Bring on your wrecking ball:

The politics of Bruce Springsteen

Springsteen’s patriotism is a central part of his being. He describes it as an ‘angry sort of patriotism,’ something that he doesn’t want to cede to ‘the Right side of the street.’

By Huw Beynon and Steve Davies / Red Pepper / October 12, 2012

LONDON — On a cold, wet day towards the end of June, Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band followed their eight pantechnicons into Manchester. They were there for the 39th leg of their North American and European tour, promoting Springsteen’s latest album Wrecking Ball.

After monsoon conditions all day, the rain stopped as the band took the stage of the Etihad stadium. This was the beginning of the great Bruce Springsteen show, part concert, part revivalist meeting, filled with theatricality and a fair amount of humoUr and pathos. The E Street big band sound provided a powerful backing to the lyrics of the 30 songs that filled the next three and a half hours.

At the start of the European tour, Springsteen explained how his deepest motivation “comes out of the house that I grew up in and the circumstances that were set up there, which is mirrored around the United States with the level of unemployment we have right now.”

In that house in Freehold, New Jersey, Springsteen’s father worked intermittently at the Karagheusian Rug Mill (which left him partially deaf), the local bus garage and for a while at the county jail. Unemployment was frequent, however, and it destroyed his confidence and sense of worth, leaving his wife as the organizer of the family home.

This tension between bad work and no work has been a perennial theme in Springsteen’s writing, alongside a search for freedom and self-discovery. It also left him with a strong attachment to places and the memories stored up in them.

When the Giants’ stadium in New Jersey was up for demolition, he sang the first version of “Wrecking Ball” at a farewell concert, developing the physical process of destruction into a brilliant metaphor of class violence and the “flat destruction of some American ideals and values.” He sings of how “all our little victories and glories/ Have turned into parking lots.” And he repeats the invocation: “Hold tight to your anger, and don’t fall to your fears.”

In “Death of My Home Town,” he sings of the place where he grew up:

The Marauders raided in the dark

And brought death to my home town

They destroyed our families, factories

And they took our homes

They left our bodies in the plains

The vultures picked our bones.

Roots

Springsteen is firmly rooted in the tradition of America’s great popular singer-songwriters. He writes of love, death and loss, loneliness, growing up, and work, but also of resistance and rebellion, much of it couched in religious metaphor about the search for the promised land within the American Dream. Narrative songs such as ‘”Thunder Road” and “The River” stand comparison with the very best of popular songs but also cast a nod in the direction of Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, and John Steinbeck.

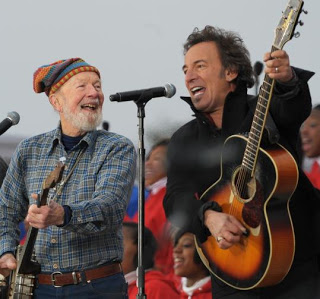

He has pursued this lineage as a conscious choice. He has read widely, sung with Pete Seeger, and recorded gospel music and labour and civil rights movement songs. The various themes are deliberately brought together in his latest album to “contextualise historically that this has happened before.”

This is most notable in “We Are Alive” with its implicit reference to “The Ballad of Joe Hill.” Here the spirits of the strikers killed in the 1877 transport strike in Maryland join with civil rights protesters killed in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963, and Mexican migrants currently dying in the southern desert:

We are alive

And though our bodies lie alone here in the dark

Our souls and spirits rise

To carry the fire and light the spark

To fight shoulder to shoulder and heart to heart

We are alive

Patriotism and class

Springsteen sings from the world of the U.S. manual working class. A world with union cards and union meeting halls; a world that has been taken apart over the past 30 years as industries have closed and many have been economic conscripts into imperial wars.

In giving voice to this, he calls upon elements of post-revolutionary, post-civil war America with a vision of a genuinely democratic working class republic — something that has been stolen by the marauders, the robber barons and bankers, but which is somehow still lived out in the resilience of its working people.

This patriotism is a central part of his being. He describes it as an “angry sort of patriotism,” something that he doesn’t want to cede to “the Right side of the street.” This has often led to misunderstanding, as was the case with “Born in the USA.” Deeply critical and acerbic about the America that came out of the Vietnam war, it was nevertheless — with its anthemic chorus — admired by Ronald Reagan.

Springsteen has become philosophical over such misinterpretations, recognizing that no artist has the “fascist power” to control the meaning of their words. It has led him to talk repeatedly of a dialogue with his audience. It is likely that a song on the current record, “We Take Care of Our Own,” will spark such a conversation. Again it is rhetorical, holding the American ideal up to the mirror and suggesting that “the road of good intentions has gone dry as a bone.”

In the U.S., where the flag is ever-present and the oath of allegiance spoken daily by children at school, it is easy to see why a fight over what it means to be “American” is a necessary plank of left politics. However, the tensions between the U.S. as revolutionary republic and imperial power are obvious.

If patriotism causes some problems, the class roots of his writings clearly provides him with a universal appeal. In 2010 at Hyde Park he opened with “London Calling,” a tribute to Joe Strummer and the Clash, and he has recalled the 1970s and his affinity with punk and how easy it is to “forget that class was only tangentially touched upon in popular music… at the time.”

It was noticeable that in the first European date of the tour in Seville, he spoke at length and in Spanish about how the workers were being made to pay for the crisis and saluting the indignados. The next day, the Andalucian UGT, the Spanish union federation, had a video of the speech on its website.

