Mexico’s Gaza:

The long night of San Juan Copala

Much as the Israeli government had warned the organizers of the Freedom Flotilla not to set sail for Gaza, the Governor of Oaxaca advised the activists to turn back or face the consequences. Like their international counterparts on the aid ships, they refused.

By John Ross / The Rag Blog / June 18, 2010

MEXICO CITY — The volunteers set out in high spirits on their mission to deliver tons of humanitarian aid to a besieged community that had been denied basic necessities for many months. But within sight of their destination, the convoy came under heavy fire from paramilitary gunmen and in the pandemonium that ensued, a much-respected human rights activist and an international observer were killed and a dozen wounded, including several reporters who had accompanied the caravan.

Sound familiar?

But this mission was not headed towards Gaza and the assassins were not Israelis. Rather, the volunteers’ goal was to reach the autonomous municipality of San Juan Copala in the remote Triqui Indian zone in the northeastern corner of Oaxaca. 700 Triqui families, about 5,000 villagers, have been denied food deliveries, electricity, and medical and educational services for the past nine months. Phone lines have been cut by the paramilitaries who command the road to Copala.

Much as the Israeli government had warned the organizers of the Freedom Flotilla not to set sail for Gaza, the Governor of Oaxaca advised the activists to turn back or face the consequences. Like their international counterparts on the aid ships, they refused.

When the activists turned off the main highway at La Sabana, a hamlet within miles of their destination this past April 27th, gunmen under the orders of a local cacique (rural boss) Rufino Juarez, the “director” of a paramilitary group dubbed the UBISORT (“United For Social Welfare In the Triqui Region”), and affiliated with outgoing governor Ulises Ruiz, turned their weapons on the caravan.

Many of the volunteers abandoned their vehicles and fled for their lives, taking refuge behind nearby rocks. But Bety Carino, an indigenous activist and defender of native corn and one of the convoy’s organizers, fell under a hail of bullets. Finnish solidarity worker Jyri Jaakkola immediately threw himself across Bety’s bleeding body, cradling her head in his hands but he too was cut down by the paramilitary fire.

The 33 year-old Jaakkola was the second international activist to be slain under the murderous regime of Governor Ruiz. On October 27, 2006, independent journalist and social justice advocate Brad Will was fatally shot by Ruiz’s police at a barricade just outside the state capitol. At least 25 Mexicans were killed by Oaxaca security agents during the seven month-long 2006 uprising that was ignited by a police attack on striking teachers.

Inspired by the teachings of Ricardo Flores Magon, the Oaxaca-born anarchist and an ideologue of the 1910 Mexican revolution, Jyri Jaakkola traveled to Mexico in 2009 as a representative of a Finnish solidarity group to document human rights abuses in that conflictive southern state.

An anarchist himself, Jyri was much influenced by the writings of Murray Bookchin, the late Vermont-based social ecologist, and radical Brazilian educator Paulo Freire, whose counsel he took to heart when he sought to protect Bety Carino: “solidarity means to put oneself in the place of those that we act in solidarity with.”

International activists have journeyed to Mexico to align themselves with social change movements literally for centuries. The Spaniard Javier Mina fought against the Crown for Mexico’s Independence in 1821. The “San Patricios,” Irish-American volunteers, took up arms against the U.S. invasion of 1846 and were hung for their troubles. U.S. writers John Reed and John Kenneth Turner were significant voices in the landmark Mexican revolution.

The governments that inherited the mantle of the revolution were often thin-skinned and didn’t appreciate criticism by non-Mexicans. Article 33 of the 1917 Mexican Constitution gave presidents fiat to deport any “extranjero” (literally “stranger”) whose stay in country they considered to be “inconvenient.” The Italian-born U.S. photographer Tina Modotti was tossed out of Mexico in 1930 because of her affiliation with the Mexican Communist Party.

In a xenophobic rage during the most incandescent moments of the 1994 Zapatista rebellion in Chiapas, President Ernesto Zedillo ordered over 400 non-Mexican human rights observers deported, most of them North Americans, Italians, and Spaniards but at least a few Norwegians too. An entire class of students from Evergreen College in Washington State were 33’d after accompanying the beleaguered farmers of San Salvador Atenco in the May 1, 2003, International Labor Day march.

