A review of Susan Reverby’s new book about former leftist fugitive Dr. Alan Bergman.

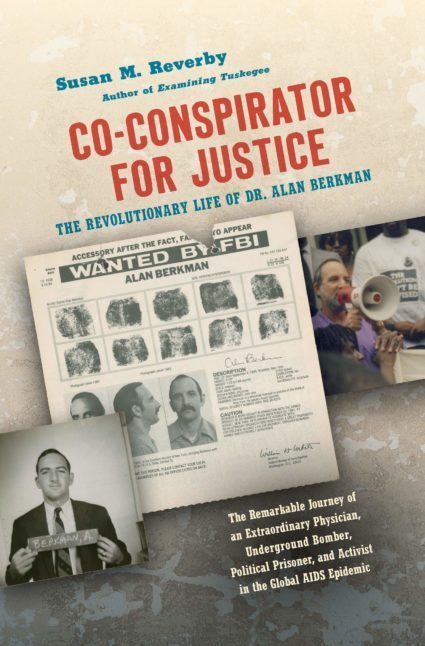

Co-Conspirator for Justice: The Revolutionary Life of Dr. Alan Bergman by Susan M. Reverby (2020: University of North Carolina Press; $30)

SONOMA COUNTY, Calif — Marilyn Buck doesn’t show up in Susan Reverby’s biography of Dr. Alan Berkman (1945-2009) until about page 100 in a 300-page book, when she hooked up with members of the Black Liberation Army (BLA). From that decisive moment in the 1970s, until her death from cancer in 2010, Buck played a vital role in Berkman’s life — they were briefly lovers — and also in the armed underground groups, including the BLA, to which they were affiliated.

Like her, Berkman died of cancer. Like her, he served time in prison, though not as long. Like her, he thought of himself as a revolutionary. Unlike her he was Jewish, Ivy League, and East Coast all the way.

Born in 1947 in Temple, Texas, and the daughter of a liberal Episcopal minister, Buck belonged to SDS, was a volunteer at the original Rag in Austin, wrote for New Left Notes, worked with Third World Newsreel, and in 1979 presumably helped BLA member, Assata Shakur, escape from prison.

In a 2010 article for The Rag Blog, Mariann G. Wizard noted that she and Buck had been friends since 1966. Wizard added that while Buck had been arrested and sentenced to 10 years in prison for buying explosives under an alias, her real “crime” was that she “gave material support to Black people to defend themselves against white supremacist attacks and the racist police.” That’s one way to put it.

Dr. Berkman treated Buck for an accidental gunshot wound.

Much the same defense could be made for Dr. Berkman, who treated Buck for a self-inflicted (accidental) gunshot wound when she was wanted by the FBI, following a botched attempt to rob a Brinks armored vehicle when a guard and two police officers were shot and killed by the would-be thieves.

Berkman didn’t report the medical help he provided Buck — a violation of the law. Later, he refused to honor a subpoena that called him to testify before a grand jury investigating Brinks and the links between white radicals and the BLA. Berkman served seven months in the Metropolitan Correctional Center in New York. Soon afterward he went underground. The government upped the charges against him to accessory to bank robbery and murder. For several years he was wanted by the FBI. During that time he and his confederates robbed a Connecticut supermarket of $21, 480. They were armed and they tied up the manager of the store.

Codefendants in Resistance Conspiracy case, 1988. Marilyn Buck seated far left, Alan Berkman seated far right 1988

After his arrest, Berkman was sentenced to 10 years in prison. He served eight. After his release, he wrote a letter for Buck, who was serving a life sentence, in the hope she might receive parole.

‘Marilyn, like myself, made serious mistakes that impacted on others.’

“Marilyn, like myself,” he explained, “made serious mistakes that impacted on others in our effort to achieve a more just society. But our motivation was truly social justice and not a desire to be violent.”

Berkman was far more self-critical in a statement he made in 1994 to a New York Times reporter. “There is plenty to learn from all the mistakes we made,” he said. “Power is corrupting. And the use of violence is a form of power. People motivated to stop the suffering of others have to be careful not be caught up in the same dynamics.”

Reverby doesn’t include this trenchant comment in her biography of Berkman, though she offers hundreds of quotations from him, including one to a friend named Ann Morris. “I, after years of being in small political groups where we discussed/ argued/ did criticism-self-criticism, real or imagined, no longer want to engage in that kind of dialogue,” he explained. “Increasingly in my life, I’ve grown to recognize & respect differences & don’t feel compelled to argue about it.”

As Reverby shows, Berkman was hung up on violence time and time again. She’s hung up on Berkman, whom she knew from an early age and then parted ways because of what might be called “irreconcilable differences.” Reverby doesn’t seem to know what to make of Berkman, not even after writing her book and living with the material for years. She calls him a “revolutionary,” a “co-conspirator,” “extraordinary,” “an underground bomber, political prisoner and activist in the global Aids epidemic.” That’s more than a mouthful.

Berkman called himself “an adventurist” which seems to hit the nail on the head.

