It’s not just the whites reaching for the black culture, it’s the blacks reaching for the white culture. It’s about the collision.

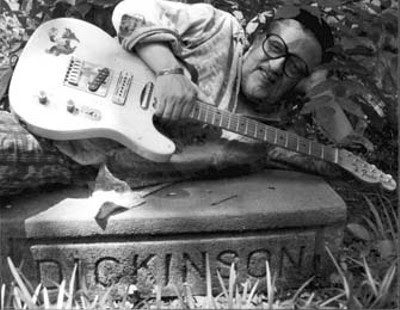

Memphis musician Jim Dickinson dies at 67

Career of artist, producer touched four decades, many livesThe North Mississippi Allstars have lost their father, Bob Dylan has lost a “brother,” rock and roll has lost one of its great cult heroes and Memphis has lost a musical icon with the death of Jim Dickinson.

The 67-year-old Dickinson passed away early Saturday morning in his sleep. The Memphis native and longtime Mississippi resident had been in failing health for the past few months and was recuperating from heart surgery at Methodist Extended Care Hospital…

— Bob Mehr / Memphis Commercial Appeal / August 15, 2009

An oral history:

By Joe Nick Patoski / The Rag Blog / August 27, 2009

There are cool cats and there are cool Memphis cats but no one, not Elvis, not Jerry Lee, not even the Wolf came close to epitomizing Memphis and cool like Jim Dickinson did. He was the Top Cat Daddy, an inspiration, a mentor and my friend.

If you knew his music and understood his role as one of the links between black and white culture and between blues and rock and roll, you know what I’m talking about. If he is unfamiliar to you, now’s as good time as any to get to know him, even though he’s checked out of the motel.

Read Jim Dickinson’s obitiuary in the Memphis Commercial-Appeal’s obituary.

In honor of his spirit, I share the oral history he did for me back when I was working on the Voices of Civil Rights project in 2004. His physical body may be gone, but his words and his music live on.

To passersby on the two-lane blacktop winding through the Hill Country of northern Mississippi just south of Memphis, the eclectic collection on the other side of the gate consisting of two mobile homes, a ramshackle barn, a small one-room frame house known as the Fortress of Solitude, an abandoned yellow school bus, and an ancient pre-Airstream trailer may appear to be nothing more than a duct-taped testament to Southern poverty. But as far as Jim Dickinson is concerned, he lives in the lap of luxury.

The barn houses a recording studio where Dickinson, a noted Memphis musician and record producer, works. The TV is wired to cable so he can watch old black-and-white westerns and his beloved wrestling. His hound dog Lightnin’ rests at his feet contentedly while his wife, Mary Lindsay, goes on and on bragging about their sons, Luther and Cody, and their band, the Northern Mississippi All-Stars — Luther’s Jaguar is parked in front of their mobile home while they’re on tour. The family photograph hanging among the Zebra skins and various and sundry memorabilia cluttering the walls was taken by Annie Leibowitz.

“Jim, you have everything a man could want,” Bob Dylan told him when he visited the spread known as Zebra Ranch a few years back. “A man could do a lot of thinking here.”

Jim Dickinson makes a passionate, articulate case for Memphis being the greatest music city in modern history. As the home of Elvis Presley, it was for all practical purposes the birthplace of rock n’ roll. It is also the rich melting pot where blues, rhythm ‘n’ blues, and soul, hillbilly, rockabilly, and country & western mixed and blended to create the most American of sounds. To achieve this feat, Memphis musicians like Dickinson, both black and white, defied Jim Crow laws and crossed color lines out of the simple desire to make music. By doing so, they broke down barriers long before the courts or lawmakers got around to changing laws.

I was born in Little Rock, lived in Hollywood as a tiny infant for six months, moved to Chicago where I lived until I was almost 9. In 1949, we moved to Memphis, where I was actually conceived. The fifties were about to happen. The world changed in front of my eyes.

