Fear and mistrust plague Iraq’s Mosul

By Tim Cocks / September 11, 2008

MOSUL, Iraq — Falah Mohammed peered over his shoulder as he spoke of how militants threatened to kill him and his family unless he quit his government job.

“It wasn’t worth the risk after the third threatening letter, so I left,” said the former guard in the northern Iraqi city of Mosul. “Insurgents have created so much fear in this place.”

Officials and security personnel die at the hands of gunmen nearly every day in Mosul, a city of 1.8 million people still struggling to shake off a determined insurgency while much of Iraq enjoys its best security in years.

Attacks in Mosul and surrounding Nineveh province have fallen since an Iraqi-led offensive against Sunni Islamist al Qaeda and other insurgents was stepped up in May. Markets are busier and traffic heavier.

But residents say a climate of fear persists in Mosul, an ancient melting pot of ethnic and sectarian groups.

“People here are very afraid,” said Nisreen Mustafa, a housewife. “We always heard explosions before the operation and we still hear them a lot now. What’s changed?”

U.S. military officials say attacks fell from around 130 per week just before the May offensive to 30 a week in Nineveh by July, before creeping up to 60-70 per week.

“It’s things like targeted drive-bys on Iraqi police,” said Major Adam Boyd, a U.S. military intelligence officer in Mosul.

“There’s a campaign of intimidation (against) … the Iraqi security forces … to get the local populace to feel insecure.”

Two weeks ago, insurgents tried to kill Major-General Riyadh Jalal Tawfiq, commander of military operations in Nineveh, with a roadside bomb. Two professors from Mosul University have been killed in the past three months.

ETHNIC PATCHWORK

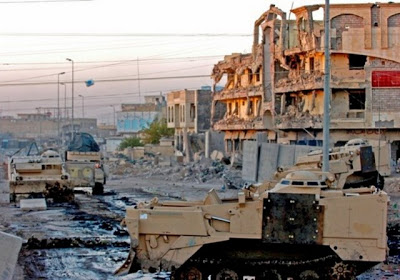

A U.S. army patrol rumbles through Mosul, past a main street so devastated by fighting that barely a building stands. Bombed out concrete roofs droop over collapsed walls. Rubble litters streets. The vehicles cross a bridge over the Tigris River and the smell of raw sewage fills the air.

But as neighbouring western Anbar province has shown, even the most violent, lawless places in Iraq can be turned around.

The desert region of Anbar was lost to insurgents in 2006, but this month the U.S. military handed control of security back to Iraqi forces after Sunni Arab tribes joined forces with the military to largely expel al Qaeda from the province.

U.S. officials do not expect Anbar’s triumph to be repeated easily in northern Iraq, where communities are a complex patchwork of Sunni and Shi’ite Arabs, Kurds, ethnic Turkmen, pre-Islamic Yazidi Kurds and Assyrian Christians.

Anbar by comparison is overwhelmingly Sunni Arab.

“The dialogue in Anbar between sheikhs willing to put aside their differences is one reason … they (succeeded),” said Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Molinari, U.S. army operations officer in Mosul.

“You don’t see that here in Nineveh. The provincial government is not open to that kind of dialogue.”

LACK OF TRUST

Mistrust between Arabs, who make up most of the police, and Kurds, who fill most army posts, hinders intelligence efforts.

In a hot, stuffy office with only one fan, U.S. Army Captain Adam Cannon greets two Iraqi army officers in their Kurdish tongue, chats, then hands them a list of suspected insurgents.

But there’s a problem, says Major Jahir Bahoddin: few in the predominantly Sunni Arab neighbourhoods will talk.

“They won’t help us,” he told Reuters. “They’d really rather not cooperate with Kurds. We are trying to tell them: ‘we’re here to rid your neighbourhood of insurgents’. Even when they want to help, they are too afraid to speak.”

Cannon said Kurdish army officers, mistrustful of Arabs, do not share information with the police. Many Kurds have bitter memories of Saddam Hussein’s oppression of Kurds in the 1980s.

Ultimately, officials say, success will depend on reviving the economy of this battered metropolis, which sprawls around the crumbling walls of the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh.

Jobless men are easily coaxed into militant groups and residents are losing patience with the pace of reconstruction.

“A lot of things need to be fixed and they’re not doing it,” said Saad Mohammed Rasheed, a former soldier in Saddam’s army who now runs a shop. “There’s no water, no electricity. We don’t hate the Americans any more; our anger is for the government.”

© Thomson Reuters 2008

Source / Reuters UK