For those who lived through the era and still care about issues of class, race, and gender, ‘Highway 61’ is the book to read about American music.

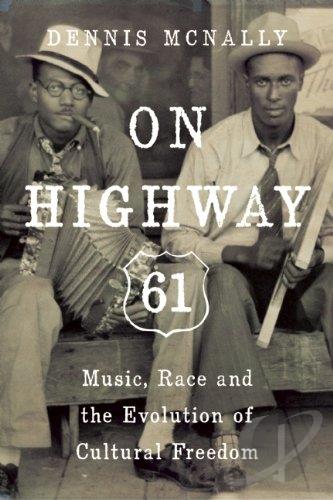

[On Highway 61: Music, Race and the Evolution of Cultural Freedom by Dennis McNally (October 2014: Counterpoint); Hardcover; 384 pages; ; $28.]

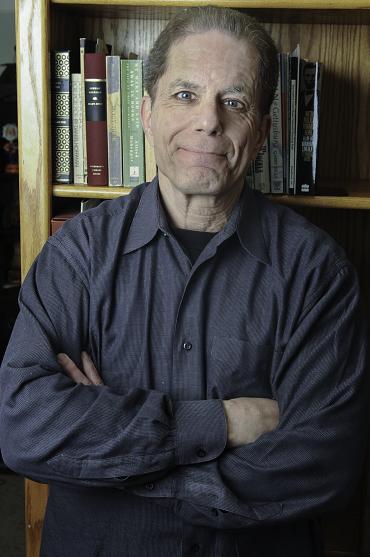

Dennis McNally’s publisher might have persuaded him to call his new book A Dead Head Looks At American Music, or The Head Dead Head’s Guide to Jazz, the Blues and Bob Dylan. After all McNally served for many years as the Grateful Dead’s publicist and historian. The author of A Long Strange Trip: The Inside History of the Grateful Dead, he knows the Dead and the Deadheads, too.

His forte as an author lies in his ability to look back at the history of American music through the eyes of the Grateful Dead and from the perspective of the cultural upheavals of the Sixties.

McNally is far more than a veteran Dead Head, however. His Desolate Angel: Jack Kerouac, The Beat Generation, and America is probably the best biography of the King of the Beats, though it was published in 1979, long before Kerouac’s letters and journals were available to scholars. In Desolate Angel, McNally writes from the heart and situates Kerouac at the heart of American culture and history.

He’s a cultural historian again in his new book, On Highway 61, that connects roots music to race, class, and gender. McNally is not the first to cover all or part of the territory. Greil Marcus, the author of Mystery Train and The History of Rock ‘n’ Roll in Ten Songs, has written insightfully about the blues and rock ‘n’ roll and McNally acknowledges his contributions.

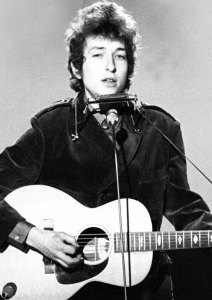

McNally is unique in that he’s embedded in the tumultuous life of the Sixties. The era is a part of him. In the chapter entitled, “Robert Zimmerman becomes Bob Dylan,” he explains that in the year 1960 America was on the cusp of profound social change. “Politics and the personal coalesced,” McNally writes. “Authenticity was everything.” He knows whereof he speaks.

In that same chapter he mentions two key events that took place in 1960 and that suggested both the rambunctious road that the United States would take and the overtly topical direction that Dylan’s brand of folk music would follow. The two events McNally mentions are the visit to San Francisco of the House Committee on Un-American Activities, better know as HUAC, and the start of the sit-in movement in Greensboro, North Carolina. Both augured political and social change.

Dylan arrived on the scene, McNally suggests, just in the nick of time to witness the break-up of the ideology of the Cold War that kept Americans in fear. At the same time, he appeared in time to observe the birth of a defiant generation, unafraid to take on the power of the segregated South and the White House. While all that was happening, Dylan was also discovering the writing of the Beats. After reading Kerouac’s book of poems, Mexico City Blues, he exclaimed, “It blew my mind.”

