|

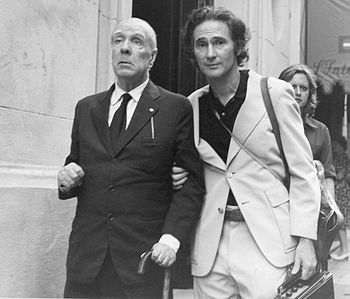

| Willis Barnstone, right, with Jorge Luis Borges, Buenos Aires, 1975. |

Interview with Willis Barnstone:

Hermit, translator, ardent baseball fan

“People called Babe Ruth a womanizer and a drunk. Southerners suspected that he was part black. Protestants denounced him because he was Catholic. He never forgot that he was an orphan. Unlike other baseball greats, he was the opposite of a racist and a man with a desperate love for living.” — Willis Barnstone

By Jonah Raskin | The Rag Blog | March 28, 2013

Willis Barnstone has lived most of his life in big cities around the world — New York, Athens, Paris, Mexico City, and Buenos Aires — but he was born in Lewiston, Maine, in 1926. During the Chinese Cultural Revolution, Zhou Enlai invited him to Beijing. Decades earlier — in the late 1940s and early 1950s — he taught in Greece; in many ways he’s been more at home in the world of the ancient Greeks than he has been in the modern world.

Barnstone helped to bring the work of the Argentinian author, Jorge Luis Borges, to the attention of the English-speaking world. He translated the poetry of Mao Zedong.

A poet and memoirist himself, he reads his own work aloud with his daughter, Aliki Barnstone, and his son Tony. At 85, he’s still vigorous, still translating, and still traveling widely.

|

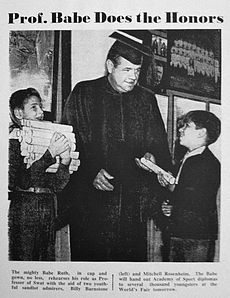

| Willis Barnstone, on left, with Babe Ruth, New York, 1939. |

Jonah Raskin: Since baseball is back for yet another season could we start with your own memories of Babe Ruth?

Willis Barnstone: I met the Babe when I was 11 and he was 44. We lived in the same building on Riverside Drive in New York. I lived on the second floor. Ruth was on the 18th. It was April 30, 1939.

What was the occasion?

He was going to give out a few thousand diplomas from the fictitious Academy of Sports at the New York World’s Fair. A photographer from the Daily News took a photo of me and the Babe and another kid my age. We were on the front page of the newspaper on May 1, 1939. I was in my boy scout uninform. Ruth didn’t wear his Yankee uniform, but a black cap and gown.

When you look back at Babe Ruth how do you remember him?

People called him a womanizer and a drunk. Southerners suspected that he was part black. Protestants denounced him because he was Catholic. I thought of him as the immortal Babe. He never forgot that he was an orphan. Unlike other baseball greats, such as Ty Cobb, he was the opposite of a racist and a man with a desperate love for living.

You received one of Ruth’s diplomas from the Academy of Sport and yet you never went into the world of sports, but rather into the academic world.

I did play stickball as a kid on 89th street in Manhattan. As an undergraduate, I went to Bowdoin College in Maine and then to Columbia and to Yale, where I received my Ph.D.

And you taught at colleges and universities in the United States and around the world.

I was at Wesleyan and then at the University of Indiana where I was a professor of comparative literature and Spanish. I taught Greek at Colgate and I was a visiting Fulbright professor in Beijing.

You’ve been a translator for most of your life. Through your translations you’ve created a whole series of bridges between cultures and societies. And you’ve lived in many different parts of the world — Greece, China, France, and Argentina.

When I travel I seldom feel like a foreigner. In Greece during their civil war and in Buenos Aires during their “dirty war,” I made deep connections with Greeks and Argentinians. If you’re a sympathetic outsider you get inside a country.

For my generation 1968 was a real watershed. What year is pivotal for you and your generation?

Personally, it was 1948, the year I went to Paris, began graduate school at the Sorbonne, and compiled my first book of poems that was published in 1949. The Spanish Civil War, from 1936-1939, was my first international political cause. As for my generation, the pivotal time was World War II and then the Korean War when I was drafted.

How did you experience the Sixties?

I remember going to Auschwitz in Poland, the grimmest, most sordid place in the world. I went on to Lapland, roamed through Brazil and spent time with the Beats. My friendships with Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso, and Allen Ginsberg go back to the 1950s, not the 1960s. For me, the 1950s were a more vibrant time of change and revolution than the fabled 1960s.

