|

| Margaret Randall, Berkeley, California, March 23, 2011. Photo © Scott Braley. |

Interview with Margaret Randall:

Feminist, poet, and oral historian of Che,

Fidel, and the Cuban revolution

“Che, even on his early motorcycle adventure through Latin America, was deeply affected by human misery and beginning to figure out what he felt could be done to alleviate it.”

By Jonah Raskin | The Rag Blog | October 3, 2013

Margaret Randall, 77, lives today in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where her roots run as deep as they do in Mexico, Cuba, and Nicaragua where she has also lived for extended periods of time.

In the 1980s she was a woman without a country — or at least a woman without a legal passport. Born in New York in 1936, she dropped out of college, moved to Spain and then to Mexico where she married the poet, Sergio Mondragon, with whom she founded and edited the literary magazine, El Corno Emplumado (The Plumed Horn).

In 1968, after a year of involvement with the Mexican student movement, she went underground and escaped to Cuba where she lived until 1980, interviewing Cuban women and serving as a judge for the Casas de las Americas poetry contest and raising a family. Then, after four years in Sandanista Nicaragua, she returned to the U.S. where she was greeted by family members and friends — and declared persona non grata by the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

In 1969, when she had acquired Mexican citizenship she also simultaneously lost her American citizenship. Immigration officials stated that, in her writings, she had expressed views “against the good order and happiness of the United States.” After a five-year legal battle, the Center for Constitutional Rights won Randall’s case and succeeded in having her U.S. citizenship reinstated.

The author of more than 120 books, she lives with painter and teacher Barbara Byers. In 1990, Randall was awarded the Lillian Hellman and Dashiell Hammett grant for writers persecuted by political repression. In 2004, she was the first recipient of PEN New Mexico’s Dorothy Doyle Lifetime Achievement Award for Writing and Human Rights Activism.

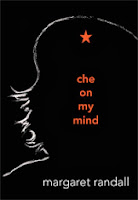

She has four children and10 grandchildren. Duke University Press has just published Che On My Mind, which Noam Chomsky calls “a compelling personal meditation.”

|

| Randall with her husband, the Mexican poet Sergio Mondragon. |

Jonah Raskin: We’re close to the anniversary of Che’s death. He was murdered 46 years ago, on October 8, 1967. In some ways he might not recognize the world of 2013.

Margaret Randall: Would Che recognize the world of 2013? I’m inclined to think he would. One of the fascinating things about him is that he had a far-ranging analytical mind. He was curious about everything and knew a lot of political theory, revolutionary practice, medicine, anthropology, art, language, and more.

So, extrapolating from this I believe our world would not have surprised him. It would be more interesting to know how he might gotten from “there” to “here.” We’ll never know. With his murder those who feared him put an end to his astonishing capacity to see history and to process it. What we’re left with is a story made static by its unnatural end.

Your own life was intense in this period. Can you say something about it?

I was part of the Mexican student movement of 1968 that was brutally repressed; hundreds were shot and killed by the army. A year later, in 1969, we were preparing to honor those who had died. Two paramilitary guys forced there way into my house at gunpoint and stole my passport. I reported it stolen but the Mexican government refused to give me another. That’s when I went underground. I acquired fake papers, traveled to the U.S., then to Toronto and to Prague and from there then to Havana. My kids had gone on ahead of me and met me at the airport.

Was there an epiphany during the writing of the book?

The whole book was a kind of epiphany. Che had long fascinated me. I knew one of his sisters and a brother, too. I felt close to the family. I kept reading and rereading and than one day I just found myself writing. At first I thought it was going to be a short essay, then it turned into a book.

In Che On My Mind, you’re both critical of Che and at the same time empathetic. Did it take time for you to reach that vantage point where you saw his strengths and his flaws?

I’ve been ruminating on the man and his era — which was also mine — for almost half a century.

I imagine that if you had written a book about Che in, say, 1968, or even in 1975, it would have been a very different book. This book reflects who you are now in 2013 doesn’t it?

Absolutely. It’s a culmination of years of my own experience, losses, thinking and rethinking — observing how Che’s persona has been reflected in and used by generations for whom he’s been a model in one way or another.

