Aretha Franklin producer, Atlantic Records co-chief and music business pioneer dies at age 91

By Ashley Kahn / August 15, 2008

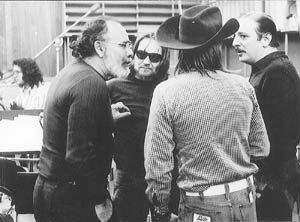

See ‘Wexler worked with Austin musicians like Willie Nelson…’ below.

Jerry Wexler, the legendary record man, music producer and ageless hipster, died at 3:45 a.m. August 15 at the age of 91. Wexler was one of the great music business pioneers of the 20th century: as co-head of Atlantic Records from 1953 to ’75, he and his partner Ahmet Ertegun grew the small independent R&B label into the major record company that it is today.

Wexler was much more than a top executive — he was a national tastemaker and a prophet of roots and rhythm. The impact of his deeds matched his larger-than-life personality. Because of him, we use the term “rhythm and blues” and we hail Ray Charles as “Genius” and Aretha Franklin as “Queen.” We came to know of a record label called Stax and a small town called Muscle Shoals, Alabama. We witnessed the rise of Led Zeppelin and the Allman Brothers, and we care about a thing called soul.

In the ’50s, Wexler’s studio work helped introduce white ears to the royalty of R&B: Ray Charles, Big Joe Turner, the Drifters, LaVern Baker, Chuck Willis. In the ’60s as the age of R&B gave way to the rock and soul era, Wexler and Ertegun steered Atlantic into a lead position among labels, releasing music by Otis Redding and Aretha Franklin, Cream and Led Zeppelin, Solomon Burke and Wilson Pickett, Duane Allman, and Willie Nelson. In the ’70s, Wexler departed Atlantic and went freelance, producing soundtracks for films by Louis Malle and Richard Pryor, and recording albums with Bob Dylan, Dire Straits, and Etta James and others.

Wexler was a throwback to a time when record men could be found in the studio and the office, producing the music and running the company. Blessed with big ears — they really were large — his productions generated a staggering number of gold and platinum records. The collective impact of the music he personally produced or somehow ushered into being won him nearly every lifetime honor in the music world.

In 1987, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, one of the first non-performers to receive the honor. Tuxedoed and hale, he summed up his work at Atlantic: “We were making rhythm and blues music — black music by black musicians for black adult buyers perpetrated by white Jewish and Turkish entrepreneurs.”

Laughing, Wexler added, “Incidentally, two weeks ago I hit three score and 10 — the Biblical allotment. So this is my first posthumous award.”

He was born Gerald Wexler in 1917 to a working class family, and grew up during the Depression in the upper Manhattan neighborhood of Washington Heights. His youth was marked by poolrooms and truancy, until the mid-1930s when he was distracted by a music called jazz. Wexler became part of a loosely knit group of record collectors and streetwise intellectuals, praising trumpeter Henry “Red” Allen and quoting Spinoza. Many members of this circle eventually became captains of the music industry: John Hammond and George Avakian at Columbia Records, Milt Gabler and Bob Thiele at Decca, Alfred Lion and Frank Wolff at Blue Note, and Wexler’s future partners at Atlantic, Ahmet and Nesuhi Ertegun.

“If somebody asked me who I was,” Wexler said, “an aspiring journalist, a stick ball player from Washington Heights, the son of a window cleaner? No, I was a record collector. And we all felt that way.

“We were absolutely a cult. It was ‘we happy few’ as the English say. We used to hang out at the Commodore Record Shop, this little in-group, and get together in the evening. We loved McSorley’s Ale and maybe we’d smoke a cigarette without any name on it. People would bring their favorite records and we’d be listening to Louis and his Hot Five, Hot Seven, whatever.”

A mother who was convinced she had birthed the next Faulkner, and a Stateside stint in the Army during WWII (spent partly in Miami) helped steer Wexler down a more accomplished path. He attended college in Kansas upon being discharged, and in 1946 returned to New York to pursue a career in journalism and the music business. In a day when music publishers held more power than record companies, he first worked as a song-plugger, and then as a Billboard reporter. In 1949, he coined the term “Rhythm and Blues” for the magazine’s black music chart to replace the term “Race Music.”

Wexler was the wordsmith, and revered and respected his favorite authors — Hemingway, Fitzgerald, James M. Cain and John O’Hara — as he did his favorite jazz and bluesmen. Praising a Big Joe Turner big band album, he wrote that it had been created sub specie aeternitatis. Look it up — the Latin and the album.

Ertegun thought and felt the same way. They became friends and in 1953, when he asked Wexler to join Atlantic Records, partners as well. It was a gesture Wexler never forgot. “In a way,” he said after Ertegun’s death in 2006, “he handed me a life.”

