Beats are back bigger than before:

A Rag Blog interview with

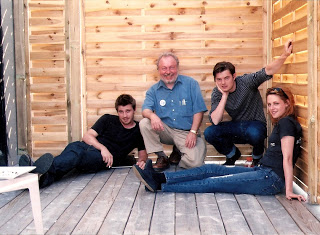

Kerouac scholar Gerald Nicosia

By Jonah Raskin | The Rag Blog | April 16, 2012

For decades, the Illinois-born writer, Gerald Nicosia, has made it his business to follow the fortunes and misfortunes of the spunky writers of the Beat Generation. This year with three new Beat movies — Kill Your Darlings, Big Sur, and On the Road — he’s as vigilant and as outspoken as ever.

He’s also waiting impatiently for the films to arrive at his neighborhood theater. Daniel Radcliffe of Harry Potter fame stars as Allen Ginsberg in Kill Your Darlings. Walter Salles, the director of The Motorcycle Diaries, directs the movie version of Kerouac’s novel, On the Road. An adviser on Salles’s film, Nicosia played a big behind-the-scenes role, and he’s betting that it will help spread the rebellious spirit of the Beats.

The author of a hefty biography of Jack Kerouac entitled Memory Babe, and a poet in his own right, Nicosia carries on the cultural and spiritual legacy of his literary heroes. For him, American literature is the literature of protest and rebellion that goes back to Henry David Thoreau and that includes Jack London, the socialist adventurer, and the tribe of Chicago writers such as Nelson Algren, author of A Walk on the Wild Side.

Though he lives in bucolic Marin County, California, he walks and talks with the gusto of Chicago and its rough-and-tumble novelists and poets. I’ve known Nicosia for 30 years; we first met after a poetry reading that Allen Ginsberg gave at College of Marin.

In 2005, we launched a 50th anniversary celebration for Howl at the San Francisco Public Library with crowds standing in the aisles and at the back of the theater. In 2007, we produced a 50th anniversary celebration for On the Road at the Jewish Community Center in San Francisco, with more than 600 people in the audience.

When I heard that three new movies about the Beats were on the way to movie screens around the world I thought it was time to talk to Nicosia again and find out what he was thinking about Kerouac, Ginsberg, Burroughs, and their friends and lovers.

Jonah Raskin: With new movies about the Beats coming to theaters, what would you hope Americans learn about Kerouac, Ginsberg, Cassady, and their wives and girlfriends?

Gerald Nicosia: That they were responding to an urgency in America, a wrong direction taken, a loss of community, a loss of brotherly love, a loss of a moral center.

You worked as an adviser to the film version of On the Road. What suggestions did you make to the actors and the director?

I told the actors not to worry about getting the exact details of the lives they were portraying. I told them that what was important was to give people a taste of what the love of these people was all about. With the director, Walter Salles, I got into things more deeply. He wanted to talk about the main characters’ search for identity and for the father.

I told him I thought the brother relationship between Neal Cassady and Jack Kerouac was at the heart of the novel — these two outcasts, misfits, learning to care about and take care of each other, breaking down the walls of isolation that were being so rapidly erected in postwar World War II America.

Why do you think there are three Beats movies coming out now? Is 2012 like the 1950s when their books were first published?

The cash-in on the Beats began several years ago. Now, you have three estates, those of Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs, discovering that there is unlimited money to be made in marketing these properties in electronic media and film.

Will any of the new movies do justice to the Beats?

I have the highest hopes for the movie of On The Road, because it was made outside the Hollywood system, financed by a small European company, MK2, and made by people who genuinely care about Jack’s message, beginning with the director Walter Salles. I don’t think he was put under the same pressure to make a “hit” that American moviemakers are under.

When and where and how did you first become interested in Kerouac?

I was at the University of Illinois in Chicago, getting my master’s. My officemate was a hip kid from Harvard who kept dropping Kerouac’s name because he knew I hadn’t read him. This was 1972 — three years after Jack died. The Dharma Bums and On The Road were the only two Kerouac books in print. I was blown away by Kerouac’s compassion for the down-and-out, the working class, those on the wrong side of American capitalism.

On what side of capitalism were you raised?

My family was working class — my dad a mailman, his father a construction worker and chimney sweep; my mom’s father a barrel maker, my mom’s mom ran a grocery store, my mom a secretary all her life.

How do you explain the Beats? Kerouac came from a Catholic working class family. Ginsberg was from a Jewish left-wing family and William Burroughs was white Anglo Saxon protestant. What did they have in common?

Amiri Baraka says they all came from minorities not yet fully assimilated into the American capitalist dream. I would say they were individuals who, by birth, temperament, political persuasion, and economic status, did not fit in with materialistic, chauvinistic, and belligerent American society. They were trying to find a way they felt had existed during the Great Depression of the 1930s.

You spent years doing research about Jack Kerouac. What would you say was the biggest surprise?

Kerouac’s books portray a hero and narrator free and easy, confident, sure of his rebellion against the American system. In reality, Jack was torn between Catholicism, Buddhism, and his own demon-driven pursuit of kicks, between spirit and flesh, between mom’s house and the Beat coffeehouse, patriotism and subversion, men and women, society and solitude, carousing and meditation, sacred and profane, secular and divine. It’s a miracle he survived as long as he did.

For years the Sampas family controlled the Kerouac estate? For those who don’t know, who are they and what damage did they do?

