An interview with Tom Hurwitz:

Superstar of contemporary

American cinematography

By Jonah Raskin | The Rag Blog | January 23, 2013

“I love going to the movies. Movies are one of the great anachronisms, where collective craft, design, and technology merge with individual talent, as in the building of a medieval cathedral.” — Tom Hurwitz

I love talking shop, especially with those who work in shops, whether they’re real old-fashioned and gritty or the most up-to-date and sophisticated. Tom Hurwitz, whom I first met in 1968 on the rough-and-tumble campus of Columbia University, is my idea of the ideal filmmaker to talk with about the big glittering shop that makes images and that we all call Hollywood.

Hurwitz is a straight shooter in more ways than one, and a real craftsman — a versatile cinematographer — who knows the film industry from the inside out. What other living moviemaker can you name who talks about capitalism and about art in the same breath and who can practically recite all the scenes in Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane?

Hell, he’s also the son of the legendary documentary filmmaker, Leo Hurwitz (1909-1991), who was, for a time, blacklisted, and who continued to make films, despite it. His stepmother, Peggy Lawson, was a filmmaker and film editor and stars in Dialogue with a Woman Departed (1981) that Leo Hurwitz wrote and directed and that’s a tribute to her and her work.

Tom Hurwitz made his first picture — Last Summer Won’t Happen (1968) — with Peter Gessner when he was 20, and, while he’s taken a few detours in life, he’s followed the script that seems to have been written for him by the gods of cinema. He’s worked on — to name just a few pictures – Creep Show 2 (1987), Wild Man Blues (1997), Ghosts of Abu Ghraib (2007), and Queen of Versailles (2012) that wasn’t nominated for an Oscar — damn it! — but that did win awards at Sundance and from the Directors Guild of America.

Born in 1947 and reared in New York, he’s filmed TV programs such as Down and Out in America (1986), and Faith and Doubt at Ground Zero (2002) both for PBS, as well as movies for the big screen, and has won dozens of awards including two Emmys, along with Sundance and Jerusalem Film Festival awards for best cinematography. Then, too, he’s on the faculty of New York’s School of Visual Arts and a founding member of its MFA program in the social documentary.

For years, I had close friends in Hollywood: Mark Rosenberg at Warner Brothers who produced, with his wife Paul Weinstein, The Fabulous Baker Boys (1989) and Flesh and Bone (1993); and Bert Schneider who produced Easy Rider (1969) and Five Easy Pieces (1970), as well as the award-winning documentary about Vietnam, Winning Hearts and Minds (1974). Rosenberg died in 1992 at the age of 44; Schneider died in 2012 at the age of 78.

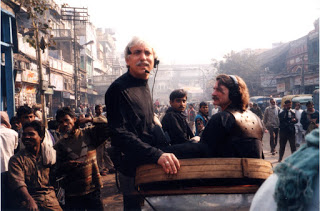

Tom Hurwitz is one of the few individuals I know who’s still working in film, still very much alive, and still kicking up a storm of ideas and images for the screen. With the 2012 Academy Awards on the horizon, I fired off a round of questions about movies and moviemakers. Hurwitz was about to leave for India to make yet another movies, but he fired back his answers.

Jonah Raskin: Too bad your film Queen of Versailles wasn’t nominated for an Oscar.

Tom Hurwitz: I shot the film and I’m very proud to have been part of it. As I see it, Queen tells a Shakespearian story about the decline of values, the dispersion of families, and the bursting of bubbles in this wretched stage of capitalism we inhabit. It tells the story by following the lives of a household that begins in unimaginable wealth.

Was it a fairly straightforward picture to make?

Making it was difficult. You wouldn’t think that filming the family of a failing billionaire would be taxing. But when you see the movie, you can appreciate that maintaining the proper documentary relationship over a long time was hard. What was wonderful about shooting Queen was working with the director, Lauren Greenfield. She’s a great still photographer who also has a great sense of story. We speak the same language, and I loved the challenge of working up to her standards, making my motion pictures work with the style of her stills.

What are, from your perspective, the best five feature films of 2012?

Anna Karenina uses the device of the theatrical stage to turn a book into a movie — always a challenge — and to surmount the limitations of budget. It takes on a dream-like character with a miraculous effect.

