Defending the Movement:

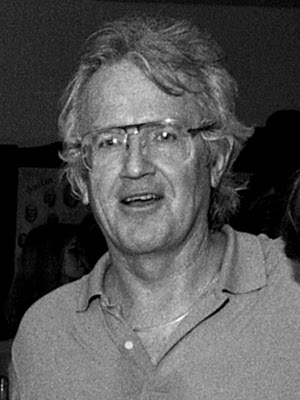

Remembering Cam Cunningham

In 1971 we cleaned out our firm bank account and took off by car to the May Day action in Washington, D.C., where we started out as participants… to ‘shut down D.C.’ in protest against the Vietnam war and wound up lawyering to get our comrades out of jail.

By Jim Simons | The Rag Blog | July 15, 2012

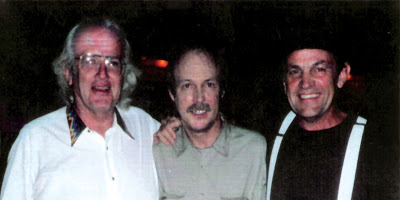

Jim Simons will join his former Movement law partner Brady Coleman (now an actor and musician) and Brady’s band, The Melancholy Ramblers (who will perform live) as Thorne Dreyer‘s guests on Rag Radio, Friday, July 27, 2-3 p.m., on KOOP 91.7-FM in Austin, and streamed live on the Internet.

AUSTIN — Cameron McPherson Cunningham was a lawyer nonpareil. Although he succumbed to cancer in July 2012, he will be long remembered in Texas and California, even on the national stage, because he chose to be a lawyer for the people, not for the corporations.

It is not so uncommon now for young lawyers to go into public interest law, or legal services, or even to become radical lawyers, as Bill Kunstler described himself in his memoir. When I was Cam’s law partner for the early years in Austin — 1969 to 1978 — we both thought of ourselves and self-identified as radical lawyers. As did other partners who came aboard the rollicking ship of our law firm, unlike most all the legal vessels of the time. We meant it to be that way. And I can tell you it was damn good fun in addition to being deadly serious politics.

It all started in Montreat, North Carlolina, in late August or early September 1969. Cam had graduated from the University of Texas Law School in 1967. He received a Reginald Heber Smith fellowship which paid all or part of his salary at a designated legal services program. For him it was the DNA Navajo legal services program, federally funded as part of the War on Poverty, located in the four corners in Arizona. DNA is an acronym for the Navajo phrase Dinébe’iiná Náhiitna be Agha’diit’ahii — which means “attorneys who work for the economic revitalization of The People.”

I had met Cam when he was still in law school and I was with the OEO Regional Office in Austin. (OEO being the federal agency that ran the War on Poverty). Over the next couple of years we became friends. The Movement had galvanized a large segment of young people in the U.S. I opened my solo practice in 1968 and was immediately swamped with cases arising from anti-war demonstrations, the military draft, and civil rights.

In December of 1968 Austin activists, including Martin Wiginton and Greg Calvert, with input from Cam in Arizona, organized a conference of lawyers and Movement people at a dude ranch in Wimberley, Texas, just outside of Austin. The purpose was to nudge fee-charging lawyers into pro bono representation of the multitude of arrestees and military resisters.

As a result of the conference, Cam was “hired” as a roving organizer or liaison with the progressively-inclined lawyers in Texas identified at Wimberley. I doubt that much money for living expenses was ever paid but at some point Cam left the legal services program to take on his new task.

He and his wife, Cris, moved into the rented house where my wife and I lived on the east side of Austin. We became closer friends, so to speak. But we did enjoy the companionship and it was the Sixties. I recall that Cam got a part-time position at the law school with the penal code revision project, in part thanks to law professor and friend, Fred Cohen, known facetiously by other faculty folk as “Fred the Red.”

By 1969 Cam was committed to devoting his considerable energies and abilities to Movement law. At summer’s end we got wind of the lawyers’ confab known as the Southern Legal Action Movement (SLAM) to be held at Black Mountain near Montreat, North Carolina. Cam convinced me to go although I had been in informal rehab from the law that summer.

