Part II

Who Watches the Watchman?

COINTELPRO and the Federal Government’s

Clandestine Attack on the U.S. Constitution

By James Retherford / The Rag Blog / June 30, 2009

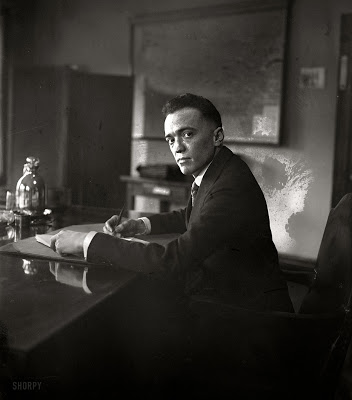

The repression of dissident groups by shadowy government operatives is nothing new in America. In fact, starting with John Ashcroft, Bush administration attorneys general and their declared nostalgia for the good old days of COINTELPRO resonate with the ideology of another attorney general who left behind an authoritarian legacy more than eighty five years ago — A. Mitchell Palmer.

[A version of this series was originally researched and written six years ago. It describes in chilling detail how the U.S. government surreptitiously conspired to maintain lockdown social control of American citizens in the period up to and including post-Watergate. Go here for the introduction to and Part I of “Who Watches the Watchman.”]

In 1920 the bureau, headed by a youthful and enthusiastic new director named J. Edgar Hoover, carried out the infamous “Palmer Raids” — 10,000 persons were rounded up in thirty-three cities, resulting in “indiscriminate arrests of the innocent with the guilty, unlawful seizures by federal detectives…,” and other violations of constitutional rights.

The Church Committee quoted the conclusions of a group of distinguished legal scholars who investigated the Palmer raids and “found federal agents guilty of using third-degree tortures, making illegal searches and arrests, using agents provocateurs….” Attorney General Palmer justified his actions “to clean up the country almost unaided by any virile legislation” on grounds that Congress had failed to act “to stamp out these seditious societies in their open defiance of law by various forms of propaganda.” His avowed purpose was “to tear out the radical seeds that have entangled American ideas in their poisonous theories.”

An early FBI target — and clear precedent for later COINTELPRO practice — was Marcus Garvey, founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association. Under his leadership, UNIA, which to this day remains the largest organization of African Americans ever assembled, devoted itself to “bootstrapping” strategies (i.e., undertaking business ventures as a means of attaining its goals of black pride and self-sufficiency).

Despite UNIA’s explicitly capitalist orientation — or maybe because of it — Hoover launched an inquiry into Garvey’s activities in August 1919. When this initial probe revealed no tangible evidence of wrongdoing, Hoover, still railing against Garvey’s “pro-Negroism,” ordered that the investigation be not only continued but intensified. Still, it was another two years before the bureau was able to find a pretext — Garvey’s technical violation of laws governing corporate stock offerings — upon which to bring charges of mail fraud. Convicted in July 1923 by an all-white jury, the UNIA leader was first incarcerated in the federal prison at Atlanta, then deported as an undesirable alien in 1927. By then, his organization had disintegrated, and Hoover vowed to prevent anyone from ever again assuming the standing of what he called a “Negro Moses.”

World War II brought a return of the FBI to counterintelligence operations as President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued a series of instructions establishing the basic domestic intelligence structure for the federal government. Roosevelt was advised by Hoover to proceed with the utmost degree of secrecy:

In considering the steps to be taken for the expansion of the present structure of Intelligence work, it is believed imperative that it proceed with the utmost degree of secrecy in order to avoid criticism or objections which might be raised to such an expansion by either ill-informed persons or individuals having some ulterior motive … Consequently, it would seem undesirable to seek any special legislation which would draw attention to the fact that it was proposed to develop a special counterespionage drive of any great magnitude.

According to William C. Sullivan, Hoover’s assistant for many years:

Such a very great man as Franklin D. Roosevelt saw nothing wrong in asking the FBI to investigate those opposing his lend-lease policy — a purely political request. He also had us look into the activities of others who opposed our entrance into World War II, just as later Administrations had the FBI look into those opposing the conflict in Vietnam. It was a political request also when he [Roosevelt] instructed us to put a telephone tap, a microphone, and a physical surveillance on an internationally known leader in his Administration. It was done. The results he wanted were secured and given to him. Certain records of this kind… were not then or later put into the regular FBI filing system. Rather, they were deliberately kept out of it.

