (CPS23)

3rd Mobile Brigade (BRM03)

- 51st Counter Guerrilla BN (BCG51)

- 52nd Counter Guerrilla BN (BCG52)

- 53rd Counter Guerrilla BN (BCG53)

- 54th Counter Guerrilla BN (BCG54)

- 25th Support and Services Company (CPS25)

Instruction BN Army Aviation School (CERTA)

4th Air Combat Command (CACOM 4)

- For previous articles by Marion Delgado about the U.S. military presence in Columbia, go here.

Elsewhere in the blog there's discussion of whether or not Afghanistan is like Vietnam.

These articles are making it real clear what the similarities are between Vietnam and Colombia, especially the open admission that FARC cannot be defeated, and is in fact a popular insurgency.