Three human beings, who have given my own life color and joy, are gone now, fallen like leaves from deciduous branches.

My brother died last year. He was a gentle soul, devoid of personal ambition. He led a quiet life, leaving few footprints. When he could, he assisted people who sought his help. When he was no longer financially or physically able, none of those he helped came to his aid, but others did. His friends supported him lovingly, just because he needed it. Their generosity illuminated his final days. When those friends and I have passed on, all memory of my brother will disappear. Then he will be truly dead.

My friend Bill died eight years ago at age 60. It was amazing he lived so long because at nineteen he broke his neck. After two years in the hospital, he spent the rest of his life in a wheelchair. From his mid-chest downward, his body was numb, useless flesh. He had limited use of his arms and couldn’t make a fist.

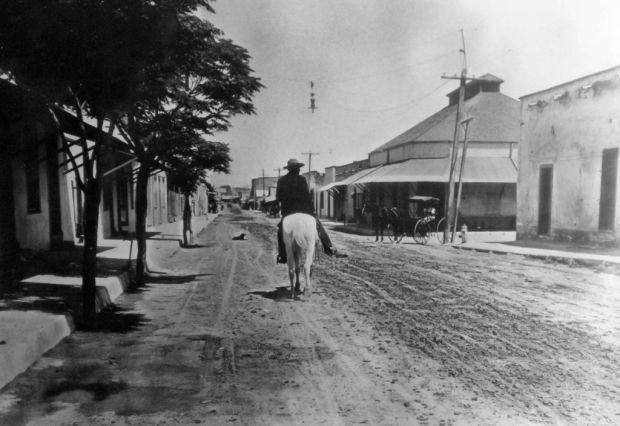

Though Bill suffered numerous hospitalizations, he did not live as an invalid. He got himself around, drove long distances, and loved a good time. I met him in the 1970s in a funky Mexican beach town well off the map of most able-bodied Americans. One time we lifted his chair into a long wooden skiff with an outboard motor and took off for islands several hours off the coast. If he had fallen into the sea, he knew we couldn’t have saved him. Bill’s transcendent spirit is gone now, soon to be forgotten.

My friend Oscar died last summer, after 40-odd years of lobster fishing.

My friend Oscar died last summer, after 40-odd years of lobster fishing. He worked himself to death doing what he loved. He was born to the lobstering life, but rebelled in his teens and roved around the country. In his twenties he concluded that following his family tradition was what he loved best. He defended that independent way of life against encroaching regulations, pollution, and competition, becoming an exemplary professional.

His colleagues chose him to represent them to the state and federal governments year after year. Members of the lobstering community he served will preserve his memory until they too die off. Then all knowledge of Oscar’s virtuosic competence, his eclectic musical and literary tastes, his wicked wit and booming laughter, will vanish from the earth.

What is a life, anyway? What does it signify? These three individuals, among others, are touchstones of my own existence, endowing it with pleasure and meaning. My love for them helps to locate and define me. Their voices and laughter echo in my soul. But I too shall soon pass away, along with all their friends and families. After a generation or so, no one who ever knew me will remain.

Millions of us come and go all the time. A few iconic names and faces remain preserved in cultural or political memory. Most of us live unknown and die forgotten. The lives we touch for better or worse will also disappear, as if we and they had never existed. So what does it all mean?

Of all the life forms, only human beings look for reasons.

Of all the life forms, only human beings look for reasons. Because we know we are destined to die, we invent religions to console us with omniscient deities and elaborate afterlives. To distract ourselves from our mortality we overdose on booze or dope or work, numbing our senses, happy to sacrifice our awareness to evade our fear. We cultivate habits that dull the wonder of our days. As if we had all the time in the world.

Some of us are lazy or unconfident enough to let others define our agendas and even our values. Many feel lost or unworthy. Some seek surrogate satisfaction in the lives of celebrities. Or sports teams. Others can only value themselves by denigrating entire classes of people for reasons of race, gender, nationality, religion, or some other trait. The curse of categorical thinking. Many see the human race as a competition. It’s enough to make you cry. Or laugh. The challenge is to hear our own hearts.

Is a dot-com billionaire more important than a maple leaf that dies in autumn and falls to the ground? The mogul has agency, a capacity for good or evil, but does not possess any more inherent significance than plant life. And the leaf is arguably more aesthetically pleasing than the financier, especially in its penultimate autumnal splendor. Of course, the billionaire will also wither and die.

My brother found his purpose by helping others.

My brother found his purpose by helping others, taking little thought for his own material comforts. After his wife died he downsized drastically and gave away most of what he owned. He spent his last years in a tiny apartment, living an ascetic, almost monk-like existence. But instead of religion, he turned to ESPN and card games with other retirees.

My paraplegic friend Bill loved to party. But he also embraced Transcendental Meditation, basking in the stillness and freedom beyond the limitations of time and damaged flesh. He took comfort and strength from those forays into the eternal space that is our source and our destination.

Like all true sailors, Oscar was happiest at sea, entering into the natural rhythms of the winds and tides. He loved being part of the cosmic process, intimately connected to the elemental world. He worked year round, rising before dawn in all weathers. He always maintained his boat and the harbor under his jurisdiction in good order out of respect for the privilege of living his chosen life.

These three human beings, who have given my own life color and joy, are gone now, fallen like leaves from deciduous branches. More than a sense of loss I feel an abiding gratitude for our friendships and our time together. That feeling will die with me, of course, but perhaps I can pass some ephemeral energy on to others, before they too achieve oblivion. Like footprints in the sand along the tide line. It’s — we’re — all so fleeting, now here, now gone.

Read more of James McEnteer’s articles on The Rag Blog.

[Rag Blog contributor James McEnteer is the author of Shooting the Truth: the Rise of American Political Documentaries (Praeger). He lives in Quito, Ecuador.]