My father worked for Diamond Match Company. He’d been an executive vice-president until they closed the Chicago office. Rather than move to New York like the rest of the company did, he’d saved himself with a demotion job in the South, so he could be near his family in Little Rock. Memphis was as close as he could get.

I thought we’d moved to Hell. I was a city boy. I’d spent times at my grandparents in Little Rock in the summer, so I’d been exposed to the South. We moved into what wasn’t yet suburban East Memphis: there were cotton fields in front of my house and a truck farm behind it. I was coming from the National College of Education in Evanston where in the first grade I had six teachers and we changed classes. I had an arts & crafts teacher who had a navel jewel on her forehead. I came to Memphis to a school in Shelby County where they let out classes for cotton picking. I seriously thought it was a school for farmers. “Well, farmers gotta go to school somewhere. This must be it.”

I really thought it’d been a terrible mistake. Gradually, I came to love it and can live only here now.

Cultural differences? My father bought this three-acre piece of property in east Memphis with a big ol’ house on it. It’d been vacant for some time due to a divorce case. He had hired this black guy from the local crossroads called Orr’s Corner where the blacks hung out to clean the place up when he bought it. My mother and I were still in Chicago.

We drove in the driveway for the first time, the first thing I saw was Alec. His name was Timothy Teel, but they called him Alec because he was a smart alec. He was real short. He was the first thing I saw in my new home. He became my teacher.

He took it upon himself as part of his job to teach me the things I needed to know, and not be a smart alec Yankee kid, which I was. Alec taught me about nature and life.

He taught me how to throw a knife underhanded. How to shoot craps, play pittypat and smut. He was a great singer but he didn’t play an instrument, and when he realized I wanted to play music, he brought me musicians to teach me. It was very Uncle Remus, very politically incorrect, and probably the most valuable relationship of my life outside my family.

Alec must have been in his late twenties. He was very much the young buck. They called him The Ram in the neighborhood. He stabbed a couple guys. My father had to get him out of jail periodically. He was an inspirational role model.

He was the yard man. He’d put on his white jacket and do dinner parties for my mother. His mother was a part-time maid. His wife was my baby-sitter. It was like a family deal.

My father became very much the white man of the neighborhood. We referred to the colored section as being Down The Road. It was like another world, and totally inaccessible. Old man Orr, who owned the grocery at Orr’s Corner, would lend blacks money at real high interest rates, a real plantation mentality. My father developed into the anti-Mr. Orr. He was very much the Captain and was treated as such. I grew up with a very definite double standard in that way.

The single, most important motivating thing that happened to me in that same period of time was seeing the Memphis Jug Band — Will Shade, Charlie Burse, Good Kid [considered the most important jug band of all time, with roots dating back to the 1920s.] It took me years to find out who they were, but I saw them downtown with my father one Saturday afternoon. After hearing that music, other things in life didn’t seem to be as important as that did. I spent the next 10, 15 years of my life, trying to find that music.

It was right down the road, literally, but I couldn’t get there in 1950. A white kid couldn’t go where the music was.

I’d never heard anything like it. You have to imagine what music was like in 1950. I was already interested in music and had taken music lessons. My mother was a piano player, played in the Baptist Church. I was classically trained, but I had real screwed up vision. I couldn’t see multiple images and I still can’t read music to this day. So at this point, in my mother’s eyes, I was already a failure as a musician.

I heard some Dixieland and some boogie-woogie on the radio that had interested me. There was a piano player in Chicago called Two-Ton Baker the Music Maker, who had a radio show. I heard him playing boogie-woogie and that kind of interested me. There was no rock and roll on earth.

But when I heard Will Shade and the Memphis Jug Band, it was like hearing Martians play music. It was so transcultural. He was singing, “Come on down to my house, Honey. There’s nobody home but me” and playing this string tub bass, which was this string coming out of this metal washtub tied on to a broom stick while Good Kid played a washboard with drumsticks. This was not typical music that a nine year old white kid would encounter.

It utterly changed my life.