Sam Sampas was Jack’s first friend who gave him the courage to be a poet despite the jeers of his working class community. Late in life, when Jack’s mom had a stroke and refused to go into a nursing home he married Stella Sampas, Sam’s older sister, to take care of his mother. The marriage was a disaster, and Jack was about to divorce her when he died of liver disease from drinking at 47.

What happened with the will of Jack’s mother?

Stella forged Gabrielle Kerouac’s signature, thus stealing the estate from her grandchildren: Jack’s daughter, Jan Kerouac, and Jack’s nephew, Paul Blake, Jr. The damage they did was to sell Kerouac’s archive into private hands. Not one of the 9 or 10 manuscripts Jack wrote on long rolls of paper is now in a library where it can be studied.

I’ve heard it said that if it weren’t for Ginsberg and his savvy with promotion and public relations there would be no Beat Generation. How important was he in the marketing of his friends and their books?

He was very important — both in terms of things he wrote, and in schmoozing people in positions of power who could help the Beats get recognized. His thousands of readings carried the Beat message to millions of people.

Ginsberg, Kerouac, Burroughs, and Cassady knew one another from New York in the 1940s. How was that time and place significant for their development?

I think for all of them the key was to break out of the conformity, narrow-mindedness, and materialism that New York represented. Neal Cassady with his visions of Western individualism provided a way out for Ginsberg and Kerouac; for Burroughs the way out was through Tangier, Paris, and London, and finding more freedom in older cultures.

If they were alive today — the major figures of the Beat Generation — what do you think they would be doing now?

Kerouac would be writing. Cassady would be taking Viagra and chasing women. Ginsberg would be teaching. Burroughs would be taking his daily Methadone and plotting his next novel. They were driven people, on a mission, and only death could stop them.

We know now that there were women of the Beat Generation and that they wrote books. What do their books add to those written by their lovers, husbands, and boyfriends?

There was a heavy price to be paid for that male-led revolution. Somebody had to support it by hard work and carrying the daily load, the family load, that those male revolutionaries didn’t have time or inclination for.

In what ways do you think the Beats led to the rebellion and the protests of the 1960s?

They absolutely made the crack in Fifties consciousness, through which the counterculture of the Sixties poured. It couldn’t have entered without that wedge driven into the concrete wall of Eisenhower-McCarthy-Billy Graham America.

The Beats became a global phenomenon. What is it about them that appealed to citizens of the world?

They are citizens of the world; they speak as citizens of the world. It was a rare American ecumenical movement — even more so than the Transcendentalists, who were also reading Asian and Indian texts. The Beats actually went to those places, mingled with people, shared their writings, and learned from other cultures. I think people in other countries see this as a rare phenomenon among Americans.

The Beats didn’t do anything in moderation. If you knew them back in the day would you have cautioned them not to be as intense as they were?

No, you can’t slow down intense people. They have to burn at their own rate. People on a mission are unstoppable. God bless them for it. It would be a poorer, more miserable world without them.

For someone nineteenth or twenty years old now what Beat books would you recommend they read?

On the Road, The Dharma Bums, Desolation Angels by Kerouac. Howl, Kaddish, and The Fall of America by Ginsberg. Most of Burroughs is going to go over their heads, unless they’re lit majors. Gregory Corso’s poems, “Marriage” and “Bomb.” Diane Di Prima’s Revolutionary Letters, Ted Joans’s Teducation, Bob Kaufman’s Cranial Guitar, Jack Micheline’s River of Red Wine, and Ray Bremser’s Poems of Madness and Cherub.

[Jonah Raskin is the author of American Scream: Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” and the Making of the Beat Generation and a regular contributor to The Rag Blog. Read more articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog.]

The Rag Blog

Jack Kerouac became a stone reactionary late in his life. He disliked hippies intensely.

Not exactly. On the Buckley interview in 1968 (FIRING LINE) he said, “The hippies are better kids than the Beats.” He was troubled by things like burning or desecrating the American flag (since he had the French-Canadian immigrant’s love for America), and he didn’t like provocations to violence, like Jerry Rubin shouting, “Murder your parents,” whe he loved and lived with his mother. He wa also not pro Vietnam War, as he has been painted. He didn’t like the attacks on soldiers, and said he wanted to “put in a good word for the grunts slogging through the mud in Vietnam”–because most of those grunts were workingclass like himself. But he ridiculed the politicians who made the war, and claimed it was a conspiracy on both sides to sell and get American jeeps, which wasn’t so far from the truth.

Yet, Barry Gifford writes in Kerouac’s Town that when he visited Stella Sampas in 1973, Gabrielle Kerouac was still capable of both writing on the back of Allen Ginsberg’s letter to her, “Ginsbergh go to hell” as well as keeping up a steady stream of letters to her family.

Furthermore, stating that Stella Kerouac forged Gabrielle’s name is both arrogant and ignorant; Gerry wasn’t there nor did he have any evidence that she ever woudl or did.

It even makes less sense knowing that Stella, for the rest of her life, did practically nothing with her husband’s archive, even when she fell in such a state of such indigence that she resorted to wearing Jack’s old t-shirts for lack of new clothes.

A reckless and useless claim.

Raskin should have asked Nicosia why he was trying to trademark Kerouac’s name and why he sold him out to Levi-Straus.