The next Mexican Revolution:

Don’t look now but the long-awaited resurgence of the Mexican Revolution has already begun.

By John Ross / The Rag Blog / September 22, 2010

MEXICO CITY — As the 100th anniversary of the Mexican revolution steams into sight, U.S. and Mexican security agencies are closely monitoring this distant neighbor nation for red lights that could signal renewed rebellion.

The most treacherous stretch for those keeping tabs on subversion south of the border is between September 15th, the recently celebrated bicentennial commemorating the struggle for Mexico’s independence from Spain, and November 20th, the day back in 1910 that the liberal Francisco Madero called upon his compatriots to take the plazas of their cities and towns and rise up against the Diaz government.

At least 10 and as many as 44 armed groups are currently thought to be active in Mexico and the two months between the 200th anniversary of liberation from the colonial yoke and the 100th of the nation’s landmark revolution, the first uprising of landless farmers in the Americas and a precursor of the Russian revolution, is a dramatic platform from which to strike at the right-wing government of President Felipe Calderon.

Among the more prominent armed formations is the Popular Revolutionary Army (EPR) which rose against the government in 1996 and is based in Guerrero and Oaxaca, and three distinct split-offs: the Democratic Revolutionary Tendency (TDR); the Justice Commandos – June 28th, thought to be linear descendents of the followers of guerrilla chieftain Lucio Cabanas who fought the government along the Costa Grande of Guerrero in the 1970s; and the Revolutionary Army of the Insurgent Peoples (ERPI) which also espouses Cabanas’s heritage and is active in the Sierra of Guerrero where Lucio once roamed.

Others on the list released two years ago by the CISEN, Mexico’s lead anti-subversion intelligence-gathering apparatus, include the largely-disarmed Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), an indigenous formation that rose in Chiapas in 1994; the Jose Maria Morelos National Guerrilla Coordinating Body, thought to be based in Puebla; and the Jaramillista Justice Commandos that takes its name from Ruben Jaramillo, the last general of revolutionary martyr Emiliano Zapata’s Liberating Army of the South gunned down by the government in 1964, which has taken credit for bombings in Zapata’s home state of Morelos.

The TAGIN or National Triple Indigenous and Guerrilla Alliance, thought to be rooted in southeastern Mexico, boasted in a e-mail communiqué at the beginning of the year that a coalition of 70 armed groups have agreed on coordinated action in 2010.

Also in the revolutionary mix are an unknown number of anarchist cells, at least one of which takes the name of Praxides G. Guerrero, the first anarchist to fall 100 years ago in the Mexican revolution.

Primarily operating in urban settings, anarchist cells have firebombed dozens of ATM machines and banks, new car showrooms, bullrings, and slaughterhouses (many anarchists are militant vegans) in Mexico City, Mexico state, Guadalajara, San Luis Potosi, and Tijuana. The U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder has just added Mexican anarchist groups to the Obama government’s terrorist lists.

Thus far, no group in this revolutionary rainbow has struck in 2010, and the window is narrowing if Mexico’s twin centennials are to be a stage upon which to launch new uprisings. If this is to be the year of the next Mexican revolution, the time to move is now.

Objective conditions on the ground are certainly ripe for popular uprising. At least 70% of the Mexican people live in and around the poverty line while a handful of oligarchs continue to dominate the economy — Mexico accounts for half of the 12 million Latin Americans who have fallen into poverty during the on-going economic downturn.

Despite Calderon’s much scoffed-at claims that the recession-wracked economy is in recovery, unemployment continues to run at record levels. Hunger is palpable on the farm and in the big cities. Indeed, the only ray of light is the drug trade that now employs between a half million and a million mostly young and impoverished people.

Labor troubles, always a crucible of revolutionary dynamics, are on the rise. A hundred years ago, conditions were not dissimilar. The fallout from the 1906-7 world depression that saw precious metal prices, the nation’s sustenance, fall off the charts sent waves of unemployment across the land and severely impacted conditions for those still working.

As copper prices bottomed, workers at the great Cananea copper pit scant miles from the Arizona border in Sonora state, went out on strike and owner Colonel William Green called in the Arizona Rangers to take the mine back. Twenty six miners were cut down and the massacre gave birth to the Mexican labor movement.