Jim, me, and my sister, Christina Patoski, looking at him was

Several years later, Alec brought me a piano player to teach me. He’d work half a day on Saturday and come in hungover, wash my father’s car, and get paid. On Saturdays is when he’d bring me musicians. He brought me this guy who was legendary. I don’t know what his real name was. They called him Dishrag. You hear people talking about Memphis music history, talking about Dishrag. He was a notorious alcoholic and was dead drunk the day I saw him. Obviously, they’d both been up all night. Never took his overcoat or his hat off, sat down at my mother’s piano, and started to play like nothing I’d ever heard.

I asked him if he knew, “Come On Down to My House, Honey, There’s Nobody Home But Me,” the song I’d heard Will Shade sing, which believe me, I’d never heard again. He grinned and kind of chuckled and said, “How do you know that song? That song’s older than you are.”

It opened him up and Dishrag showed me the thing that enabled me to learn to play the piano, the thing my mother and my other piano teacher had been incapable of doing.

He said — again, this is as politically incorrect as it could possibly be, and I have to go into ebonics — he said, “Everything in music is made up out of codes.” I thought he meant codes like secret codes, Captain Marvel, Morse code. Of course, he meant chords. But I thought he said it was all made up out of codes and I thought, “No wonder I can’t damn well do it. My mother didn’t tell me it was code. This guy’s about to give me the secret here.”

And he did.

He said, “You takes a note, any note” — his index finger went to an E note on the piano. “You goes three up” — and his hand went up three keys — “And you goes four down” — and his next finger went four down. These are not musical half-steps. These are just keys on the piano. He ended up with one finger on C, one finger on E, and one finger on G — which is a major C triad. And it works anywhere on the piano — he said, “You goes three up and four down, just like poker.” That’s the part I never understood because that’s not the way I was taught to play poker. Obviously, it was for Dishrag. You go three up and four down and it makes a code. At that point, I realized he was talking about a chord, nonetheless, he gave me the information that I needed. Because it does work anywhere on the piano, it does make a major triad, and your thumb is always on the tonic root note.

With that piece of information, with a chord in my right hand, and an octave in my left hand, that’s all you need to play rock and roll. To this day, that’s basically what I do. I play an octave and a major triad. If you play it back and forth between your hands, right, left, right, left, then you have a shuffle. If you play it straight, you’ve got eighth-note rock and roll.

That’s the racial difference.

The racial difference of music is how the implied eighth-notes of rock and roll are handled. Whether it’s politically incorrect or not, I don’t care. It’s absolutely true. Black people do it one way. White people do it another way. The difference is feeling, therefore, interior. Not to be too anthropologic.

My parents thought it was a good thing. My mother and Alec had a very special relationship. As a Christian lady, she took it upon herself to reform Alec, to give him the information and education that he had lacked in his life.

She had a picture of Shakespeare and a little miniature of Romeo and Juliet on the wall of the room my grandmother stayed in. Alec was in the room with my mother one day, looking at the picture of Shakespeare. “Who that be?” he asked. “Abraham Lincoln?”

Imagine my mother explained to Alec, who dropped out of school in the fourth grade, who Shakespeare was. This is the kind of thing I witnessed as a child.

Alec, when he came to work for us, didn’t believe the world was round. As he was dusting one day, he saw a globe and asked my mother what it was. When she explained it to him, he didn’t believe it. Finally she convinced him that the world was round like a ball. When I talked to him later, he explained he thought it was a ball, but that we were inside. Which does make a lot of sense.

He gave me many an important life’s lesson.

Years later, I recorded him in my carport for a project I did for Beale Street redevelopment. He couldn’t sing inside, and he had to work in order to sing, so he chopped wood while he sang and I recorded him. People hear the recording say it sounds like a chain gang, which is entirely different from what it really is. It’s one of the best recordings I ever made.

[As a young man, Dickinson’s quest forced him to cross barriers erected by segregation.]

The lines were very real and could not be crossed. Music created the problem. My parents certainly saw it as the problem. The racial situations that developed in my family were all a result of me seeking after the music.

