The book reads like a peremptory strike meant to deter future biographers.

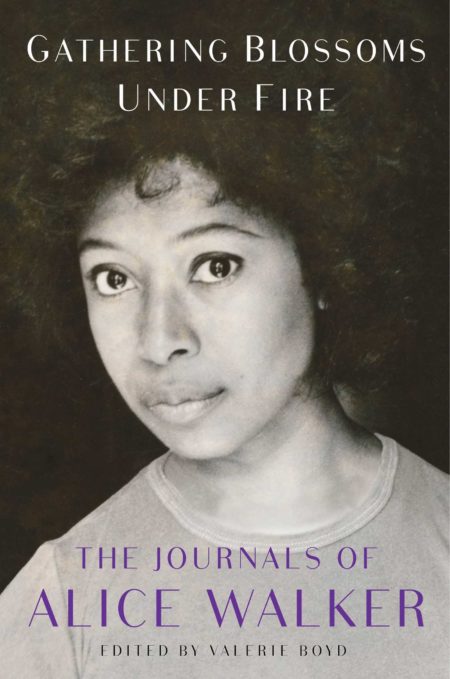

Before the advent of Black Lives Matter, Me Too, and the most recent generation of Black writers, such as Jesmyn Ward and Edwidge Danticat, there was Alice Walker, a Georgia-born novelist, poet, and short story writer who has lived most of her adult life under the radar in northern California. According to Gathering Blossoms Under Fire (528 pages; $37.50), an edited selection of entries from her journals—to be published by Simon & Schuster later this year—she first bought land in Mendocino County in 1980.

She has lived there ever since then and at her other houses in Mexico and San Francisco. In Mendocino, she has planted trees, grown vegetables, relaxed in hot tubs, welcomed lovers both male and female, friends both white and Black, and made space for her daughter, Rebecca, whose father, Melvyn Leventhal, is Jewish and a lawyer and Walker’s one and only husband. In Mississippi, in the 1960s, they were perhaps the only interracial married couple. They divorced many years ago. This February Walker will be 78.

To her credit, she does not claim to have jump-started the Black Lives Matter and the Me Too movement, though she applauds her own efforts to desegregate the segregated South, combat racism, sexism, ageism, and imperialism. She also applauds herself, though she also rakes herself over the coals and finds flaws in nearly every corner of her life. No biographer is likely to rake Walker over the coals more thoroughly than she rakes herself.

Gathering Blossoms Under Fire reads like a peremptory strike meant to deter future biographers. There are bound to be more than one, if only because Walker’s publishers will want a biography that will keep Walker’s name alive and her work in print.

I’ve heard Walker speak twice: once at a graduation ceremony at Mendocino High School when she told seniors, “Be an outcast,” “Be nobody’s darling” and “take the contradictions of your life and wrap them around you like a shawl”; and at the Peacemaking Conference in San Francisco when she shared the stage with the Dalai Lama and said, “At some point you must take your bleeding heart and look at the blue sky from the other side of the hill.”

For years, I read all of Walker’s published work: novels,

stories, poems, and nonfiction.

For years, I read all of Walker’s published work: novels, stories, poems, and nonfiction. Then, in the early 1990s, and with the publication of Possessing the Secret of Joy I stopped. Her titles, including Possessing the Secret, The Way Forward is with a Broken Heart and Hard Times Require Furious Dancing, sounded like slogans and I wanted more than slogans. Still readers have kept going back to Walker for more advice.

According to her current publishers, Simon & Schuster, her books have been translated into more than two-dozen languages and have sold more than ten million copies. As this volume shows, Walker has been an adept salesperson for herself, her work, and her causes, including the fight against female genital circumcision or “mutilation,” as its often called.

Some intimate, personal details in Walker’s life must not have made it into print, though it’s challenging to imagine what they might have been. Walker kisses and tells, and then draws a curtain. It’s likely that she has not seen fit to publish all her feelings about some people, including the avant garde Black writer Ishmael Reed, the author of Mumbo Jumbo and other experimental works who has badgered Walker for years, and has accused her of carrying out a vendetta against Black men.

Gathering Blossoms Under Fire suggests that Walker has not liked men ever since a brother accidentally shot her in one of her eyes, a traumatic event in a childhood surrounded by poverty in rural Georgia. She seems to have healed from the injury, though she doesn’t want to let go of it emotionally and psychologically.

Walker wants to like men and tries hard to like them.

Walker wants to like men and tries hard to like them. She wants to love every living creature, whether they’re male, female, trans, Black or white, old or young, rich or poor, human or animal. If she was a Christian, one might say she has ascribed to the brand of Christianity, as preached by Dr. Martin Luther King, jr, an early anchor in her life. But she’s not a Christian. For a long time, she has believed in what she calls “The Great Spirit” and “The Goddess” whom she frequently evokes.

Like her many fans and supporters, who have made her a best selling writer and a guru, Walker has practiced a New Age American version of paganism and Buddhism. Into that cauldron she has added psychotherapy, herbalism, and the questing energy of the back to the land movement that brought caravans of countercultural folk from Berkeley and San Francisco to Mendocino and Humboldt in the 1960s and 1970s.

At the end of this book, Walker expresses surprise and pleasure that she has found herself in a community of hippies. But to an attentive reader it’s not surprising, much as it’s not surprising that she became a lover of women. Women-identified women will probably take this book to heart. It might also encourage them to keep a journal, tell the truth, and shine a light into every dark corner of their existence.

Black men like Ishmael Reed and Robert Allen, a longtime lover and a father of the Woke movement, will probably want to read about themselves. I couldn’t put the book down, not for long. It appealed to the voyeur in me. I also found Gathering Blossoms narcissistic, romantic, and incredibly obsessive and compulsive, the same reasons that kept me turning pages.

What I like the least about the book is the author’s penchant for placing herself in a fairy tale that provides an escape from pandemics, homelessness, and the insanity of the world, no matter what country one inhabits. “Grow up,” I wanted to say time and again. Walker knows that she has manufactured her own fairy tale and placed herself at its center. She’s selfish for 500-pages. Some readers might not get to the end. Those who first embraced The Color Purple, Walker’s Pulitzer Prize winning novel, might go with her program and choose to be as selfish and as introverted as she.

[Jonah Raskin, a regular contributor to The Rag Blog, is the author of Beat Blues: San Francisco, 1955, a novel.

- Read articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog and listen to Thorne Dreyer’s Rag Radio interviews with Jonah.