Is seems to me that you have no fixed identity.

|

| Barnstone in China, 2006. |

My central identity is as a poet, with a drift toward secular mysticism. I suppose I’m also a kind of tramp. The characters in literature with whom I identify the most are all on journeys, whether they’re Ulysses or Don Quixote. My heroes are picaros.

Is there a similarity between poetry and sports?

Poetry is a game, a way of creating the fantastic out of the ordinary, and baseball is also a game — mostly nonviolent — in which you try to hit the ball into the stars.

How did you feel during the witch-hunts and the Red Scare of the 1950s?

Like shit. But the 1980s, with Reagan, was worse. He was the incarnation of illiteracy and the assault on thought itself. Reagan killed you with a smile.

You live in Oakland, California now. What’s that like?

Oakland is a sad, troubled city. I’m an outsider and live like a hermit which is good for the pen. Since settling here 20 years ago, I have published more than a dozen books including translations of Sappho, the Bible, and the twentieth-century Spanish poet, Antonio Machado.

What, if any, are the cultural advantageous for a writer who lives in the “literary capitals” of the world?

I regret I’m not in a literary capital right now. When I go back to New York and Boston I breathe different. The advantage of living in a great city is that you long to get out of the city.

How is the U.S. like the ancient Roman Empire?

I wish we had Nero who liked the poor, wrote poems, and sang. He has gotten a lot of bad press and it’s true that he was a pathological murderer. But he was not so bad as Constantine I, who transferred the capital of the Empire from Rome to Byzantium, who poisoned, burnt, and murdered his mother, brother, and son. There were also always the Goths — the barbarian Germans from the north — who came down into the civilized Mediterranean with their gods, hatchets, and swords.

You were born and raised before television, computers, and cell phones. How have these technologies altered your way of being in the world?

I print a book in five minutes rather than have to type it and retyped it for a whole year. On the Internet, I find old films and locate old friends. Caryl Chessman – known as “The Red Light Bandit” — would not have been gassed at San Quentin in 1960 because the Supreme Court telephone was busy when his supporters called to have a stay of his execution.

What about technology for those not of your generation?

For the younger generation, technology is both good and bad. Books and literacy are in front of a firing squad. Nonetheless, I’m confident that the young are not conservative. I think they’ll even come to love Mozart and Brueghel.

You went to see the Yankee greats — Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth — play in Yankee Stadium. Are you still a Yankee fan?

Yes, but a depressed fan. Perhaps the baseball star I miss the most is Mel Ott, who played for the New York Giants for two decades and was the first National Leaguer to hit more than 500 home runs.

Are you awaiting the start of the 2013 baseball season?

Yes, but with trepidation.

When you’re in New York what do you like to do?

Stay with my childhood friend Alfred, who has a mouth like a mountain lion. I see my editor, Declan Spring, at New Directions, and Lois Conner, a great photographer, with who I went to Burma and trekked around Annapurna in Nepal. I also buy pearls and rubies wholesale and make necklaces to give to family and friends.

Americans seem to be hard on their writers — or maybe they’re hard on themselves; Jack London, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Jack Kerouac all died before they reached the age of 50 and they weren’t killed in a civil war, a revolution, or by an assassin’s bullet.

My own family is cursed. My father committed suicide and so did two brothers, though only my older brother — who designed the Rothko Chapel in Houston — was an artist. Death came early to many writers and artists and not just to Americans: Apollinaire, Modigliani, Camus, and those two twentieth-century Spanish writers, Garcia Lorca and Miguel Hernandez. Alcohol and madness have been the traditional killers. TB killed many, from Spinoza to Chopin.

I’ve always assumed you were Jewish, but Willis Barnstone doesn’t sound like a Jewish name.

My father’s original name was Bornstein. He changed it to Barnstone about 1912. As Willis Barnstone, I felt I could pass for the total White Anglo-Saxon Protestant or WASP — like Jay Gatz in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel, The Great Gatsby. Both of my parents were Jewish; a grandfather started a synagogue in Maine. My stepmother was an Argentinian Jew.

Do you celebrate Easter or Passover?

As a child I celebrated Passover with my family. Now nothing.

Would you describe your version of Heaven?

The only heaven I have is here. I only believe in now.

[Jonah Raskin, a professor emeritus at Sonoma State University and a frequent contributor to The Rag Blog, is the author of Marijuanaland: Dispatches from an American War and Rock ‘n’ Roll Women: Portraits of a Generation. Read more articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog.]