After I’d been to college and supposedly knew better, I signed my first record deal with Ruben Cherry’s Home of the Blues label. Ruben Cherry had a record store on Beale Street. ‘Course, he was a white Jewish guy. Everybody on the label but me was black. I had this lame Jimmy Reed thing I was doing. He would play my tape for a roomful of people and have them guess who was singing. They’d guess everybody who was black before me. He called me Little Muddy. He used to take me to these various black functions where we’d be the only white people.

One of which was an Ike and Tina Turner Show where I ended up in this photograph I would give anything to have now, of me standing between Ike and Tina Turner. It was taken by Ernest Withers, the famous Beale Street photographer who is now a famous art photographer. Back then, he was a black society photographer.

I came home, drunk. The picture fell out of my sport coat pocket when my mother hung it up the next morning. There was hell to pay. My father said, “Don’t you realize this would ruin my business?” And it would’ve, then. My parents, who were good Christian people and did not think of themselves as racists, were. Our politics were never the same. The older I got, the worse it got. But the music was always the thorn of the problem.

The only time I heard my parents speak the N-word was in regards to the music, not any human being or person: “Don’t go playing it.” Listening to it was bad enough.

“Why do you have to play that loud N—– music?”

I tell you why. Because it was in my head and it was driving me crazy.

One of the most important things Alec showed me was WDIA, the black spot on the dial [the Memphis radio station at 1070 on the AM band that was the first radio station in America to be programmed by African-Americans for African-Americans]. This was not common knowledge in the white community in 1950. It’d just been on the air three years. When Alec came in to eat his lunch, he’d change the radio to this wonderful thing. It didn’t take me long to figure it out. Everything was segregated, even the damned radio.

That’s what Dewey Phillips did in Memphis that was so revolutionary. There can be no discussion about race relations in Memphis without talking about Dewey Phillips. He’s the disc jockey credited with playing Elvis Presley on the radio for the very first time. Which would have been enough, if that was all he ever did. But what Dewey did was, he created the mindset in Memphis, Tennessee that was Elvis Presley.

Elvis Presley heard “That’s All Right, Mama” on Dewey Phillips’ “Red, Hot & Blue” radio show on WHBQ because Dewey Phillips was the only white man who played black music. There were four radio stations that played white music for white people and two black stations that played black music for black people. Dewey Phillips would come on the air and he’d play his theme music and say, “Ho, ho, good people” because that’s who Dewey was talking to — good people. He played good music for good people. He’d play Hank Williams and then he’d play Sister Rosetta Tharpe. This created a mindset in Memphis that’s still there.

Until recently, we had a white county mayor and a black city mayor. Both of these mayors are roughly my age or younger. And at one six month period of time, they both quoted Dewey Phillips in the newspaper, and I don’t think either one of them was aware of the fact they were quoting Dewey Phillips. Because Dewey Phillips was so powerful a force on the radio in Memphis, that everyone in the city was affected by him. Certainly every child, everybody listened to this crazy, pilled-up redneck playing this insane music.

It wasn’t until I went to college in Texas that I realized everybody wasn’t hearing it. I realized I had this arcane information that they didn’t have, simply from listening to Dewey Phillips on the radio. The racial idea that he got across, was the idea of Elvis.

Think about the five records Elvis Presley recorded on Sun Records, 45 rpm records, two songs, one on each side. On one side of each record was a jump blues song, or “black music.” On the other side was a country ballad, “white” music. This is what was happening in Memphis at the time. The urban blacks coming to town and the urban whites coming to town — rednecks, if you will — were culturally colliding. And what was coming out, was Elvis Presley.

He was not unique. He represented a lifestyle that already existed in Memphis. It was almost a racial imperative for some of these white redneck guys to play this weird black music. I know these men. And some of them are still not comfortable with it, racially, but they were compelled to do it.

It’s freedom. It does the same thing to me that it does to everybody all over the world. It symbolizes individual freedom of expression and freedom. That’s what it is.