In the acknowledgments at the end of the book, she says that writing “it was hell” and that it “may be my last.” She goes on to try to understand why. Two reasons she provides: one feeling “guilty” for not having done more for Alan when he was “incarcerated and sick”; and second “being romantic about Alan’s commitments and action.” She goes on to say that as she watched his story unfold she “just wanted to yell at him to stop.”

She goes back and forth from hero

worship to demonizing.

Reverby is both too close to Berkman and too far away, too critical and too empathetic. She goes back and forth from hero worship to demonizing. At one point she even uses Frederick Douglass — who refused to support John Brown and his raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859 — to berate him. A love letter might have been better than this biography which goes back and forth from love to hate.

After reading the book, I called and spoke with a former member of the Weather Underground who was a fugitive all through the 1970s. I told the ex-undergrounder that I didn’t understand how and why Berkman and his confederates could repeat the same mistakes that Weatherman and the Weather Underground had made. From the other end of the phone conversation came this comment, “Yes, they went back to where we had been in 1969 and 1970, and followed more or less the same errors we had made.” I said, “maybe they thought they could do it the right way.”

“Perhaps so,” the ex-underground replied. “But they ended up doing it the wrong way all over again.”

I understand Mariann Wizard’s affectionate comments about Marilyn Buck after her death from cancer in 2010: a sad sad end to a complicated life.

We need to be kind to comrades who have

taken wrong turns.

Yes, we need to be kind to comrades who have taken wrong turns, committed acts of violence and caused harm to themselves and to their family members and friends. Demonizing the comrades won’t help. But we also have a responsibility to tell the truth, to think about future generations and how we might help and not hinder. It’s too bad and very sad that it took Berkman years and years to get away from criticism-self-criticism sessions when he argued and discussed fine points of ideology and tactics and strategy and didn’t accept honorable differences of opinion.

I was there once upon a time. I did that. I don’t wish it on anyone.

Susan Reverby knows what really happened with Alan Berkman, Marilyn Buck and their comrades, but she has not told readers all that she knows. There are too many omissions. Everybody, except for Dave Gilbert, is out of prison and he can’t be punished more than he already has been. There is nothing to protect, except perhaps egos and pride.

At this time and place in history there’s no valid reason to hide the truth or truths. We’re old enough and wise enough, I think, to hear it straight and not have to read about “the miracle” of Alan Berkman’s “resurrection.”

Even when Berkman did good work around AIDS and HIV, he made statements that seem off-base. He argued against “scientifically” colonizing Africa, which makes some sense but he added, “Let Africa take care of itself.” In fact, African nations needed medical help and expertise from the U.S. and other countries. There were ways to aid Africa without colonization. U.S. health workers have been doing that for decades.

In her acknowledgements, Reverby says, “I tried really hard to make this appeal to another generation.” I am sure she did. But her biography of Alan Berkman doesn’t speak the language of the young people who have been in the streets of American towns and cities this spring and who don’t need illusions and lies and the obfuscation of past struggles.

“The use of violence is a form of power,” Berkman explained. “Power is corrupting.” It was in his day. It still is today. He might not have committed acts of violence, but he was associated with people who did. He helped to enable them. That, too, was a kind of sickness.

[Jonah Raskin, a regular contributor to The Rag Blog, is the author of For The Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman and American Scream: Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’ and the Making of the Beat Generation.]

- Read articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog and listen to Thorne Dreyer’s Rag Radio interviews with Jonah.

Hunh. Well, it’s a shame it’s not a better book, Jonah. I’ve always been mildly curious about Alan Berkman, mainly in terms of how Marilyn and her associates knew to go to him when Marilyn shot herself in the knee during the Brinks job screwup. She and I never discussed him, since all of our contacts after her first conviction were under her conditions of incarceration or fugitivity.

I believe that the urge to “educational,” “exemplary,” demonstrative violence stems from despair, and despair from the lack of a class analysis and program. Since other analyses and programs have been found to be insufficient time and again, it is curious to me that this blind spot exists.

Crimes against Black people are reprehensible, ongoing, and an integral part of social control. Marilyn Buck’s ability as a white middle class woman to buy guns and ammo enabled Black activists in California to put up some resistance to police violence and if I’d known what she was doing then I woulda helped her.

But Black people will not find liberation short of a working class revolution.

Hopefully the current round of protests can make state-sanctioned police murder less common. Hopefully some policing reforms can be achieved. Most hopefully, some new alliances can be forged and transracial trust established on person-to-person terms, pushing class solidarity forward and real change “towards Bethlem to be born.”

Revolution is a rough beast. Respect to all those who have had the courage to try to ride it, even the ones who got throwed.

I like what you have to say. Right on. I used to chant “Off the Pig” and meant it. The current wave of protests shows to me once again the importance of being in the streets and protesting in the streets, not going underground and making bombs. I was in and around Weather for years and while I sometimes defended their actions I also felt that their energies would have been better used in mass political actions not in occasional symbolic explosions with TNT. I heard a cop say something on TV last night about how at 3 am if you have been robbed or assaulted you want the cops to show up. No thanks. The cops are the last people I want to show up at 3 am at my house. Solidarity forever.