|

| Nathan Schneider, June 17, 2012. Photo from Occupy. |

Interview with Occupy’s Nathan Schneider:

Anarchy, activism, and radical Catholicism

By Jonah Raskin | The Rag Blog | September 19, 2013

“It’s hard to pick a revolution about which one doesn’t have major misgivings. But they also have peak moments: the nuns kneeling before Marcos’ tanks in the Philippines; the queer crusaders emerging out of the Sixties; the cacophonous assemblies at the Paris Commune; the pockets of anarchist rule in Catalonia; the Christians and Muslims in Tahrir guarding one another’s prayers.” — Nathan Schneider

If Nathan Schneider had a middle name it might be “Contrary” or “Confrontational.” There isn’t a sentence that he writes or speaks that’s not provocative. In that sense, he’s a child of the Sixties, though he wasn’t born until the Reagan 1980s, and more precisely in 1984, the year that George Orwell warned us against.

“Half Jewish,” as he calls himself, he grew up in the free-floating spiritual environment that characterized the end of the twentieth century in America, which meant that he was touched by secular Judaism, secular Christianity, and “a strong dose of Eastern Spirituality” — through his mother. Not surprisingly, given his family and background and the force of his own quest for a spiritual matrix, he converted to Catholicism at the age of 18.

After he graduated from public schools in Virginia, he attended Brown and then the University of California at Santa Barbara, but gave up on academia to pursue his “education through journalism.” Schneider has been connected, as an observer and a participant, to the Occupy Movement for two years, beginning in 2011 and continuing until the present.

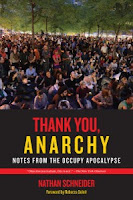

He tells the story of his conversion to Catholicism in God in Proof, and the story of his engagement with Occupy in Thank You, Anarchy which Rebecca Solnit calls, in her introduction, a “superb book.” It’s not the first book about Occupy but perhaps it’s the most comprehensive.

On the cusp of 30, Schneider has quickly become one of the “best and the brightest” — to borrow a phrase from the 1960s — in a generation of intellectuals and activists who are reinventing the American radical tradition. In the under-30 crowd, there’s probably no one with a deeper affinity for the Sixties than Schneider, and no one more eager to question the legacies of the Sixties than he — all of which makes his books and articles provocative and entertaining.

|

| Nathan Schneider, March 19, 2012. Photo from Occupy. |

Jonah Raskin: An Old Left friend of mine — Alexander Saxton — used to say that there was a gene for utopia. Do you think that there’s a gene for anarchy?

Nathan Schneider: Maybe it’s the same gene. Or maybe it’s a mood or a

moment. Many people who were talking the anarchist talk during Occupy

are now more or less back to doing the same-old-same-old. The Occupy

mood or moment was caused partly

by a failure — from the Democratic Party of Obama to radical left

organizations — to bring young folks into the fold. A few years after

Obama’s election – – with no limits on Wall Street or the security state

— there were no viable alternatives. So, there

was a craving to do away with everything, take over a square and start

from scratch.

My Catholic friends tell me that I’m a closet Catholic. I’m motivated by guilt and by the need to confess. There’s more to Catholicism than guilt and confession isn’t there?

Guilt motivates me, too, but I don’t attribute that to Catholicism. Despite evidence to the contrary, thanks to 2,000 years of baggage, the Catholic Church is supposed to be a durable institution that helps people live out the gospel of faith, hope, and love. I’ve found a great deal of inspiration and support in communities of radical Catholics such as the Catholic Worker. But my faith is enlivened just as much by acts of witness that aren’t done by Catholics — and Occupy was chock full of them.

Do you wish you had been alive in 1968? If so what might you have done?

I might have kept to the sidelines. My mother was in France that year and my father in Southern California, yet their proximity to rebellion didn’t seem to impact them appreciably. Occupy could just as well have passed me by if I hadn’t happened to be in on it from the beginning. I had time on my hands.

What if you were alive in Paris in, say, 1789?

I would have liked to be a pamphleteer.

Or in a Nazi concentration camp in 1944?

I probably would have died, as members of my family did.

I remember Tom Hayden popularizing the notion that repression leads to resistance. In Chile, for example, repression lead to the death of a movement that had culminated in the election of Salvador Allende. Is there a more nuanced view of repression and resistance in Hayden’s?

In Occupy, repression inspired wider resistance only for the first few weeks. Occupiers, especially in early 2012, got addicted to repression and couldn’t understand why their arrests stopped inspiring the public. Movements in far more repressive regimes tend to understand this dynamic instinctively. Activists need to be strategic about how much to invite the repression of the state and how much to circumvent it.

What you attribute to Hayden is related to the horrible notion that “things have to get worse before they get better.” No Thanks!

When you say in Thank You, Anarchy that the revolution isn’t far off, what are you actually saying? What do you mean by “far off” and what do you mean by “revolution”?