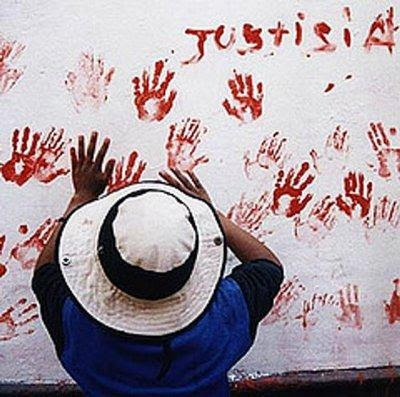

Much as internationalists Rachel Corrie and Tom Hurndall were slain by the Israeli Army in Gaza, Jyri Jaakkola and Brad Will left their lives in the blood-drenched soil of Oaxaca. Like the Israeli government, Ulises Ruiz washes his hands of all responsibility. “Who knows what these blue-eyed visitors wanted? Did they come as tourists or to make trouble for us?” he asked reporters after Jaakkola was murdered by his proxy gunsills.

State prosecutor Luz Candalaria Chinas is equally suspicious of the outsiders’ intentions, echoing the Israeli government when she described the international volunteers as “troublemakers masquerading as humanitarian aid volunteers.”

San Juan Copala, the April 27th caravan’s destination, has been wracked by spasms of homicidal violence for decades. The skein of killings stretches back to 1976 when popular community leader Luis Flores was assassinated by unknowns. In March 1984, Amnesty International sent a team into the Triqui region to probe 37 murders of indigenous activists. Most of the victims were affiliated with the Unified Movement of Triqui Struggle or MULT, founded in 1981 to defend 13,000 hectares of woodlands from the depredations of mestizo caciques from nearby Putla de Guerrero.

The next year, the AI team published a report “Human Rights Abuses In Rural Mexico: Oaxaca and Chiapas,” the London-based organization’s first investigation into pandemic violence in southern Mexico. The report documented “credible allegations” of extra-judicial killings, torture, police abuse, forced confessions, and the failure of authorities to investigate citizens’ complaints.

The AI document was instantly rejected by the Mexican government, then controlled by the Institutional Revolutionary Party or PRI. Under-Secretary of State Victor Flores Olea (now a columnist for the left daily La Jornada) questioned Amnesty International’s “objectivity.” Twenty five years later, the governments of President Felipe Calderon and the much-maligned Oaxaca governor Ulises Ruiz have perpetuated this tradition by rejecting every subsequent Amnesty International alert to human rights abuses in the state on similar grounds.

Armed with the Amnesty report, I visited San Juan Copala in the spring of 1987. Tensions were running high. Soldiers from the 28th Military Region, which had been linked to the slaughter of the MULT members, patrolled the dusty streets. I met with the Council of Elders and compared the lists of the dead — 13 more had been added since the Amnesty International report was formulated.

Later, I climbed a hillside overlooking the town and snapped photos. Abruptly, five soldiers burst out of the bushes and pointed their automatic weapons at my head. Then they confiscated my camera (I protested that I was only photographing some nearby chickens) and escorted me up to the highway with a warning never to return to San Juan Copala.

Today, nearly a quarter century after the initial Amnesty International report, the death toll in the Triqui region has mounted to over 400.

Ever-present tensions in the majority indigenous state of Oaxaca are exacerbated by upcoming July 4th elections to choose Ulises’s successor. According to a consensus of polls, the outgoing governor’s hand-picked “gallo” (rooster), Eviel Perez of the long-ruling PRI party, is running neck and neck with Gabino Cue, representing an unlikely coalition that includes both the left-center Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) and the right-wing PAN, Felipe Calderon’s party. The PAN is widely believed to have stolen the 2006 presidential elections from Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, the PRD’s candidate. Although the PRI ceded national power to the PAN in 2000, it has continued to rule Oaxaca with an iron hand.

Electoral tensions reverberate in San Juan Copala. During the stolen 2006 vote taking, some MULT leaders lined up behind the local Party of Popular Unity (PUP), a puppet of the PRI designed to siphon off votes in indigenous regions from Lopez Obrador and his slate. Soon after, the MULT split and on January 1, 2007, the MULT-Independiente or MULT-I peacefully took power in Copala, declaring the Triqui village an autonomous municipality modeled on Zapatista “autonomias” in Chiapas.