To find it, it’s like my first music lessons when I couldn’t see the music. I would have never understood music in the European tradition. I still don’t. But when I heard Afro-American music, something happened. And it wasn’t just me. It was a whole generation of crazy white boys that this happened to. That’s what rock and roll is. Us trying to be them.

Alec brought me a guy named Butterfly Washington, fresh off the penal farm, still had a penal farm haircut. He didn’t teach me anything, he just played for me. His father owned a gambling joint down on Broad St where Alec used to go.

This is pathetic, but it’s true. For a middle-class white kid in the fifties, even though this music was literally right down the road, the only way I could think of to find it was in books. So I went to the library, and sure enough there weren’t any. There was a Nat Hentoff book called You Hear Me Talkin’ which had one chapter about blues and jug band music with specific references to the Memphis Jug Band. So I did find what I exactly needed. But that was all there was. There were no books about the blues because white culture didn’t care about the blues, and black culture was ashamed of it at this point.

When Sam Charters wrote the Book of Country Blues in 1959 it was the first book on the blues. Although it’s filled with misinformation, it’s still probably the best book on the rural blues. I assumed incorrectly this music was antique. I should have known from seeing Howlin’ Wolf on the radio broadcasting from West Memphis, Arkansas. I didn’t know who he was, but heard the music, followed the music, saw the strange black man playing, till my father came and got me, just like with the jug band.

I knew the music was there, somewhere out in the bushes, but I couldn’t get to it. Through books, I thought I could. When Charters came through Memphis, being a Yankee and relatively insensitive, he cut quite a wide path. I just followed his path. By following his path I found Gus Cannon, who was first for me. He was right there, cutting somebody’s yard. Gus told me where Furry [Lewis] was. Hell, I thought Furry Lewis was dead. He was sweeping Beale Street twice a day with a garbage can on wheels and a push broom. He did it for 36 years. When he retired, the city found out he had only had one leg, which made him disabled therefore unemployable, so he didn’t get any of his benefits. And that’s why they call it the blues.

Furry literally swept Beale Street and he was prouder of that than making records, and proudly so. I used to work with Furry and Bukka White. Right before he died I taught him to play “Sunshine of Your Love.” He thought it was so funny. He could only play part of the riff, then he’d crack up.

Through Ruben Cherry’s Home of the Blues record label, the music became accessible. It did become an obsession to seek out this music and try to emulate it. Rufus Thomas and I used to be on panels together and would always start arguments whether or not white people could play the blues. Towards the end of his life, we did this interview for some TV show, I realized we had both changed our minds. He used to always jump in there, “Aw, white people can’t play the blues.” This time, he said, “I’ve just changed my mind. I’ve decided that white people can play the blues — they can’t sing it but they can play it.”

I told him that I had changed my mind. That after 40 years of trying to play the blues, I’d decided that white people can’t play the blues. The same thing that had changed Rufus’ mind was the same thing that changed my mind, which was Stevie Ray Vaughan, who as far as I’m concerned, was playing rock and roll. Like me, he was trying, but something was coming out. It’s the same with the Beastie Boys or Justin Timberlake. They can play them but they can’t feel the syncopated nuance of the implied eighth-note shuffle. It is a thing that is black. And I’m sorry, but it is.

Before the Beatles, this was not all right. It was not cool to be a musician. This was socially questionable to be doing what I was doing. It was not all right to play black music, believe me. The Rolling Stones made it OK. When I was doing it in 1958 in East Memphis, it was not all right.

William Brown, who was one of the black engineers at Stax and one of the singers in the Mad Lads, a brilliant singer who’s sung background on a lot of my records, told this story to someone who asked how long he’d known me. He’d said, “I’ve known him since we was both too young to be where we were.”

He sang with his uncles then. He was the youngest person in the group. (I never told anyone why I had to play before. Interesting) There’s no liquor by the drink, a lot of the entertainment was private parties. This was a high school fraternity party at this dump behind a motorcycle shop on Summer Avenue at this place called the Theatrical Arts Club, which had nothing to do with theater or art, believe me. They did have a stage and had a PA.