I was thinking of a conversation I had with an Egyptian activist. I asked whether, she expected that Mubarak would be out of power. She said, “Not in a million years.” Social transformation is hard; when it happens it can seem so easy and inevitable, until it gets really hard again. In the passage you’re quoting from, I’m trying to play with the dialectic. As for what we mean by revolution, take your pick. I’m trying to talk about the way in which revolution can’t be talked about.

You have published two books this year? What other books do you have in the works?

My goodness, two’s not enough? They’ve got me plenty busy. But I am also working on an essay about dispensationalism, a popular form of apocalyptic theology.

What political writers have taught you the most about writing about politics?

Jeff Sharlet — who also writes at the intersection of politics and religion — has long been a mentor, though I can’t come close to imitating him. He introduced me to JoAnn Wypijewski who guided me at a formative time. As the initial occupation approached, I was reading Norman Mailer’s Armies of the Night — about the 1967 anti-war march on Washington — which I loved and hated, because all that seems to matter to Mailer is what he’s thinking. At times his thoughts are brilliant. Lastly, I’ve learned a lot from Joan Didion, especially how her thinking is less important than what she reveals.

How white was Occupy Wall Street?

|

| Schneider on Occupy. |

It started out pretty white, and then became less white and then white again. We saw some of the wrinkles in our supposedly post-racial society when it turned out that people didn’t know how to relate to each other across racial lines.

The other day, I saw a young black man in my neighborhood wearing one of Jay Z’s “Occupy All Streets” T-shirts. The movement forced Jay Z to discontinue those shirts. In Occupy Atlanta, John Lewis, a civil rights hero, was denied a chance to speak. A lot of the beauty in us and in our society that’s normally hidden under a bushel was allowed to shine in Occupy. So was a lot of ugliness.

Can you say more about Jay Z and the T-shirts?

People were very sensitive to rip-offs and co-optation. It was a tough decision because if the shirts had been around they might have led to more connections to communities of color.

Is there a revolution from the past that inspires you more than any other?

It’s hard to pick a revolution about which one doesn’t have major misgivings. Every revolution betrays. But they also have their peak moments: the nuns kneeling before Marcos’ tanks in the Philippines; the queer crusaders emerging out of the Sixties; the cacophonous assemblies at the Paris Commune; the pockets of anarchist rule in Catalonia; the Christians and Muslims in Tahrir guarding one another’s prayers. Still, it’s hard to pick one that I’d be willing to wish on anyone.

The Left used to have a monopoly on the word “contradictions.” Now it’s everywhere. What would you say were the main contradictions, in the Marxist/Maoist sense, of Occupy?

So many: autonomy and accountability, sanity and madness, order and mischief, creativity and frustration, occupation and colonization, relief and recovery, grievance and self-sufficiency, ecstasy and failure. The moment these contradictions resolved themselves, and one element in them came to dominate over the other, the dynamism went away.

Why do you think it is that every generation in America over the past 60 years or so has wanted to define itself in opposition to an earlier and an older generation? Why not emphasize continuities between generations?

Occupy had the potential to be powerfully cross-generational. From the outset, young folks were driving it, but they were very eager to hear from elders. They wanted advice, support and help. Many leading organizers had grown up in political families, and, while they viewed their parents as more moderate than themselves, they credited their upbringing for their politics.

Sounds like you have a theory on this.

I think that the Sixties generation of radicals had to rebel so hard against their parents that, when they became the new establishment in left wing groups, they had an Oedipal fear that later generations would do the same to them. So they didn’t make a priority of raising young leaders.

If you look around at the established radical organizations, especially in New York City, you’ll be hard-pressed to find more than a tiny minority of young people involved. But as those who turned out for Occupy showed, it’s not for lack of young activists. Before and after Occupy, young folks eager to get involved in radical politics had to hustle to find mentors and material support. Friends of mine affiliated with the political right don’t seem to have this problem.

Are you calling for defiance against older generations?

I’m trying to bridge the gaps between generations. I tend to get along with older people.

My favorite political quotation is from Gramsci about the pessimism of the intellect and the optimism of the will. What’s yours?

Mine is the entirety of the commencement speech that the poet-priest (and friend) Daniel Berrigan once gave at a Catholic prep school in Manhattan: “Know where you stand and stand there.” Not that I follow it, really — I just like it.

What’s your connection to Berrigan?

We met about five years ago. I started going to his monthly community suppers. We talked and saw that we had common interests. I see him regularly now, but his health is deteriorating rapidly. I don’t know how much longer he’ll be around.

In a nutshell what does anarchy mean to you?

A society in which some people don’t wield unnecessary power over others, and one in which the needs of all are put before the privileges of a few. “Anarchy” has so many connotations, and in the book I like to play off of several of them at once. It’s a very ambidextrous word: chaos, freedom, organization, and structurelessness. I want them all.

[Jonah Raskin, a regular contributor to The Rag Blog, is a professor emeritus at Sonoma State University and the author of For the Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman and American Scream: Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” and the Making of the Beat Generation. Read more articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog.]