Like Wimberley, the Montreat conference was wild and wooly. All the Movement lawyers we ever heard of were there. From the New York Law Commune we found a model for what Cam wanted to do in Austin: a law commune. And so it was born in the wee hours one night in a long whiskey conversation between the two of us. He had the vision and I at least had some experience in such cases, which did not make me enthusiastic at first. We followed the New York lawyers up to New York after the conference and learned a lot.

Those idealistic principles seem a tad naive now. Like income limitation, legal workers and lawyers all with the same say and voice in the operation, fee cases to pay the way for Movement work, and so on. By the time we got back to Austin I did share Cam’s zeal to proceed with it; he had won me over. We rented a small suite near the University of Texas campus. We had one legal worker, Julie Howell (she is a lawyer now). But it really did not go too well.

Cam was trying to keep the penal code revision job and still practice law. We did defend Richard Chasein at a general court-martial at Fort Hood, after he declined training for riot control in American cities. This was a Movement case we did without fees. Other cases that should have generated fees didn’t. Money was a big problem that fall. I took a job at Dallas Legal Services Project in the spring of 1970. Cam soldiered on. In a few months I returned.

That summer the Radical Lawyers Caucus was formed for a run at the State Bar of Texas convention. With Bill Kunstler as our main speaker and other speeches by Maury Maverick, Jr. and Warren Burnett — both great progressive Texas lawyers — we made a splash at the convention. Before the convention the bar’s official journal declined to accept our paid ad about the Radical Lawyers Caucus. The suit we wanted to file was sent to Cam in Austin. I came back in time to brief the law and try the case which we won in federal court.

Our early struggles, stops and starts, changed for the better when a trial lawyer from East Texas contacted us — or we contacted him after we saw his ad in the Texas Observer. In the fall of 1970 Brady Coleman became the third musketeer and our course was set. For the next couple of years we three were very close. We joked that we were closer to each other than to our wives, which was probably no joke. All three marriages ended in divorce in the early ‘70s.

Brady had a lot of trial experience and he and Cam became a lethal trial team. Cases all around the state sent us into battle: Dallas, Houston, South Texas, and West Texas. Fort Hood kept us hopping. Busts on a large scale happened around the university. Cam was loving the practice of Movement law. He especially took to the criminal law. He and I defended a black activist charged with setting the UT ROTC building on fire.

Cam and Brady tried some murder cases (not political) and we all represented those charged with drugs. Brady and I tried civil cases against the city, police, even one against Ma Bell, the proceeds of which funded a great party that we dubbed the Last Annual Ma Bell Counter-Ripoff Wild Boar Feast.

In 1971 we cleaned out our firm bank account and took off by car to the May Day action in Washington, D.C., where we started out as participants in the action to “shut down D.C.” in protest against the Vietnam war and wound up lawyering to get our comrades out of jail. Later that summer we went to the riotous National Lawyers Guild convention in Boulder, Colorado, where it was decided amid great controversy that legal workers, jail house lawyers, and law students could be members of the previously all-lawyer Guild, the progressive bar association through the decades representing the Movement.

One thing we always did on these trips: have a big old good time. Cam was the leader of this fun, with all of us singing at the top of our lungs, quaffing any available spirits, toking and talking the talk, later recalling the great stories repeatedly even when they made us look bad — especially when they made us look bad! We were doing exactly what we wanted to do in a time when it counted for more than any other time.

If Cam was the leader of merriment, Brady was the provider of mellow entertainment with his guitar and voice. I tried to crack jokes, often so droll Cam did not recognize the joke and took it literally, as a Midwesterner is wont to do. (He often spoke of growing up in Detroit.) This was the beginning I guess of small rifts between us.

One night sitting at the old Villa Capri Motel dining room in Austin, Cam excoriated both Brady and me for the conventional, sell-out law we had been guilty of prior to coming under his tutelage. It got so bad we all three slammed out of there in different directions. At a time when there was definitely a bit of tension, we were saved again by adding legal ballast to the firm. We were lucky enough to gain two great new partners, Bobby Nelson and John Howard in fall 1972 at the old 15th Street law office. And soon we were back to doing what we set out to do, representing the Movement.