Then there’s Zero Dark Thirty, a film that asks big questions. It felt more real and immediate than any other film this year, with acting, design, direction, photography, and sound all serving a unified end. When the first explosion happened in the film, I was on the floor before I knew it — and I was in Afghanistan. It says something that the filmmaker, Kathryn Bigelow, cares enough about reality to make the explosions sound more real than in any other film that I’ve seen.

Moonrise Kingdom is an almost perfect product of Wes Anderson’s imagination. It’s a fantasy that resides in the twilight land of childhood, in the lives of its marvelously understated characters, in their island world, and in the brilliant design and execution of the film. I kept thinking about it, savoring it like a wonderful meal, or perhaps like a dream.

What about documentaries?

Five Broken Cameras, made by a Palestinian Arab and an Israeli Jew, is seen through the eyes of a villager inside the occupied territories of the West Bank. The film is shot with camera after camera over a 10-year period beginning with the birth of a boy, and as the State of Israel tries to cut off the village off from its fields, and as settlers try to take the land itself.

The residents fight back nonviolently. The toll of the occupation on the lives of the Arabs and on the souls of the Israelis is made painfully clear. The film is told like an historical novel with character development, revelation, and tragedy. It’s the best combination of micro and macro documentary that I’ve ever seen.

Do you watch the Academy Awards?

I only watch them all the way through when a film I’ve photographed is up for an award. I went a couple of times and then I had to sit through them. I usually watch the beginning, get bored, and check the results in the paper or on line.

Are the Oscars mostly a publicity event for the movie industry?

I don’t take the awards themselves lightly. For members of the Academy, November and December are crazy because we try to watch all the films in contention, nominate, and vote. I don’t agree with many of the choices, but I care that the industry goes through the ritual of holding up its best, as cheesy as the event often is.

The chance to walk down the red carpet — even though folks like me are shunted down the non-celebrity lane — is worth the ticket, the limo, and the suit. For five minutes, you walk slowly through a world where shadows are banished, wrinkles and imperfections don’t show, and every watching face holds a camera.

Do you actually go to a movie theater and watch a new film?

I love going to the movies. Movies are one of the great anachronisms, where collective craft, design, and technology merge with individual talent, as in the building of a medieval cathedral. Films ought to be appreciated in a social context. Watching a film alone on the screen in my living room, as I often do, isn’t the same thing.

You were part of the anti-war movement and a protester at Columbia in the 1960’s. Are there others with similar political backgrounds in the movie industry today?

I think any sensible person in the industry who is old enough to have been in the 1960’s political movements is retired. I usually work with people from 10 years younger to less than half my age. Haskell Wexler, a mentor, was an activist in the 1960’s. He’s more of a die-hard than I am and 20 years older. In my age group — Connie Field, Barbara Kopple, Deborah Schaeffer, Mark Weiss, and Deborah Dickson — all spent time in the movement.

Does anyone in Hollywood make what might be called a “radical movie,” and if so how does that happen?

Most of what’s produced in Hollywood now is television. The movie industry, even though some great films were produced this year, is in a huge fog about where it’s going. I don’t think narrative film knows how to be radical. It’s not alone. Neither does television — as good as some of it may be, or the theater.

It’s not only that radical art doesn’t get distributed, it’s that the radical voice is often confused and muted. That may be one of the reasons for the present flowering of documentary films. We may be in a time where reality speaks clearest of all.

What impact does Sundance have on moviemaking today?

Sundance Festival is a great place to see people I know who I would never otherwise get to spend time with. Also, I get to view tons of good, near-good, and occasional great films– so many that my brain becomes mush. Filmmakers who go there leave inspired by the attention, companionship, and good work. Producers sell their films to distributors there, though I’d hate to have to be part of that sales race.

I have friends who say the last really good Hollywood movies were made in the 1930s. Is that perversity or blindness?

There were great films made in Hollywood in the 1930’s, but to say that they were the last great films is obtuse. Thirties films are mannered, even the best of them, with a set of conventions: visual, directorial, and acting. That the best of them succeed in spite of their rarefied air is a particular kind of grandeur. One might note that the social documentary film was invented in the 1930’s in New York, as a way to blow open the closed world of 1930’s Hollywood.

What films do you turn to again and again?