My band played a lot of parties there. It was illegal to play racially mixed. This was an all white band that night playing behind black singers, which was illegal. William says that before the gig started, I started an argument with the guy from the fraternity because he was paying the band $15 a piece and he was paying the singers $12 a piece because they were black. I told him that my band wasn’t going to perform with $12 singers. Either he was going to pay the singers $15 or my band wasn’t going to play.

William never forgot it.

I didn’t see any reason to pay them less than me. Certainly I wasn’t as good as they were. He should’ve been paying me less than them.

There’s a certain thing which you can only learn playing with black musicians. There’s a look that a black musician can give you, when you’ve done something stupid, that causes you to never do that again. There’s no other way to learn that. You don’t have to experience that putdown more than two or three times to change your stupid white way.

I first started playing mixed when I started playing Mar-Keys jobs. The real Mar-Keys had kind of broken up and Ray Brown would take one Mar-Key and five other people and take them to Sikeston, Missouri, to play for a sock hop. I did a lot of that stuff. Some of the most fun I’ve had in my life.

There were hassles, even up into the sixties. I remember one night, coming home from a Mar-Key gig, a mixed band in the car, and the cops, I guess, picked us up at Dyer’s Drive In, the only place with a black side and a white side that stayed open late, one of the only places to get something to eat after a gig. We left some white guy off, they didn’t hassle us. We left the Shann brothers somewhere downtown in one of the ghettos. They were the last two black guys in the car. When they got out, the cops drove up and rolled down the window, this big ol’ redneck cop stuck his head out and says, “You might as well just go on and live with them.”

That was the way it was. I was glad they drove away.

I was more afraid of cops than any of the black joints I ever went in. (NEVER SAID THIS BEFORE) The biggest hassle I had in the fifties and early sixties going into black joints was from gays. Being hit on by black homosexuals, assuming because I was white in a black joint, I must have been gay.

I think the Civil Rights movement was a little different in Memphis than it was in other places. I sang “We Shall Overcome” a couple times at folk music shows and tried to be as politically incendiary as I could be, but I didn’t march or sit-in.

I was on a picnic with my then girlfriend and her family the weekend Ole Miss was integrated and we saw the helicopters go overhead. We were just south of Memphis. When I got back home, the phone had been ringing off the wall from friends who were going down to Oxford to participate in the disturbance.

You sort of didn’t talk about it, not till the mid sixties. By then, I was already so entrenched in what I was doing, I was obviously a social misfit and outcast amongst my people. It wasn’t an issue for me. I didn’t see a choice. I saw how emotional my parents became when they watched Little Rock Central, which they both attended, integrated on television. It was difficult to deal with. I still remember my mother’s preacher, who was an Ole Miss graduate, his sermon during the Ole Miss integration. It was hard for them good Christian folks to deal with. But it couldn’t change how I felt about the music and what I saw as a more honest way of life.

Things changed in 1968, but again, I think things changed less in Memphis. If King had been assassinated anywhere but Memphis, it’d still be on fire. But because of Dewey Phillips and the mindset that was at work here, when King was assassinated, Detroit caught fire, Atlanta caught fire, DC caught fire, LA caught fire. But Memphis didn’t burn. Because it’s different.

I think it’s because of Dewey Phillips. I think it’s that simple. It’s because of the music.

The body politic was the anchor, they were pulling it the other direction. Mr. Crump don’t like it! That’s what the song says, “Mr. Crump don’t like it/They ain’t gonna have it here.”

Mr. Crump is just dead, he’s not gone. Believe me, he’s down there right now and he still don’t like it. What it is that he don’t like is what we’re talking about. But, like the rest of the song says, “We don’t care what Mr. Crump don’t allow/We’re gonna barrelhouse anyhow.” That’s the way Memphis is.

I honestly believe there’s no place like Memphis, not racially. Today, every issue in Memphis comes down to race. The black culture is strong enough to survive, like Faulkner said. You have to look no further than rap music as proof that at this late date black culture is strong enough to do something that would be both repulsive to white people and compelling to their children. Is that not a miracle?

