Jonah Raskin will discuss this article and related issues on Rag Radio, Friday, Nov. 24, 2-3 p.m. (CT) on KOOP 91.7-FM in Austin or streamed at KOOP.org.

For the past 600 years and maybe far further back in time than that, indigenous people all over the world have taken a terrible beating, though they have also survived. Novelists, poets, painters, playwrights, and filmmakers have told that story of genocide and resistance in its many iterations over and over again, and still the wars go on. David Grann tells a small part of that global phenomenon in his nonfiction book, Killers of the Flower Moon, a bestseller. Now, famed director Martin Scorsese has adapted parts of Grann’s story for a long movie that describes the war that white settlers, businessmen, and lawmen waged in the 1920s in the state of Oklahoma against a Native American tribe called the Osage.

The Osage called the war that was waged against them a “Reign of Terror.” When oil was discovered in Osage territory in Oklahoma, the Indians suddenly became wealthy. In many ways they assimilated white values, without totally surrendering their own heritage and language. Both resistance and compliance went on at the same time.

Some Indians built mansions, hired servants and drove expensive cars. That’s a part of the historical record. In the eyes of many whites on the Oklahoma frontier in the 1920s, Indians with money were Indians who had no right to exist.

Hence the Reign of Terror which took the lives of dozens of Osage.

Hence the Reign of Terror which took the lives of dozens of Osage and perhaps far more than that number. No one kept an accurate record of the number of mostly Indian women who were shot to death, poisoned, and blown to bits with dynamite. The whites lied, conspired, and tried to cover-up their crimes.

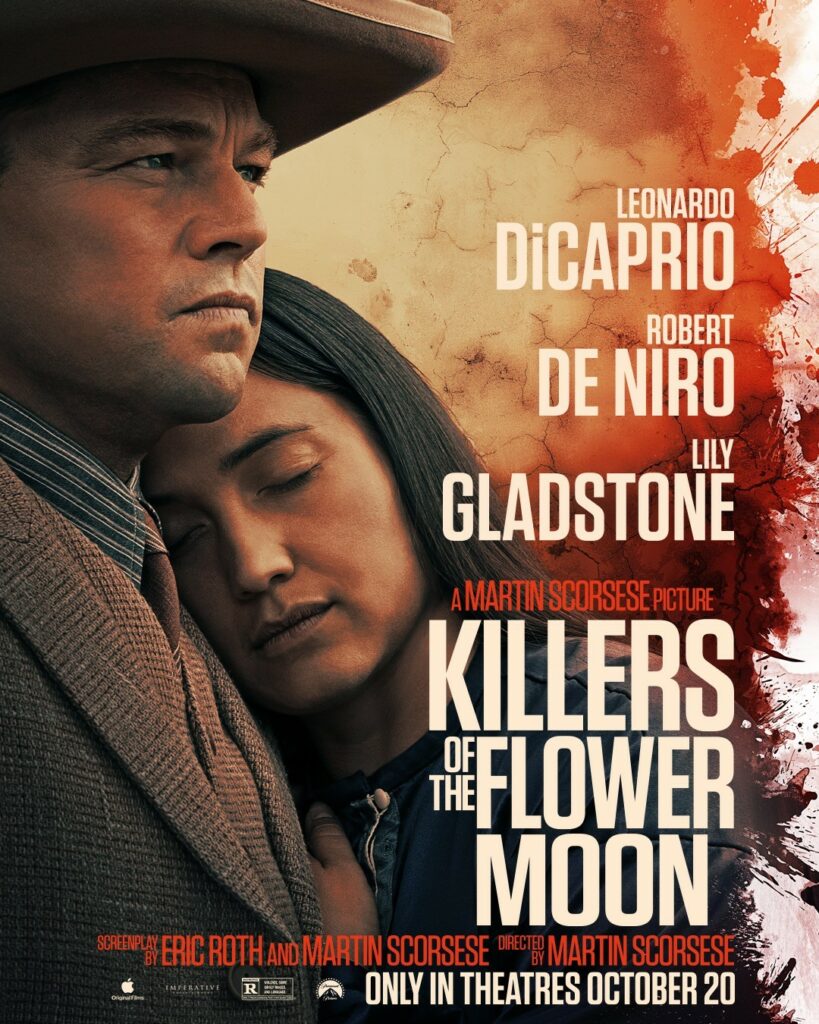

Scorsese’s long (3 hrs 26 min) movie offers a somber tale of romance and murder that connects two star-crossed lovers: a greedy World War I vet named Ernest (Leonardo DiCaprio,) who craves money and lots of it; and Molly, a proud and dignified woman who belongs to the Osage, becomes Ernest’s wife and the mother of their children.

