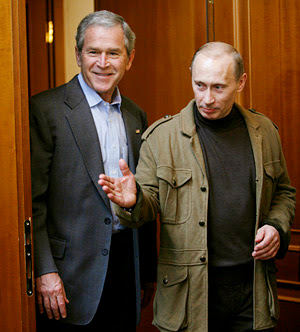

Putin’s war enablers: Bush and Cheney

By Juan Cole

Russia’s escalating war on Georgia reveals the consequences of the Bush administration’s long assault on the international rule of law.

Aug. 14, 2008 The run-up to the current chaos in the Caucasus should look quite familiar: Russia acted unilaterally rather than going through the U.N. Security Council. It used massive force against a small, weak adversary. It called for regime change in a country that had defied Moscow. It championed a separatist movement as a way of asserting dominance in a region it coveted.

Indeed, despite George W. Bush and Dick Cheney’s howls of outrage at Russian aggression in Georgia and the disputed province of South Ossetia, the Bush administration set a deep precedent for Moscow’s actions — with its own systematic assault on international law over the past seven years. Now, the administration’s condemnations of Russia ring hollow.

Bush said on Monday, responding to reports that Russia might attack the Georgian capital, “It now appears that an effort may be under way to depose [Georgia’s] duly elected government. Russia has invaded a sovereign neighboring state and threatens a democratic government elected by its people. Such an action is unacceptable in the 21st century.” By Wednesday, with more Russian troops on the move and a negotiated cease-fire quickly unraveling, Bush stepped up the rhetoric, announcing a sizable humanitarian-aid mission to Georgia and dispatching Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice to the region.

While U.S. leaders have tended to back Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili, there are two sides to every dispute, and in the ethnically diverse Caucasus it may be more like a hundred sides. Abkhazia and Ossetia are claimed by Georgia, but they have their own distinctive languages, cultures and national aspirations. Both fought for independence in the early 1990s, without success, though neither was Georgia able to assert its full sovereignty over them, accepting Russian mediation and peacekeeping troops.

The separatist leaders of South Ossetia and Abkhazia now speak of Saakashvili in terms reminiscent of the way separatists in Darfur speak of Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir. Sergei Bagapsh of Abkhazia and Eduard Kokoity of South Ossetia have come out against conducting any further talks with Georgia, calling instead for Saakashvili to be tried for war crimes. Kokoity told Interfax, “There can be no talks with the organizers of genocide.” The Russian press is full of talk of putting Saakashvili on trial for ordering attacks on Ossetian civilians.

All sides have committed massacres and behaved abominably. There are no clean hands involved, notwithstanding the strong support for Georgia visible in the press of most NATO member countries. (Georgia has been jockeying to join NATO, something Moscow stridently opposes.) Still, not everyone in NATO agrees that Saakashvili is a hero. While traveling with the negotiating team of President Nicolas Sarkozy, one French official observed that “Saakashvili was crazy enough to go in the middle of the night and bomb a city” in South Ossetia. The consequence of Russia’s riposte, he said, is “a Georgia attacked, pulverized, through its own fault.”

An emboldened Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin sarcastically likened Russia’s actions to Bush’s foreign policy. Pointing to the invasion of Iraq and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, Putin said, “Of course, Saddam Hussein ought to have been hanged for destroying several Shiite villages … And the incumbent Georgian leaders who razed 10 Ossetian villages at once, who ran over elderly people and children with tanks, who burned civilians alive in their sheds — these leaders must be taken under protection.”

In the run-up to the Iraq war, Bush officials repeated ad nauseam the mantra that Saddam Hussein had killed his own people. Thus, they helped create a case for unilateral “humanitarian intervention” of the sort Putin says Russia is now pursuing. Washington had failed to get a U.N. Security Council resolution authorizing a war on Iraq, and Iraq had not attacked the United States, so no principle of self-defense was at stake. But since all governments (even the United States under Abraham Lincoln) repress separatist movements, often ruthlessly, Bush was turning actions such as Saakashvili’s attack on South Ossetia into a more legitimate cause for an outside power (especially one bordering it) to wage war against Georgia.

Indeed, Putin’s invoking Bush’s Iraq adventure points directly to the way in which Bush has enabled other world powers to act impulsively. With his doctrine of preemptive warfare, Bush single-handedly tore down the architecture of post-World War II international law erected by the founders of the United Nations to ensure that rogue states did not go about launching wars of aggression the way Hitler had. While safeguarding minorities at risk is a praiseworthy goal, the U.N. Charter states that the Security Council must approve a war launched for this purpose or any other, excepting self-defense. No individual nation is authorized to wage aggressive war on a vigilante basis, as Bush did in Iraq or Russia is now doing in the Caucasus.