I watch a lot of films over and over because I teach graduate students every year and analyze the images. It’s another way of appreciating films other than just being inspired by them. I have a list of what I consider perfectly photographed films.

If a director and I haven’t already worked together I always try to screen The Conformist (1970), which Vittorio Storaro shot for Bernardo Bertolucci. I talk about the way the image is at once hugely expressive, yet always works at the service of the story and never just calls attention to itself arbitrarily. That is the highest calling of cinematography in narrative and in documentary. I call it the articulate image. Even if we don’t want the film to look anything like The Conformist, watching it together starts the best of conversations. Sometimes I see it to make myself feel good about the possibilities of the image.

What movie made in the last, say, 10 years would you like to be able to say, “That’s my movie.”

I’d pick a documentary called War/Dance (2007) made by Sean and Andrea Fine. It’s about children in a refugee camp in Uganda and their struggle to mount a successful team for a national dance competition. The children become characters in their own amazing drama. The cinematography lifts the heart with its beauty and perfectly compliments the story and the subject.

What filmmakers have you learned from?

First and most important my father, Leo Hurwitz, who directed some of the first American political documentaries in the 1930’s and one of the greatest ever made, Native Land. It was photographed by Paul Strand, the great American photographer, and narrated by Paul Robeson. I love Native Land because it’s brilliantly shot and structured. It influenced me, of course, and a generation of American documentarians here in New York who moved into television in the 1950’s.

Next, there are a group of influential filmmakers who I call my “aunts and uncles”: Sydney Meyers, Manny Kirchheimer, Peggy Lawson, Bill Jersey, Al and David Maysles, Ricky Leacock, Haskell Wexler, Owen Roisman, Charlotte Zwerin, Dede Allen, and Bob Young.

And then, more at a distance: Orson Welles, Nicholas Roeg, James Wong Howe, Gordy Willis, Phillip Roussalot, Peter Suschitzky, Peter Biziou, Nestor Almendros, Sven Nyquist, Terrence Malik, Bernardo Bertolucci, Chris Marker, Jean Rouche, Alain Resnais, Wong Kar Wai, Akiro Kurasawa, and I’m leaving out dozens.

You made movies as a 20-year-old. At 20 and 21 did you look into the future and see a career in the movies?

In 1968, when I looked into the future, I was scared shitless, though I had a film, Last Summer Won’t Happen, in the New York Film Festival. I had no more idea of how to make the next film than I did how to write a novel. I hadn’t lived, let alone learned my craft.

I went off and organized marines, and then a union local, and then took part in the successful defense of a political prisoner for five years. I took stills, sold some, and began to feel like I could go back and begin a career, which I did at 26, with a full apprenticeship behind me. I moved on from there to become a journeyman.

If you had unlimited funds is there a movie you’d love to make now?

I’d love to make a film about the last free tigers on earth that live in a giant mangrove swamp in South Asia that’s the size of Rhode Island. I want to make it through the eyes of Alan Rabinowitz, a Jewish kid from Brooklyn, who grew up to be one of the great protectors of wildlife in the world, and a master of the martial arts. The film about the tigers needs another million dollars in addition to what the producers have already raised, but shooting starts soon in India and Bangladesh.

When someone hands you a script and wants you to read it, what do you look for?

For 15 years I received dozens of scripts to read. They would be disappointing nine-tenths of the time. Sometimes I would have to take one because I really needed the work, and so Creep Show 2 was born. Now, luckily, directors call or email and ask, “Do you want to shoot a documentary about a company of reservists who fly helicopters and are deployed to Afghanistan for a year?” That became Kansas to Kandahar (2006). Or “What about filming a crazy, fascinating, rich family in Orlando, Florida?” That turned into Queen of Versailles. Or, “Would you consider work on the first avowedly gay bishop in Christendom?” That evolved into Love Free or Die (2012). Now, I get to say, which I didn’t at the beginning, “When do we start?”

[Jonah Raskin, a frequent contributor to The Rag Blog, is the author of Field Days: A Year of Farming, Eating, and Drinking Wine in California, and Marijuanaland: Dispatches from an American War. He is a professor emeritus at Sonoma State University. Read more articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog.]

I enjoyed this article, remember Tom from Columbia, 1968, love the writer Jonah Raskin, and will look for some of the films mentioned in Netflix.