The photos of Che that you include say a lot about him and his personality. The photo with his mother seems to reveal their deep connection, while the photo of him from 1963 in Havana smoking a big cigar suggests a kind of arrogance — at least to me. Do you have one favorite image of Che?

My favorite photograph of Che, or the image that haunts me most insistently, is the one taken on October 9, 1967, by Bolivian press photographer, Freddy Alborta, of the man lying dead in a schoolhouse in Bolivia. I reproduce it twice in my book, one full frame and again as a close-up of Che’s face. Although “lifeless” his features retain a mysterious quality — something between terrible foreboding and infinite calm. The CIA and Bolivian Army staged this photo shoot in order to prove that the guerrilla leader was dead. This image proved just the opposite.

Your book reflects your own personal journey from North America to Latin America — Mexico and Cuba and Nicaragua — and back to North America. At one time you might have said that living here was living “in the Belly of the Beast.” Is there an image or a metaphor you would use today to describe the USA?

Living in the U.S. today is like living on the far side of Alice’s Looking Glass or, as Eduardo Galeano has said, in a world that is upside down. Official wisdom is really smug deception. Criminality passes itself off as benevolence, and the 1% continues to ignore all the warming signs in a world it’s destroying.

It’s definitely difficult for guerrillas from the mountains to morph into government officials in the capital. Che did that for a while when he was president of the Bank of Cuba. Che as banker doesn’t fit the popular mythology does it, but its part of the picture.

Che was one among many who pointed out that winning a military campaign and restructuring society are very different endeavors, and that the latter is far more complex and difficult than the former. I believe that Che had immense courage, some valuable ideas, and also made some painful mistakes in both contexts. There is no doubt in my mind, though, that had his ideas about a new society continued to be implemented after he left Cuba, more of the revolution would exist in that country today.

I like the selections from Che’s letters that you have included. In several of them he seems to romanticize violence as when he writes about “the staccato singing of the machine guns.” Machine guns probably don’t really sing do they?

No, they don’t sing; they kill.

Why did you return to the United States after years of living in what might be called “exile”? Did you feel that you took that part of your journey as far as you could take it?

I missed my language, my culture, the space and colors of my New Mexico desert, my aging parents: all the components that together define home. And I was tired after so many years away, often on the front lines of battles that were and were not my own. I was close to 50. It was time to come home.

What do you miss most about the Latin American world that you knew?

I miss its rich cultures, extraordinary creativity, and unfailing hope in the face of forces that continue to exploit and usurp. I miss good Mexican mole, Cuban yuca al mojo de ajo, Nicaraguan tamales. I miss César Vallejo’s voice and all the voices of young poets who exist because he did. I miss my children, three of whom opted to remain in Latin America; and of course I miss my grandchildren whose lives are unfolding in Mexico and Uruguay.

You’re also critical of Fidel and Cuba in your book — including what you call “the stagnation.” Given the blockade and U.S. foreign policy on the one hand and the reliance on the Soviet Union for so long on the other hand, what choices did the Cubans really have?

I am critical of decisions I feel were paternalistic, didn’t display enough faith in the Cuban people themselves, discouraged healthy criticism, and further isolated a nation that is, after all, an island. Given the balance of power during the Cold War years, Cuba may not have had more viable options. Hindsight is always 20/20, as they say. When the Cuban revolution has been most open and embracing I believe it has achieved its greatest successes. This said, every time I revisit the country I come away with a palpable sense of justice and possibility I don’t experience anywhere else.

Edward Boorstein, the American economist who wrote about Cuba, told me a story about how Che became head of the national bank. In his version, it was Fidel who asked if there was anyone in a room of guerrillas who was an economist. Che raised his hand. Later, when he wasn’t very effective at the bank, Fidel went to him and said, “I thought you told me you knew economics.” Che replied, “I thought you asked if anyone was a communist.” You point out that the story may be apocryphal. What does the story say to you? How do you interpret it?

Popular culture tends to pick up and focus in on moments that illustrate deep truths, and then incorporate them into legend. I’m sure there is at least a kernel of truth in this story. The Cubans have a marvelous capacity to laugh at their own idiosyncrasies. If this story didn’t happen exactly as it is told, what remains significant is that changing society requires superhuman effort, often by people who have no particular training for the job and must invent as they go along. Making the effort is always better than saying, “We can’t do this because we don’t know how.”