Wexler’s first years at Atlantic found him recording the music that built the foundation of rock — songs about partying, romancing and one about shaking, rattling and rolling, that really had more to do with what happened in car backseats than in the kitchen. Some went further: Clyde McPhatter’s “Honey Love” (banned by some radio stations for indecency) and the Clovers’ “Down in the Alley” (“I’ll plant you now and dig you later/Because you’re my sweet potato”) were a refreshing poke at the propriety of the ’50s.

For Wexler, it was on-the-job training: “No one really knew how to make a record when I started. You simply went into the studio, turned on the mike and said play.” Atlantic’s forte was a sound that was clear, precise, and heavy on the groove — the label was one of the first to mike the rhythm section separately. “My rubric [for the sound] was ‘Immaculate Funk,’ ” he wrote in his autobiography Rhythm and the Blues (a must-read for anyone seeking a handle on how American music came to be).

When most radio stations were playing Perry Como and Doris Day, Wexler pleaded, cajoled, bullied and even paid to get airplay for the latest Atlantic singles.

Everyone — black and white — was listening. As Ertegun once put it, “they could segregate everything else, but they couldn’t segregate the radio dial.”

With Ertegun sitting one desk away in their small office on Manhattan’s West 56th Street, Wexler fought a righteous fight: hassling distributors for payment, battling other labels for market share, at times getting what was needed by sheer force of personality. He was no angel — he could be imperious and had a reputation for unusually erudite, red-faced rants.

Working together, the two made a formidable pair, balancing their love of music and music-makers with their will to survive. “Wexler and Ertegun could be ruthless opportunists on one hand and enormously generous on the other,” says Jerry Leiber, who would know. He was one half of Leiber and Stoller, the famous songwriting/production team that provided Atlantic an unbroken string of hit recordings by the Coasters, the Drifters and Ben E. King.

Wexler increased Atlantic’s fortune by forging innovative contracts with songwriters, producers, labels and studios — many have since become common practice in the industry. In 1957, he brought Leiber and Stoller to New York from the West Coast and structured a distribution deal allowing them to work as independent A&R men for the label. Similar arrangements with upstart producers Phil Spector and Bert Berns followed.

Wexler initiated another specialty in the early ’60s: launching subsidiary labels under the Atlantic umbrella (Rolling Stone Records, and Led Zeppelin’s Swan Song, Capricorn Records, home to the Allman Brothers, were three hugely profitable imprints made possible by his innovation). At the close of the decade, Wexler flew British songbird Dusty Springfield to Memphis to record an album that stands as her career best. To secure her signing with Atlantic, Wexler agreed to personally produce the session: a precursor to the ubiquitous “key-man” clause in today’s contracts.

In Memphis, Wexler discovered Stax Records and developed a distribution deal that brought to Atlantic the brightest stars of Southern soul: Rufus and Carla Thomas, Booker T. & the MGs, Otis Redding. At Stax, and in a few studios in nearby Muscle Shoals, Wexler learned a new way of making records: more organic and improvised than the pressured, pre-written approach typical of New York City studios. He was soon bringing Atlantic artists south to record; Wilson Pickett, Don Covay and Sam & Dave were among the many to benefit from Wexler’s change of venue.

The stage was set for what today stands as Wexler’s greatest single triumph. In 1966, he signed a singer whose Columbia Records contract had lapsed, and whose potential had yet to be realized. Wexler asked Aretha Franklin to drop the Judy Garland cabaret act, play the piano herself and focus on her natural, church-trained way of singing. Before one could spell “respect,” a legend was born, and a new way of singing became the standard — it’s impossible to imagine Whitney, Mariah or Christina today without Aretha. More significantly, Franklin’s ascendancy marked a seismic cultural shift: What black America was listening to — in its full unbleached form — became a significant and permanent part of the popular playlist.

By the late ’60s, Atlantic’s legacy proved to be a dividend as many British rock groups chose to be on the same label as their R&B and soul heroes. Cream, Yes, King Crimson, the Bee Gees, Emerson, Lake and Palmer all signed to Atlantic. On a tip from Dusty, Wexler signed Led Zeppelin, crafting a contract that allowed the band to produce themselves. Blown away by a young electric slide guitar player in Muscle Shoals, he bought out Duane Allman’s studio contract, effectively releasing him to form the Allman Brothers. He signed Southern gospel-tinged rockers Delaney and Bonnie, and the proto-metal band Vanilla Fudge.

Not every move was a good one. In 1968, Wexler convinced the Ertegun brothers to sell Atlantic to Warner Brothers (then known as Warner Seven Arts) but left major money on the table. Wexler regretted the decision the rest of his life. “What a mistake. Worst thing we ever did. It was because of my own insecurity when I saw all these other independent record companies going out of existence. We were sort of done in by the broker who was supposed to be representing us. He undersold us.”