In March 2010, President Calderon dispatched hundreds of federal police and army troops to Cananea to break a protracted, nearly two-year strike at the behest of the Larrea family, the main stockholders in Grupo Mexicano Industrial which was gifted with the copper pit, the eighth largest in the world, after it was privatized by reviled ex-president Carlos Salinas in 1989. Calderon’s hard-nosed labor secretary Javiar Lozano has threatened arrest of miners’ union boss Napoleon Gomez Urrutia, now in self-exile in Vancouver, Canada.

Lozano is also deeply embroiled in take-no-hostages battles with the Mexican Electricity Workers Union (SME) over privatization of electricity generation here that has cost the union, the second oldest in the country founded during the last Mexican revolution, 44,000 jobs. A near death hunger strike by the displaced workers failed to budge the labor secretary and SME members now threaten to shut down Mexico City’s International Airport.

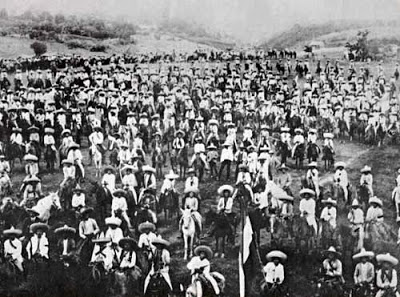

History is often colored with irony. The first important battles in the Mexican revolution were fought around Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, a key railhead on the U.S. border and a commercial lifeline to El Norte for dictator Porfirio Diaz. In skirmish after skirmish, the irregulars of Francisco Villa and Pascual Orozco challenged and defeated the dictator’s Federales and began the long push south to hook up with Emiliano Zapata’s southern army in Morelos state on the doorstep of the capitol.

Ciudad Juarez was devastated by the cruel battles between the revolutionaries and the dictator’s troops. Dead wagons plied the dusty streets hauling off the bodies of those who had fallen to be burnt out in the surrounding desert. Today, once again, Ciudad Juarez is the murder capitol of Mexico.

Over 1,800 have been killed in this border city so far in 2010, a record year for homicides, as the homegrown Juarez drug cartel and its local enforcers, the “La Linea” gang, try to defend the “plaza,” the most pertinent drug crossing point on the 1964 mile border, from the Sinaloa cartel under the management of “El Chapo” Guzman, and his local associates, “Gente Nueva” (“New People”).

Much as today when the narco kings like “El Chapo” or his recently slain associate “Nacho” Coronel are vilified by the Mexican press and President Calderon as “traitors” and “killers” and “cowards,” 100 years back revolutionaries were cast as villains and vandals hell-bent on tearing down the institutions of law and order.

Pancho Villa was universally dissed as a cattle rustler, a “bandido,” “terrorista,” and rapist. When Zapata, “the Attila of the South,” and his peasant army came down to Mexico City in 1914 to meet with Villa, the “gente decente” (decent people) locked up their homes and their daughters to protect them from the barbarian hordes.

Similarly, in 2010, the corporate press lashes out at the cartels and their pistoleros as crazed, drug-addled mercenaries who will shoot their own mothers if enough cash and cocaine are offered. Villa’s troops were no strangers to such accusations. “La Cucaracha,” the Villista marching song, pleads for “marijuana para caminar” (“marijuana to march”).

All this duel centennial year, ideologically driven leftists here have been waiting with baited breath for a resurgence of armed rebellion such as in 1994 when the EZLN rose up against the “mal gobierno” in Chiapas, or in 1996 when the EPR staged a series of murderous raids on military and police installations — but the leftists may be barking up the wrong tree.

If revolution is to be defined as the overthrow of an unpopular government and the taking of state power by armed partisans, then the new Mexican revolution is already underway, at least in the north of the country where Calderon’s ill-advised drug campaign against the cartels (in which according to the latest CISEN data 28,000 citizens have died) has morphed into generalized warfare.

Although the fighting has been largely confined to the north, it should be remembered that Mexico’s 1910 revolution began in that geography under the command of Villa and Orozco, Venustiano Carranza, Alvaro Obregon, and Francisco Madero, and then spread south to the power center of the country.