One of the reasons I live in Mississippi and you look around you here and see what has been depicted in the press, in both fact and fiction, as rural poverty. I don’t see it as poverty. It don’t look poor to me. It don’t look poor compared to Watts. These people will be here after the bomb drops. It’ll be cockroaches and the people in these sharecropper cabins. And their life isn’t even going to change much.

Now that’s not true of all of Mississippi. The Delta is mean, but it’s always been mean. It’s mean-spirited. It’s not just the white people that are mean. Black people are mean too. The Hill Country is not that way. The Hill Country is not like the Delta because it wasn’t desirable for plantation ownership. Some of these farms go back three, four generations — the black farms. There’s musical families who’ve been here long enough to create a tradition. This was not true in the Delta because all the people were itinerant, if they weren’t sharecroppers. They weren’t tied to the land. The musicians weren’t tied to the land. They all moved around. So there was no feeling of community like there is here. I love it here.

At least not have to answer to the man.

Again, it’s the fear of the cops. It’s the fear of authority.

The Hill Country hanging on to the blues tradition is some kind of miracle.

Somehow, Robert Palmer, the writer, was right. When he moved to Holly Springs, I thought he was crazy. But he was dead right. The Fat Possum label, although I disagree with them and their marketing technique of presenting the blues artist as primitive savage, a man I think of as literally a holy figure, what they’ve done is a miracle. First time I heard R.L. Burnside was 30 some odd years ago. Friend of mine made a tape of him. The first word out of his mouth was the N-word. I thought to myself, “God, this is so good, no one will ever hear it.” Well, now, R.L. Burnside has had a career. He opened for the Beastie Boys, the Cramps — that’s a miracle. And that’s progress. You can’t tell me it’s not racial progress.

Couple years ago at the Sunflower Blues Festival which is the only Mississippi blues festival left that hasn’t turned into a Bobby Rush concert — not to say there’s anything wrong with Bobby Rush, he just doesn’t have much to do with the Mississippi blues — I had been invited to be on some panel. My wife and I went down to Moon Lake, have a romantic night before the event. We went down into Clarksdale for breakfast in the morning. This was on the square, traditional little Mississippi restaurant. At the back table were these six big fat guzzled-gutted redneck businessmen who obviously were there every morning.

Without really listening, we could hear these men talking. Within the 45 minutes it took us to eat our breakfast, these guys who I venture to say 10-15 years earlier would have been in the Klan, may have still been — one guy obviously owned the restaurant — discussed Robert Johnson and William Faulkner. These are names that would have not been spat from these men’s mouths 10-15 years ago. They were discussing them both, in terms of tourism, admittedly. But they were still discussing Robert Johnson and William Faulkner as positive elements in their community.

As we left, they were standing up to leave about the same time we were, the big fat one who obviously owned the restaurant said, “You know, sometimes I have a hard time with them damn Faulkner stories. I don’t understand them.” This other guy, quick as a heartbeat, said, “Yeah, well, sometimes you’ve got to read them two or three times.”

Maybe there hasn’t been much progress, but anyone who says things haven’t changed in Mississippi doesn’t know how bad it used to be.

It was so bad, it created music and art that are second to none anywhere on earth.

The Delta blues itself was maybe 30 men for eight years. And it won’t go away. Robert Johnson is on the pop charts. The Delta blues continues to be reissued, reexamined, recategorized, redocumented. How many millions of dollars did Martin Scorsese spend on putting on that extravaganza of the blues? Do you think Charley Patton thought about that? I don’t. How surprised would Robert Johnson be, that he had generated $5 million in income? I think he’d be pretty surprised. But I think he would equally surprised his picture was on the front page of the Commercial-Appeal newspaper. Things have changed.

My point is, pop music is created as a disposable item. It makes you want more, like ice cream. You’re not even supposed to keep it. The blues is ultimately collectable, there’s a beginning and end. You can put the blues in a box in a corner and stack it up. There’s something appealing about that to western man. The blues is not going to go away. The Delta blues, unlike commercial music, is art. And art endures.