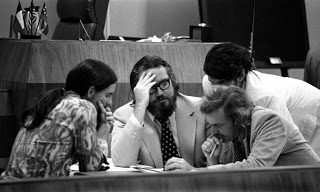

In 1972 Cam and Brady were part of the legal team that represented the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) in a trial in Gainesville, Florida. The Gainseville 8 were charged with conspiring to blow up the Republican convention. In 1974 John Howard and I represented a defendant in the Wounded Knee occupation (as we might call it now). There had been a siege of 71 days to a standoff with blazing guns. The Indians and their allies who held the store against the FBI were charged with multiple felonies in federal court.

I am unsure of the year, but in that same period, Bobby Nelson was part of a delegation to Cuba. We all had our Movement cases in and around Austin involving defense of GI’s, SDS members, civil rights activists, lawsuits concerning women’s rights, gay rights, and the counterculture in myriad legal battles. The law firm was an institution in the community of Movement groups and people from that Montreat beginning — Cam’s vision and determination — to the end of the firm in 1977, the year Cam moved to the Bay Area of California.

[Jim Simons practiced law in Austin for 40 years, representing many movement activists, including anti-war GIs. Jim served as a counsel for members of the American Indian Movement who were arrested at Wounded Knee in 1974. After he retired he published his memoir Molly Chronicles in 2007. Read more articles by Jim Simons on The Rag Blog.]

Cam and Jim were the lawyers for the Chuchwagon 21, which included me, Spencer, Meachum, Jay McGee and numerous others. Warren Burnett and Maury Maverick also signed on to our legal team and certainly helped intimidate the DA into eventually dropping or reducing all the charges. But Cam and Jim did all the groundwork. They got paid spare change from benefits. I shall be eternally grateful to them.

David P. Hamilton

Those guys…where do I start? They defended my criminal cases for free. They sued the Austin Police Department on my behalf. They gave me my first law job outside of the United Farm Workers. Basically taught me how to find the courthouse door and what to do then. Oh, and we had some great times along the way, as Jim said.

Cam was not only my attorney, but was a friend. All of this “law firm” were great people and defended us whenever needed, and VVAW people in Austin often needed defending in court. They got me out of jail and charges dropped over a speach outside Oleo Strut, helped get me out of jail in Florida as a member of the Gainesville 8 (12) and Cam helped me “escape” to New Mexico with my then 3yr old son. Thankfully I was not one of the Wounded Knee defendants, they didn’t catch me. May the gods be happy with you Cam, and smile on the rest of you, well deserved.

Thank you,

Wayne Beverly

Thanks for your support of everyone you mention here, especially your support of the VVAW. They, of all people, knew what they were protesting, and your services helped them to get the word out.

Betty DuBose Hamilton

Cam and Brady got several of us out of jail when we (dressed as witches) hexed the LBJ Library before its gala opening: “the blood of the Vietnamese people will haunt you forever.” The granite facing fell off the building shortly thereafter. And Jim, thanks for springing me from a D.C. jail during the MayDay protests. Unending thanks and solidarity, Alice

My fondest memories are of “Freight Train” Cunningham, the only truly “feared” batter in the annual softball game between the hippies and their lawyers aka, The Zapatistas vs. the Bold Marauders in Pease Park. OMG that guy could hit the ball a mile.

Little did we know at the name of our event, The Conference on Creative Disorder would one day become the modus operandi of the Republican Party (well maybe not the “creative” part). Nor did we suspect our tongue in cheek motto of the tourney, “Fuck you! Hooray for me!” would become the RP’s bona fide mantra. Probably would have rethought the whole thing had we known.

Dear Cam- Cool Runnings! Peace be the journey.

Zapata Lives!

I was living in the old Hunnicutt House up on the hill by the Capitol and above the court house. I do not remember the immediate cause, but there was an emergency at the court house. Cameron was attending some event but responded to a call, showing up quickly, still attired in full regelia with his grand Scotish kilt.

Everyone was quite impressed.

May the bagpipes resound !