Given the qualitative leap in violence, Edgardo Buscaglia, a keen analyst of drug policy at the prestigious Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico now describes Calderon’s war as a “narco-insurgency” — a descripton recently endorsed by U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton. Daily events reported in the nation’s press lend graphic substance to the terminology.

Narco-commandos attack military and police barracks, carrying off arms and freeing prisoners from prisons in classic guerrilla fashion. As if to replay the 1910 uprising in the north, the narco gangs loot and torch the mansions of the rich in Ciudad Juarez. The narcos mount public massacres in northern cities like Juarez and Torreon that leave dozens dead and seem designed to terrorize the local populous caught up in the crossfire and impress upon the citizenry that the government can no longer protect them, a classic guerrilla warfare strategy.

One very 2010 wrinkle to the upsurge in violence: car bombs triggered by cell phones detonate in downtown Juarez, a technology that seems to have been borrowed from the U.S. invasion of Iraq (El Paso just across the river is home to several military bases where returning veterans of that crusade are housed). Plastique-like C-4 explosives used in a July 15th car bombing that killed four in downtown Juarez are readily available at Mexican mining sites.

Further into the interior, commandos thought to be operating under the sponsorship of the Zetas cartel, have repeatedly shut down key intersections in Monterrey, Mexico’s third largest city and the industrial powerhouse of the nation, with stolen construction equipment and stalled buses and trailer trucks purportedly to clear surrounding highways of traffic for the movement of troops and weaponry into this strategic region.

Now the narco-insurrection has invaded the political realm as manifested by the assassination of the one-time ruling PRI party’s front-running candidate for governor of Tamaulipas state in July 4th elections. But party affiliation doesn’t seem to be a determining factor in this ambience of fear and loathing. The kidnapping of right-wing PAN party Padrino Diego Fernandez de Cevallos, one of the most powerful politicos in Mexico and a possible presidential candidate in 2012, must send chills up and down the spines of Calderon and his associates.

Who actually put the snatch on “El Jefe” Diego remains murky. The Attorney General’s office is now pointing fingers at the Popular Revolutionary Army, which is active in the Bajio region where the PANista was taken last May 14th. In 2007, the EPR claimed credit for the bombing of PEMEX pipelines in Guanajuato and Queretero in retaliation for the disappearances of two of its historical leaders.

The Mexican military has long calculated the eventual “symbiosis of criminal cartels with armed groups that are disaffected with the government” (“Combat Against Narco-Traffic 2008″ issued by the Secretary of Defense).

Fifty thousand of the Mexican Army’s 140,000 troops and large detachments of Naval Marines are currently in the field against the narco-insurrectionists. With an eye to the eventual “symbiosis” of the drug gangs with armed guerrilla movements, the U.S. North Command which is responsible for keeping the North American mainland free of terrorists and regards Mexico as its southern security perimeter recently sent counterinsurgency trainers here to assess threats — their visit was confirmed at a Washington D.C. press conference July 21st by Under-secretary of Defense William Wechsler.

Meanwhile, the military is setting up new advance bases in regions where there have been recent guerrilla sightings such as the Sierra Gorda, strategically located at the confluence of Queretero, Guanajuato, and San Luis Potosi states.

Leftists who have been awaiting a more “political” uprising in 2010 are not convinced by Buscaglia’s nomenclature. A real revolution must be waged along ideological and class lines which the narco-insurrection has yet to manifest. Nonetheless, given the neoliberal mindset of a globalized world in which class dynamics are reduced to market domination, the on-going narco-insurrection may well be the best new Mexican revolution this beleaguered nation is going to get.

[An abbreviated version of “The Next Mexican Revolution” appeared in the Guardian (London, U.K.) September 13, 2010. Note: John Ross’s cancer has returned and he is suspending publication of his column while he undergoes chemotherapy in San Francisco. He can be reached at johnross@igc.org. Readers who crave Ross’s words are advised to consult El Monstruo: Dread and Redemption in Mexico City (Nation Books 2010), available at your local independent bookstore.]