There’s nothing like the literary tradition here in Mississippi anywhere in America. How can you explain blues and writers? It’s not just William Faulkner, it’s Larry Brown. It’s going on as we speak. It’s because of something in the area. I think it’s the spirit. I don’t mean to get too metaphysical on you here, but people think it’s literally in the air and the water and all that. Although that has a little to do with it — I think it has a lot to do with the altitude we’re at — but I think there’s a spirit. I think it comes and goes. You can always feel a little of it.

As bad as Beale Street is now — it’s turned into a tourist trap; anyone would admit that. I got in trouble describing it in the press as a city-owned liquor mall, but that’s what it is. The racial implications of what they did with Beale Street is truly ugly — if you walk down the middle of Beale Street, especially when there’s nobody there, you can still feel something. It ain’t like what W.C. Handy felt. And it’s not the Beale Street of Will Shade. But there’s still something there and what you feel is that spirit.

Obviously it likes it here, or it wouldn’t keep coming back.

Memphis is the capital of Arkansas and Mississippi. It’s certainly unlike everything east of the Tennessee River. The Delta literally begins in the lobby of the Peabody Hotel in Memphis. You come down off Rabbit Ridge and there it is — the Delta. Flat. There’s nothing like it in America. I can’t leave. I tried to leave once and I had to come back. If I stay away from Memphis too long, I start to play really funny.

It’s not just the whites reaching for the black culture, it’s the blacks reaching for the white culture. It’s about the collision. If you drove through the ghetto in the sixties, you heard Eric Clapton on the radio, you didn’t hear Ray Charles. That’s what Stax [Records] was. Stax represents the period of time where the races really met, culturally, and then, interestingly enough, went beyond each other. Which is what is happening now. What happened was special and unique. It will never go away. Isn’t that the prediction of Faulkner, of Jim Bond, that it would all turn gray? Isn’t that what should happen.

Justin Timberlake [of the teen singing group N’Sych] was exposed to the result of Dewey Phillips. He was certainly exposed to Al Green. He’s doing the same thing Elvis did. He’s using a black idea, he’s singing in falsetto. What’s getting him across is the way he dances. He’s tremendously professional. He’s crossing racial boundaries. I think it’s a good thing. I don’t buy into any of this exploitation crap, the white musicians exploiting the black culture. That could not be farther than what I buy into. What it’s all about is the white musicians reaching for the black culture and the black musicians reaching for the white culture. If we all stay in our own backyard, what fun is that?

What was Nat King Cole if he wasn’t trying to sound white? There isn’t anything wrong with that. He was the first black man in Bel-Air. That was an accomplishment. He wouldn’t have got there if he was singing like Howlin’ Wolf. Here Johnny Ace from Memphis trying to sing like Perry Como back in the fifties. He wanted to get across. Should’ve kept that gun out of his mouth. That’s another issue.

I was conceived in Memphis and my mother thought is was somehow pagan to be born in Memphis so I was born in Little Rock. I think I somehow belong here. I must have been supposed to see what I saw, because I saw it.

If nothing else, a lot of black pseudo-intellectuals can listen to this and be horrified.

[Joe Nick Patoski, who lives near the village of Wimberley in the Texas Hill Country, writes about Texas and Texans. He has authored biographies of Willie Nelson, Selena and Stevie Ray Vaughan and has been published in numerous periodicals including Rolling Stone and Texas Monthly. This article was also posted to his blog, Notes and Musings.]

Very nice piece on Jim. I linked my blog on Jim to yours.

http://drewciferstonezone.com

This is an extraordinary tour of Memphis and the Mississippi Delta from the back seat of a car filled with black and white musicians coming home from a gig. Jim Dickinson's insight and thinking about race in the land of Robert Johnson and William Faulker are often unconventional and surprising, always delightful, and Joe Nick has captured the roots patois. This needs to be anthologized.