Eight years ago, the United States would have been in a position to condemn Russia for its unilateral war without necessarily seeming hypocritical. After all, even the Korean War had been sanctioned by the United Nations, and President Dwight Eisenhower had condemned the 1956 tripartite attack on Egypt by Britain, France and Israel for violating the U.N. Charter.

Bush’s recent argument, that a democratically elected government should not be overthrown (no matter what its behavior, apparently), was intended to sidestep comparisons between his own unilateral wars of aggression and ones such as the current Russian intervention. He was implying that his invasion of Iraq toppled a government that lacked the legitimacy enjoyed by Saakashvili’s.

In fact, Bush’s foreign policy includes a long list of actions intended to undermine elected governments.

Whether the United States was actively involved in the attempted coup in 2002 against Hugo Chavez, the democratically elected president of Venezuela, or merely cheered it on, it is clear that Venezuelan popular sovereignty meant nothing to Bush if it resulted in a government unfriendly to and critical of Washington.

An even more egregious example came with the destabilization and overthrow of the Hamas government, which won control of the Palestine Authority in January 2006. Bush insisted on allowing the participation in elections of Hamas, a fundamentalist party with a covert paramilitary that has struck at Israeli targets, including civilians. When the party unexpectedly won, however, Bush refused to recognize the legitimacy of the new government, denying it funds and sympathizing with the Israeli attempt to overthrow it. Israeli security forces kidnapped elected Hamas representatives and cabinet ministers, and harmed civilians by blocking medical aid and food that might go to people via the Hamas government.

In 2007, Bush and the Israelis supported a takeover in the West Bank by forces of the Palestine Liberation Organization, lead by Palestine Authority President Mahmoud Abbas. Similar attempts were made in Gaza, but they failed, leaving the elected Hamas government in charge of the small territory. Palestinian popular sovereignty, and Hamas’ victory in what were widely judged to have been relatively free and fair elections, were disregarded by Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert and Bush.

Bush and Cheney also repeatedly sided with military dictator Pervez Musharraf against elected civilian politicians in Pakistan. Even when the Pakistani Parliament, elected in open polls last February, initiated impeachment proceedings against Musharraf earlier this week, the Bush administration came out against the idea of Musharraf’s going into exile if convicted, urging that he be allowed to stay “honorably” in Pakistan if he stepped down.

Bush’s exceptionalism, whereby he implicitly maintained that no international laws or institutions would be allowed to constrain U.S. actions taken in the name of national security, grew out of the sole superpower status of the United States after fall of the Soviet Union. A unipolar world is, however, an exceedingly rare circumstance in modern world history, and it was unlikely to last very long. China may soon have the economic and technological clout to go toe to toe with the United States; and Russia, fueled by the energy boom, is recovering from its economic disaster of the 1990s.

The collapse of the Soviet economy produced tremendous misery and downward mobility. Uncertainty made couples unwilling to risk having children. In one of the great demographic reversals in history, the Russian Federation’s population fell by 10 million in the years after 1991. Russian need for U.S. foreign aid and goodwill led Moscow to acquiesce for a time in the expansion of U.S. influence into Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

Russia is now reemerging and flexing its muscles. The run-up in the price of oil and gas has filled Moscow’s coffers, since it is one of the great producers of natural gas in the world (prices of natural gas tend to track with those of petroleum). Russia has reasserted its influence in countries such as Uzbekistan, which had briefly licensed a base to U.S. forces but then kicked them out, and in Turkmenistan, which recently agreed to pipe its natural gas through Moscow. Russian President Dmitri Medvedev and Prime Minister Putin are increasingly acting like Gulf emirs, flush with petrodollars and assured of political leverage because of their control over energy resources.

In a unipolar world, the Bush doctrine of preemptive war allowed Washington to assert itself without fear of contradiction. The Bush doctrine, however, was never meant to be emulated by others and was therefore implicitly predicated on the notion that all challengers would be weaker than the United States throughout the 21st century. Bush and Cheney are now getting a glimpse of a multipolar world in which other powers can adopt their modus operandi with impunity. Bush’s rhetoric may have sounded like that of President Woodrow Wilson, but his policy has often been to support the overthrow or hobbling of elected governments that he does not like — and that has not gone unnoticed by countries that also count themselves great powers and would not mind following suit.

The problem with international law for a superpower is that it is a constraint on overweening ambition. Its virtue is that it constrains the aggressive ambitions of others. Bush gutted it because he thought the United States would not need it anytime soon. But Russia is now demonstrating that the Bush doctrine can just as easily be the Putin doctrine. And that leaves America less secure in a world of vigilante powers that spout rhetoric about high ideals to justify their unchecked military interventions. It is the world that Bush has helped build.

Source / Salon