Defiance

Springsteen and the band have amassed a huge songbook, and while there is a range of musical styles and themes, the dark side of American life is never far from the surface. He celebrates the freedom of the streets (“We walk the way we want to walk/We talk the way we want to talk”), but the power of the police and the patrol car is never far away.

After New York City police shot dead an unarmed West African immigrant in 1999 he wrote the song “American Skin (41 Shots)” and in defiance of the NYPD played it at Madison Square Garden. In response they refused the normal courtesy escort for the band, called for a boycott of his shows and organized vociferous anti-Springsteen protests.

With the recession, and the death of his close friend Clarence Clemons, this darker side has taken the foreground. Enraged by the destruction of the material world of the working class, whereby “the banker man grows fatter, the working man grows thin,” he goads them to

Bring on your wrecking ball

C’mon and take your best shot

Let me see what you’ve got

Bring on your wrecking ballBecause we will survive, and like the “Jack of all Trades,”

You use what you’ve got

And you learn to make do

You take the old, you make it new

If I had me a gun I’d find the

bastards and shoot ’em on sight

Music and politics

The contradiction involved in Springsteen, now a multi-millionaire, singing with the voice of the poor and oppressed, is obvious. He is not alone here but his resolution of the problem has been unique. His solution was to tour, to play to large stadium audiences, tell the stories and keep the flame alive.

He talks about singing with the band as his “job of work,” and of the “hardcore work thing” shared by all the band members. On stage he will talk of the “foolishness of rock and roll.” In a master class with young musicians he stressed the need to understand their art as being both intrinsically trivial and “more important than death itself.”

While cynics would say that he does all this for the money, and he would agree that the money is important, there is more to it than that. This was made clear when Michael Sandel selected a Springsteen concert as one example of “What Money Can’t Buy” in his new book on the moral limits of markets.

Criticising economists in the U.S., who have argued that the band could net an additional £4 million for every concert with the “correct” pricing policy, Sandel points out that pricing out the people who understand and want to listen to and sing with the songs would change the nature of the concert, making it worthless.

Given his celebrity status, it is difficult to see how Springsteen can keep in touch with life on the streets and retain the voice to sing in the way he does. When asked, he talks of remaining “interested and awake.” He is wary of formal politics and though he had clear hopes for the Obama administration — he played at the inauguration (see below) — his disappointment is palpable. He has been energized by the Occupy Wall Street movement and has hopes that this can change the “national conversation,” focusing it on inequality for the first time for 30 years.

Wrecking Ball is his contribution to this conversation.

Playing for the president

Bruce Springsteen long avoided commenting on White House politics after Ronald Reagan famously misappropriated “Born in the USA” during his reelection campaign. The president ignored the song’s searing critique to claim it contained “a message of hope” that he would make reality if reelected. At the time Springsteen described it as a “manipulation.”

George W Bush and the Iraq War caused him to re-think. In 2004 he backed the Democratic candidate, John Kerry, playing 33 concerts as part of the “Vote for Change” tour. He wrote that “for the last 25 years I have always stayed one step away from partisan politics. This year, however, for many of us the stakes have risen too high to sit this election out.”

After Bush’s re-election Springsteen became an increasingly outspoken critic. In response to Hurricane Katrina he adapted Blind Alfred Reed’s protest song about the Great Depression, “How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live?,” transposing the original character of the song’s charlatan doctor onto Bush. He dedicated it to “President Bystander.”

Springsteen publicly backed Obama when the future president was still battling Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination. He enthused: “After the terrible damage done over the past eight years, a great American reclamation project needs to be undertaken. I believe that Senator Obama is the best candidate to lead that project.” Springsteen played at several election rallies — and the president’s inauguration concert.

To coincide with the inauguration he released the upbeat album Working on a Dream. The title track echoed that of Obama’s autobiography Dreams from My Father. But the album itself lacked direction. The new cheery Bruce had lost his distinctive voice.

Wrecking Ball has seen Springsteen reclaim old territory. As he acknowledged at a press conference in Paris, “You can never go wrong with pissed off and rock ’n’ roll,” and these songs are angrier than anything he’s penned before. Some of that anger is clearly directed at Obama.

Springsteen was only cautiously critical of the president in Paris: “He kept General Motors alive, he got through healthcare — though not the public system I would have wanted… But big business still has too much say in government and there have not been as many middle or working class voices in the administration as I expected. I thought Guantanamo would have been closed by now.” His music, however, offers a far more damning assessment. The single ‘We Take Care of Our Own’ tackles not only Obama’s America but also Springsteen’s involvement in party politics:

I been knocking on the door that holds the throne,

I been stumbling on good hearts turned to stone,

The road of good intentions has gone dry as a boneSpringsteen has said he’ll be staying on the sidelines during the 2012 election, commenting that ‘the artist is supposed to be the canary in the cage’. That hasn’t stopped the Obama campaign putting ‘We Take Care of Our Own’ on the official ‘campaign soundtrack’. It seems that Obama, like Reagan, recognises the power of Springsteen’s critical patriotism, even if he fails to recognise its critique.

— Emma Hughes / Red Pepper

[Huw Beynon, Steve Davies, and Emma Hughes write for Red Pepper, a bi-monthly magazine and website of left politics and culture based in London.]