The 1940 passage of the Smith Act made “sedition” a peacetime, as well as a wartime, offense. The doctrine was laid out by Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson in his opinion upholding of the Smith Act on the grounds “that it was no violation of free speech to convict Communists for conspiring to teach or advocate the forcible overthrow of the government, even if no clear and present danger could be proved.” For if the clear and present danger test were applied, Jackson argued, “it means that Communist plotting is protected during its period of incubation; if preliminary stages of organization and preparation are immune from the law, the Government can move only after imminent action is manifest, when it would, of course, be too late.” Thus there must be “some legal formula that will secure an existing order against revolutionary radicalism.”

Hoover claimed that by 1940 “advocates of foreign isms” had succeeded in burrowing into every phase of American life, masquerading behind various front organizations. In 1939, Hoover told the House Appropriations Committee that his General Intelligence Division had “compiled extensive indices of individuals, groups, and organizations engaged in subversive activities, in espionage activities, or any activities that are possibly detrimental to the internal security of the United States… Their backgrounds and activities are known to the Bureau. These indexes will be extremely important and valuable in a grave emergency.”

After World War II, the FBI’s attention turned from fascism to communism, marking the beginning of the Cold War. In March 1946, Hoover informed Attorney General Tom Clark that the FBI had

found it necessary to intensify its investigation of Communist party activities and Soviet espionage cases and it was taking steps to list all members of the Communist party and any others who might be dangerous in the event of a break with the Soviet Union, or other serious crisis involving the United States and the USSR. It might be necessary in a crisis to immediately detain a large number of American citizens.

As for the Communist party, “ordinary conspiracy principles” sufficed to charge any individual associated with it “with responsibility for and participation in all that makes up the Party’s program” and “even an individual,” acting alone and apart from any “conspiracy,” “cannot claim that the Constitution protects him in advocating or teaching overthrow of government by force or violence.”

In 1948, the Mundt-Nixon bill, calling for the registration of the Communist party, was reported out of Richard M. Nixon’s House Committee on Un-American Activities. Senate liberals objected. After Truman’s veto they proposed a substitute — “the ultimate weapon of repression: concentration camps to intern potential troublemakers on the occasion of some loosely defined future ‘Internal Security Emergency.’”

This substitute was advocated by Senator Hubert Humphrey, then a freshman lawmaker. Humphrey later voted against the bill, though not because he had a chance to reconsider his concentration camp proposal but rather because he was concerned that the conference committee had brought back “a weaker bill, not a bill to strike stronger blows at the Communist menace, but weaker blows.” The problem with the new bill was that those interned in the detention centers would have “the right of habeas corpus so they can be released and go on to do their dirty business.”

Thus when the first formal COINTELPRO was launched against the U.S. Communist Party in 1956, it may have been the first instance in which an internal security agency was instructed to employ the full range of extralegal techniques developed by the bureau’s counterintelligence specialists against a domestic target in a centrally coordinated and programmatic way, but in reality the FBI had conducted such operations on an ad hoc basis against the CPUSA and to a lesser extent the Socialist Workers Party since at least 1941.

[James Retherford knows firsthand what it was like to be targeted by COINTELPRO. A founder and editor of The Spectator in Bloomington, Indiana, in 1966, Retherford is a director of the New Journalism Project, the nonprofit organization that publishes The Rag Blog.]

Please see

- James Retherford: Who Watches the Watchman?, Introduction,

- James Retherford: Who Watches the Watchman? J. Edgar Hoover and COINTELPRO, Part I.

and

Also see James Retherford : Brandon Darby, The Texas 2, and the FBI’s Runaway Informants by James Retherford / The Rag Blog / May 26, 2009

And for more background on the history of informants in Texas, read The Spies of Texas by Thorne Dreyer / The Texas Observer / Nov. 17, 2006.

Jim — I begin to see the broader outline of this series and am absolutely struck with admiration — bravo! I know someone you should talk with.

Please credit my (copyrighted) illustration of "The Palmer Raids" (done for the calendar of the Progressive, but still mine, legally)…

Lisa Haney

http://www.lisahaney.com

This will not have effect as a matter of fact, that’s what I suppose.