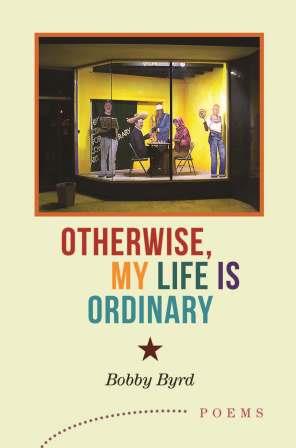

In ‘Otherwise, My Life Is Ordinary,’ Bobby Byrd has taken ordinary things and people and turned them into something extraordinary.

[Otherwise My Life Is Ordinary: Poems by Bobby Byrd (May 2014: Cinco Puntos Press, El Paso); Paperback; 121 pp; $15.95.]

British poet Tony Connor once told me, “A poet at 17 is 17. And a poet at 71 is a poet.” Connor published his first book of poetry, With Love Somehow, in 1962 at the age of 32. I met him in 1965 when he published his second book, Lodgers. His eighth book, Metamorphic Adventures, came out in 1996. Connor has stayed the course.

So has Bobby Byrd, the Memphis-born poet who has lived in El Paso, Texas, with his wife and children, since 1978. Soon after the Byrds arrived in El Paso, Bobby and his wife, Lee, founded Cinco Puntos Press, which has published half a dozen of Bobby’s books, including White Panties, Dead Friends & Other Bits and Pieces of Love; The Price of Doing Business in Mexico; On the Transmigration of Souls in El Paso; and most recently, Otherwise, My Life Is Ordinary. Son Johnny Byrd runs the press these days.

His dad, Bobby Byrd, is a kind of Texas wise guy and a man of wisdom, too, a Zen Buddhist priest, in fact, since 2010. Kinky Friedman would probably like his new book of poems; so would Willie Nelson. The Dalai Lama might get a kick out of them.

Byrd writes about his own life, his boyhood and youth, getting old, and about his time in Memphis, New York, and Texas. His poems aren’t obscure or difficult in the way that much contemporary poetry is intentionally obscure. Byrd means to communicate. He wants to be understood and to reach readers.

But he’s also about digging deep inside and expressing himself, which he does in the introductory essay, “How Did this Happen?,” and in the 49 poems that sound as though the author is in the same room talking to me, to you, and to anyone who will pause a moment, slow down, and listen.

Byrd has done a lot of listening all through his life. He’s listened to black music, Latin rhythms, and to the ways that ordinary people speak in El Paso and elsewhere. In “Benny Has Gone to Live with the Angels,” Byrd’s neighbor, Cecelia Ledesma, tells him that Benny, her dead husband, “still pulls at the sheets.” And then, the next night, Byrd himself hears Benny arguing with an “old vato.”

Byrd writes fearlessly. He’s not afraid to call a waitress “bitchy,” to describe Walt Whitman as “an old fart,” and to toss around the words fuck and fucking, which still can’t be broadcast on National Public Radio. No, you won’t hear these poems on NPR, perhaps because the author writes explicitly about sex in “Lying in Bed After Lovemaking” and because he doesn’t have a kind word to say about President Richard Nixon and President George Bush, both of whom flicker across these pages.

He’s explicitly and overtly political in “Imperialism in the 21st Century: The Bush Years.” Last time I listened to NPR, I realized that it wasn’t proper to say imperialism and George Bush in the same breath.

Byrd keeps coming back to poetry and to his sense of himself as a poet, as though he has to remind himself that he’s a real poet in the wide open spaces of Texas, an unlikely place for a poet like himself who identifies with the Spanish surrealist, Garcia Lorca, in “Channeling Garcia Lorca in Van Horn, Texas.” The poem begins, “one reason to go to Van Horn is to make poems.”

It comes to a close with the provocative line, “Austin is a shitty place to make poems.” Byrd is in your face. He’d like to shock you and offend you and then be your best friend, even if you are from Austin, New York, or Memphis, three American cities that he revisits in Otherwise, My Life is Ordinary.

If this book represents Byrd fairly, then his life probably is ordinary. But he has taken ordinary things and people — beans and plums, the bitchy waitresses, and the haunted widow — and turned them into something extraordinary.

Like Tony Connor, Bobby Byrd is a poet and a survivor, too. He’s an ordinary man who writes poems to survive and he survives because he makes uncommon poetry that expresses the 1960s utopian dream. “I want to walk in Peace and Beauty,” he writes in a long poem in which he agonizes about the spate of mass murders in Juarez, Mexico. He adds, “I want to be here next year, / Digging holes, planting trees, making prayers.” And making more poems, too, one hopes.

Read more of Jonah Raskin’s writing on The Rag Blog.

[Jonah Raskin is is the author of six poetry chapbooks, including Rock ‘n’ Roll Women, and a contributing editor at The Rag Blog.]

Thanks, Jonah. Just added it to my summer reading wish list.

Dear Jonah, damn, sometimes things fall through the cracks. Like right now. I’m so delighted and proud to read this review. Many thanks.

Bobby

Thanks for spreading the word about this fine poet.