Generous contracts notwithstanding, the three partners became employees for the first time, answering to a board of directors. For Wexler it was a rough fit. The irony is that Ertegun, who resisted going corporate, eventually thrived in that environment, his diplomatic pedigree helping him navigate boardroom culture.

The move did liberate Wexler from the overriding concern with the company’s bottom line. As he had when he first arrived at Atlantic, he focused on the music he wanted to hear. Noticing a new blend of Southern rock, country and R&B he dubbed “Swamp,” he produced sessions for the likes of Ronnie Hawkins, Donnie Fritts and Tony Joe White. Some soul productions — like Donny Hathaway — fared well saleswise; others did not. “The two albums I’m proudest of are Dr. John’s Gumbo and Doug Sahm and Band. And they both tanked. Two of Atlantic’s worst sellers.”

In 1974, Wexler led a failed attempt to establish Atlantic in Nashville; two classic albums that paired him with Willie Nelson were the most that came from the effort.

In 1975, Wexler departed Atlantic and — save for a brief run heading East Coast A&R for Warner Bros. where he signed the B-52s and the Gang of Four — he freelanced for the remainder of his career, producing albums for Bob Dylan, Dire Straits, Etta James, Allen Toussaint, the Staple Singers, George Michael, Jose Feliciano, Linda Ronstadt and Carlos Santana.

In the late ’90s, Wexler retired to his Florida home and canceled his Billboard subscription, disengaging himself from the music business. While Ertegun remained an industry fixture atop Atlantic, Wexler was visited by a steady stream of journalists and TV crews wanting to talk about the past. He could be irascible at times, but he wasn’t turning them away.

“They keep coming time and again and I do them and sometimes they’re good. Well they’re never really bad because they’re dealing with state of the art here in an interview — not everybody can deliver a paragraph extemporaneously,” Wexler laughed. “More hubris.”

This reporter visited Wexler in his Sarasota, Florida home over a year ago: We spent a long afternoon in his living room, surrounded by photographs of him smiling with Ray, Willie, Bob, Aretha and the Muscle Shoals rhythm section. At 89, he was energetic and totally unenthused at the idea of turning 90. He was happy to speak of the Atlantic years, and dismissive of his and Ahmet’s portrayal in the Ray movie (“Two stick figures, empty suits? That’s not who we were. But it had to be seen for two reasons — the music and Jamie Foxx.”). He lit up when talking of early jazz heroes like trumpeter Henry “Red” Allen and saxophonist Bud Freeman, and at one point broke into a verse from an obscure 1926 song: “I want a big butter and egg man/Don’t some butter and egg man want me?”

Jerry Wexler died peacefully, and leaves behind his wife, the novelist Jean Arnold, his children Paul and Lisa, and an undying legacy. Less than two weeks before he died, he was still taking calls. “Always answer the phone,” was a personal motto of his. “You never know if it’s a hit calling.”

Source / Rollingstone.com

An arrangement was needed for ‘Bubbles in My Beer,’ and Mardin (r), Wexler (l), Willie, and Sahm talked about it . Photo By David Gahr / Austin Chronicle.

Wexler worked with Austin musicians like Willie Nelson, Doug Sahm, Marcia Ball and Lou Ann Barton

In the studio, Wexler “knew what he wanted, and he got what he wanted,” Augie Meyers, who was [Doug] Sahm’s keyboard player, said Friday. Wexler picked up Sahm’s contract from Mercury Records, producing and releasing the Texas music landmark album “Doug Sahm and Band” in 1973. …In the 1970s, he welcomed Willie Nelson to Atlantic, where he released “Shotgun Willie” in 1973 and “Phases and Stages” in ’74, the albums that began what we now think of as Nelson’s classic “outlaw” period (most of which was recorded for Columbia).

Nelson’s publicist said he had not commented on Wexler’s passing.

In 1972, Wexler produced an album by Austin’s Freda & the Firedogs, a band that included Bobby Earl Smith and a young Marcia Ball. A mix of country, folk and blues, the record was shelved when the band balked at signing with Atlantic.

“Meeting Wexler was one of those events that really made a huge difference in my life,” Smith said Friday. “He stuck his neck way out for what was happening in Austin.”

In 1999, when Smith and Ball decided to issue the Firedogs record themselves, Smith was forced to call Wexler for the masters.

“He said the masters burned in a fire,” Smith said. “But he gave us his personal copy. His generosity in just giving me the tapes when we had strung him along when he was sticking his neck out for us was just a boon. I really didn’t have words to thank him.”

In 1980, Wexler offered to produce a record by Fort Worth native Lou Ann Barton after seeing her in a New York club. The result, “Old Enough,” was released on Asylum in 1982 and launched her onto the national stage. Wexler visited Austin to help promote her when she was a frequent act at Antone’s.

Joe Gross / Austin American- Statesman / Austin360