For me the most sobering moment in your book isn’t the death of Che in Bolivia but the suicide of Haydee Santamaria, perhaps the most prominent of the revolutionary leaders, in 1980 in Cuba. What can you tell us about her suicide? How did she take her life? Did she leave a suicide note? Was her death covered up?

Her death wasn’t covered up. But, as with many such major events, in Cuba and elsewhere, we know what those who control the information want us to know. As far as I’m aware, she didn’t leave a note. But she left a life. Like Che, Haydée Santamaría was an exceptional human being. To me, she represented the very best humanity has to offer. She definitely envisioned and worked to create a better world. It must have been unbearably painful for her to have to live in the one that exists.

The chapter about Che and Haydée is the one in my book that means the most to me, the one on which I worked the hardest, and the one I believe embodies most completely what I want to say about the Cuban revolution, its central figures, that whole extraordinary swatch of history.

|

| Che in 1963 in his office in the Hotel Rivera in Havana. Photo by the French photographer Rene Burri, on assignment for Look magazine. |

You seem to be positive about the Weather Underground. You say that the organization remained “the voice of a certain radical faction” when the New Left declined. Do you admire the organization more than any other in the USA from that time?

I admired it at the time. I admired all those who dared speak out, rise up, and fight the power of U.S. hegemony and imperialist abuse of other nations and our own. And I continue to feel that admiration. I was also living somewhere else, though, and therefore in no position to observe or judge the excesses, the lack of connection many radical groups had with the lives of ordinary working people, certain sectarian or authoritarian ideas that created dangerous divisions and doomed brilliantly creative projects.

The young Che Guevara seems like a young Jack Kerouac in some ways; he was in search of “adventures” and “fun” to use his own words. Che went on his motorcycle journey about the same time that Kerouac was traveling across the U.S.A. And he was extraordinarily poetic, too, as when he wrote that, “words turn to prisons inhibiting my feelings.” Do you think he and the Beats would have been comrades on the road if they had met in say, 1955?

I can see them as comrades on the road if they had met in 1955, though probably not in 1965. The Beats were motivated by a rejection of the social hypocrisy pervasive in the U.S. throughout the 1950s. But their solutions involved lighting up and dropping out. Che, even on his early motorcycle adventure through Latin America, was deeply affected by human misery and beginning to figure out what he felt could be done to alleviate it. Kerouac’s and Che’s roads diverged. But I definitely sense an underlying “brotherhood.”

Che was in New York in 1964 and 1965. He talked about sleeping in a hammock in Central Park — the closest he could get to a jungle. What thoughts do you have about him in New York?

I wasn’t there. But I imagine he was lonely, enraged much of the time, deeply curious as he always was about places with which he was unfamiliar, perceptive, and perhaps a little bit in love.

If you had met him what might you have wanted to ask him?

At this point in my life all I can be sure of is that I would not, back then, have been able to ask the right questions — of him or anyone else. It’s taken me a while to be able to formulate the questions I do ask in my book.

Though he used the Spanish word for “faggot” to describe homosexuals you don’t think he was homophobic?

I struggled with this in my book, and I am honest about the process of that struggle. Of course, there was a great deal of the macho in Guevara, and his use of the word “faggot” was disgusting, unforgivable. It was also an almost unthinking part of the popular culture at the time. I came to the conclusion, after looking closely at the role he played or did not play in the actual repression of homosexuals in Cuba, that he was not one of those for whom that egregious repression was personally important.

And looking at other ways in which he departed from the norm, I came to feel that — like Fidel — had he lived long enough to experience the call for gay rights, he would have endorsed them. Che was a man of his time, but deeply principled.

Your book might be described as a feminist reading of Che’s life and work. Do you see it that way?

Absolutely. Insofar as feminism is a framework for looking at power relations, I read everything from a feminist point of view. I also see this as a poet’s book, a poetic reading of a life.

[Jonah Raskin, a professor emeritus at Sonoma State University and a regular contributor to The Rag Blog, is the author of American Scream: Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” and the Making of the Beat Generation, and the editor of The Radical Jack London: Writings on War and Revolution. Read more articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog.]