Under provisions of the never-ratified San Andres Accords on Indigenous Rights and Culture negotiated between the Zapatista Army of National Liberation and the Mexican government in 1996, majority Indian municipalities would be granted limited autonomy over land, habitat, exploitation of natural resources, the environment, education, health, and agrarian policies. Authorities would be designated by traditional Indian uses and customs and not by political parties. Self-declared autonomous communities in Chiapas, Guerrero, and Mexico state (San Salvador Atenco) have chronically been under the “mal gobierno’s” (“bad government’s”) gun.

Since the MULT-MULTI split and the uptick in the aggressions of Ulises’s UBISORT, escalating violence has torn San Juan Copala asunder. Marcos Albino, the human rights representative for the autonomous municipality, counts 25 fresh deaths in the last six months alone.

On May 26th, Timoteo Alejandro Ramirez and his wife Tleriberta, historic founders of the MULT who left the organization in 2006 to form the MULT-I, were murdered at their home in Yosoyuxi near the county seat of Copala. The motives for the double killing remain murky. Ramirez had been accused by political enemies of the disappearances of two Triqui sisters, 14 and 21, whose families are associated with the MULT.

Other victims include two community broadcasters, Felicitas Martinez and Teresa Bautista, slain in April 2009 on the road to Copala. Felicitas and Teresa, protégés of Bety Carino, had a popular call-in show on the local low-watt MULT-I station “The Voice That Breaks the Silence.”

Despite years of killing in Copala and a slew of Amnesty International human rights alerts, the federal government and the state of Oaxaca have declined to intervene to halt the violence. “It is between them. It is their silly uses and customs that is responsible for the killings. Only the Triquis themselves can fix this up,” Oaxaca prosecutor Chinas argues.

The shocking violence in the Triqui zone and the murders of Bety Carino and Jyri Jaakkola has had national and international resonance. In early June, the European parliament called upon Mexican president Felipe Calderon to open a through investigation into the deaths of the activists. A new caravan was mounted led by a PRD congressional delegation. Governor Ruiz immediately condemned the renewed effort to deliver humanitarian aid to San Juan Copala as outside interference in the upcoming gubernatorial elections.

On June 8th, 250 activists, many aligned with the Zapatistas‘ Other Campaign but led by 15 PRD federal deputies, left Mexico City in a seven bus convoy for the 500 kilometer trip to San Juan Copala, hauling 30 tons of food, clothing, and medical supplies. Both the Mexican military and the Oaxaca governor refused to provide protection — although AG Chinas promised the state would send agents to check the documents of international observers and warned the Caravanistas of the dangers they faced.

Once again, the activists refused to turn back and as in April, the convoy only got as far as La Sabana. The road to Copala was blocked by large boulders. A string of Triqui women under Rufino Juarez’s command and backed up by ski-masked paramilitaries with long guns refused to allow the buses to pass. Shots were heard further down the valley. State police who were keeping tabs on the buses bailed out right away. The bus carrying the PRD deputies turned around and headed back to Mexico City, followed reluctantly by the Other Campaign activists.

As in the struggle to break the blockade of Gaza, the solidarity workers are not throwing in the towel — a third all-women caravan is being planned.

The Israeli Navy’s May 31st massacre of nine Turkish pacifists carrying humanitarian supplies to Gaza has triggered a worldwide wave of indignation and Mexico City is no exception. When, during the first week in June, a score of Mexicans gathered outside the Israeli embassy in the affluent western suburbs of this monster megalopolis, half the protesters were Triqui women dressed in their traditional bright red embroidered huipiles that make them look sort of like plump strawberries. Behind the barricaded doors of their embassy, Israeli diplomats must have been baffled.

“What the Israeli government did to the activists bringing aid to Gaza is exactly what Ulisis and his paramilitaries did to us,” explained Marcos Espino, “we came here today to offer our solidarity with our brothers and sisters in Gaza. A lot of our people have been killed too.”

[John Ross’s El Monstruo – Dread & Redemption In Mexico City (“pulsating and gritty” – New York Post) is hunting for a Spanish language publisher. Those in the know can write him at johnross@igc.org.]

- See Dick J. Reavis’ review of John Ross’ El Monstruo on The Rag Blog.

Jefes, always the Jefes. Why did this happen?