McNally takes readers on a long strange trip and shows how Dylan blew the collective mind of his own generation and the mind of an older generation who’d grown up on Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin. McNally knows heaps about particular songs such as “You Can’t Keep a Good Man Down,” “Sinner Man,” and “Ballad of a Thin Man” in which Dylan captured the essence of the generation gap in the refrain, “something is happening here/But you don’t know what it is/Do you, Mister Jones?”

The Head Dead Head and King of Kerouac scholars also knows a ton about history and culture in the American South, the region that gave birth to the blues and to jazz, the two art forms of African-Americans that transformed the entire society and that found devoted listeners around the world.

McNally also knows volumes about the lives of legendary American bluesmen, blues women, and bandleaders from Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington to Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith. Yes, the women of the blues are here in force, along with their male counterparts. Some of McNally’s best writing appears in the chapter on Rainey and Smith. In that same chapter he goes to the heart of race and sex in America. “Women performers could be sexy or romantic, or simply emotive,” he explains. “Whereas a sexy black man pushed buttons deep in the American psyche.”

McNally also knows that some things aren’t known or even knowable. Indeed, as he points out, no one knows for sure where Robert Johnson, the King of the Delta Blues, was buried or why he died.

“Mystery begets mystery,” McNally writes. Some of the past that he writes about is all too clear and all too sad, including the stormy relationship between the white Texas-born musicologist and folklorist John Lomax and the black folk singer who was born Huddie William Ledbetter and who would become renowned as Lead Belly, the master of the 12-string guitar.

The story of Lomax and Lead Belly might serve as an emblem of the tangled knot that has connected white authors, promoters, and fans to authentic black artists who have often been misrepresented and exploited. “Lomax ignored many academic standards,” McNally explains. “He edited songs without saying so, cited no sources and seemingly did a lot of his research by mail.” But his Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads made him famous. And so did his recordings of Lead Belly.

In Highway 61, McNally sets the record straight about Lead Belly and Lomax and about Bob Dylan and his first real love, Suze Rotolo, who grew up in a left-wing American family; Joan Baez, who was left out in the cold; and Allen Ginsberg, who saw Dylan as the heir to the Beats.

The book also documents the influence of the Civil Rights movement on Dylan’s brand of folk music. His funereal song, “Only a Pawn in Their Game” — written in the immediate aftermath of the assassination of Medgar Evers — includes the refrain, “And the Negro’s name/Is used it is plain/For the politician’s gain.” Change the word Negro to black or to African-American and Dylan’s lyrics are as timely now as they were 50 years ago.

McNally might have wrapped up his story with the Grateful Dead and its lyricist Robert Hunter. But he’s already said nearly everything he’s wanted to say about Jerry Garcia, Phil Lesh, Mickey Hart, Bob Weir and Bill Kreutzmann. Ending his “odyssey through American culture,” as he calls it, with Bob Dylan feels right. So does McNally’s closing tribute to the Sixties.

“The impulse toward liberation that emerged in that era endures in a dozen causes,” he writes. “The environmental movement, the feminist movement, the pursuit of rights for all those who do not live in conventional sexual roles.”

McNally adds, “That history is still being written.” One might borrow from Chuck Berry, who sang, “Hail, hail rock ‘n’ roll,” and add, “Hail, hail the Sixties.” For those who lived through the era and who still care about issues of class, race, and gender, Highway 61 is the book to read about American music, the book that will awaken memories, stir the heart, and evoke the sounds of Bessie Smith, Lead Belly, and Bob Dylan

Read more of Jonah Raskin’s writing on The Rag Blog.

[Rag Blog contributing editor Jonah Raskin, a professor emeritus at Sonoma State University, is the author of the forthcoming book, A Terrible Beauty: The Wilderness of American Literature.]

Interesting article, definitely made me curious about McNally’s new book. Just for the record, though, Mr. Raskin needs to brush up on his Grateful Dead:

Phil’s name is spelled Lesh, not Lesch.

Robert Hunter is the band’s lyricist, not a playing member.

The playing and founding member of the band he left out is Bob Weir.

Now I have to go get the book.

Thanks, Matt. We’ve corrected the text.

The Club Mates Travel Difference Club Mates is a professional and specialist provider of holidays, touring and travel for people with a disability or maybe just those individuals who require any level of support or companionship when travelling anywhere nationally or internationally.

http://www.clubmatescruising.com