She loves him and he claims he loves her, though he’s under the thumb of a sinister uncle. Ernest sets about trying to poison Molly and inherit her property.

Lily Gladstone reprises to perfection the role of the Native American beauty once played by white actors.

Lily Gladstone, who is of Piegan Blackfeet, Nez Piece, and European heritage, reprises to perfection the role of the Native American beauty once played by white actors in movies like The Searchers (1956) which stars John Wayne, Natalie Wood, and Henry Brandon as Chief Cicatriz.

Grann’s book, which has been translated into Spanish, French, and more, is subtitled “The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI.” It has enough material for several movies. In Scorsese’s telling, the clean shaved G-Men — who work for a young J. Edgar Hoover and for the Bureau of Investigation, a forerunner of the FBI — are heroic, though they aren’t glamorized. The G-Men solve the mystery of the brutal murders and help send the guilty parties to prison. That, too, is part of the historical record.

Given his long fascination with crime and criminals (Goodfellas, Casino, Gangs of New York, and The Irishman) it’s not hard to understand why Scorsese was drawn to the story of gangland style multiple murders on the oil-rich prairies, along with the cinematic bonus of good guys in law enforcement.

Perhaps Scorsese wanted to show that he has a social conscience.

Perhaps Scorsese wanted to show that he has a social conscience and wanted to do right by the Indians. But if that were true, he might have placed the Indians, not the white men or the G-men from Washington, at the center of his drama. Molly, not Ernest, could have been the star of the show.

At a press conference to publicize the movie, Scorsese presented himself as a friend of the Osage who had their support all through the project. But an Osage who served as a consultant on the film noted that the story is told from the perspective of the white man who marries Molly and tries to kill her. “That’s not love,” he said. “That’s beyond abuse.” He added that “it would take an Osage” to tell the story.

The title for the book and the movie comes from the Osage observation and saying that the first brightly colored flowers of Spring perish with the arrival, under a full moon, of taller and hardier plants that steal their light and water and so they perish until they are reborn the next year. Perhaps it’s a parable about the cycles of nature and human history.

Perhaps it’s a parable about the cycles of nature and human history.

Years ago, when I protested against the policies of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and the role of the FBI at Wounded Knee in the early 1970s, I wrote and published a fictionalized account of the life of Dennis Banks, a leader of the American Indian Movement (AIM), along with Russell Means and Leonard Peltier, who is still in prison after nearly 50 years behind bars. I gave my illustrated book to an AIM member hoping for an honest opinion. “Your story is awfully grim,” he said, “There’s no laughter. You know, Indians have a terrific sense of humor.”

Martin Scorsese doesn’t seem to know about Indian comedy. Sherman Alexis, a member of the Spokane tribe in Washington State, does. Two of his books, The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven and The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, have entertained me and many other readers for decades. Alexis’ titles alone provoke laughter.

Now, during November — Indigenous Peoples’ Month — we might remember that Indians laugh as well as cry, that they can be as wily as coyotes and as wonderful story tellers as the land, the sky, the rivers, and the lakes themselves. Scorsese’s movie doesn’t conclude with laughter, but rather with a lyrical view from above the earth, and with an accompanying soundtrack of an Indian drumming circle. It’s a sweet, spiritual end to a grim film about the Reign of Terror waged by white men against the Osage who still live and follow tribal ways in Oklahoma.

[Jonah Raskin, a regular contributor to The Rag Blog, is the author of The Thief of Yellow Roses, 36 New Poems, available from Barnes and Noble, Amazon, and elsewhere.]

Listen to Thorne Dreyer’s Rag Radio interviews with Jonah Raskin here.

You tell it well!