A review of Glenn Silber’s and Barry Brown’s timeless documentary.

SONOMA COUNTY, California — As Austinites and their friends and comrades all across Texas know, the coasts, east and west, often get more media coverage than the heartland, and that part of the U.S. often described, unfortunately, as “fly over country.” Fly over it and much is missed. Dozens of books and films tell the story of Berkeley in the Sixties. Also, a great deal has been written about the many demonstrations that shook the nation’s capital to protest against segregation and the War in Vietnam.

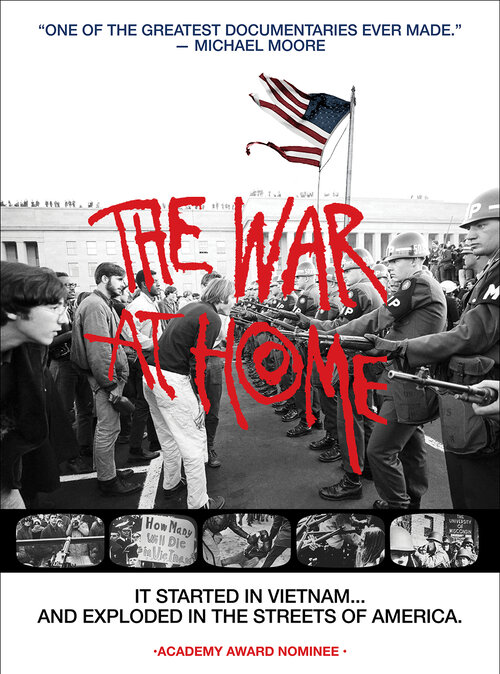

Not to explore and recount the movements that roiled towns and cities from Madison, Wisconsin to Austin, Texas, is to omit a crucial part of the story. The War at Home, a documentary directed by Glenn Silber, a veteran of CBS and ABC, and Barry Alexander Brown — and narrated by veteran journalist Blake Kellogg — lovingly follows the demonstrators who marched, leafleted, and sat down in Madison, Wisconsin.

At the end of the decade, there was a big bombing at the Army Math Research Center on the campus of the University of Wisconsin in Madison, which resulted in the accidental death of physics researcher, Robert Fassnacht. Was the explosion a fitting end to the decade or unfitting? Viewers can decide for themselves.

Originally released in 1979 and nominated for an Oscar for best documentary feature, The War at Home at 100 minutes long was recently restored to 4K, which makes the images sharper. It was re-released in 2018. That year it stunned audiences at the New York Film Festival where the festival’s director, Kent Jones, called it “one of the great works of American documentary movie making.” The images often speak for themselves, though they have been carefully selected and arranged.

Now, ‘The War at Home. is available for streaming on many platforms

Now, The War at Home is available for streaming on many platforms, including Amazon Prime and YouTube. I recommend it to veterans of the Sixties anti-war movement and to radicals of all sorts who were not yet born by 1970, the year of the big bombing in Madison, or 1975 the year when the war finally ended.

Madison put its own stamp on the movement, but it also reflected the larger nationwide movement, encapsulating and intensifying.

Indeed, the campus and the city — once described as “all-American” — provide the filmmakers with a microcosm of the nation itself. Beginning in 1960 and running to 1970, the documentary traces the evolution of the antiwar movement, including the growth of Students for a Democratc Society (SDS), whose young members wore ties and jackets and who were coaxed by the likes of Tom Hayden and others, to defy the White House and the Pentagon.

Some Sixties radicals once chanted, “Bring the War Home.” They engaged in acts of civil disobedience, carried Viet Cong flags, and chanted “Ho Ho Ho Chi Minh, the NLF is gonna win.” Still, the war came home without them. Gis brought it home, whether alive or in body bags. Reporters, doctors, and nurses brought it home. There was no way that the Vietnam War could remain far removed from the edge of American consciousness. It haunted the nation and helped to turn it upside down. For years, the war at home divided cities like Madison and Austin.

I visited Hanoi in 1995 and saw that no one really wins a war.

I visited Hanoi in 1995 and saw that no one really wins a war. The human casualties and the “collaterall damages” are immense. I came back to the States a pacifist.

Silber’s and Brown’s doc includes many of the pivotal, dramatic moments of the era, such as the protests against Dow, which manufactured napalm and that was used to wage chemical warfare against the Vietnamese.

The War at Home features Madison notables: flamboyant Mayor Paul Soglin; legendary activist Margery Tabankin; eloquent Wahid Rashad, a leader of the Black student strike in 1969; and fiery bomber Karleton Armstrong.

It offers archival footage of U.S. Senator Ernest Gruening who says, “all protest against the war… is a civic duty.” Sociology Professor Maurice Zeitlin tries to protect the protesters from the cops, one of whom says, “let’s go in and take a crack at them.”

At one point, Karleton Armstrong says, “we’ll make war on them,” meaning the warmakers. Later, he explains that he “felt shame for taking someone’s life” after the bomb blast at Army Math. Some of the slogans, such as “women say yes to guys who say no” reflect, perhaps unintentionally, the sexism of the era. Phil Ochs sings, “I ain’t a marchin’ anymore.” Thousands of students, the largely unheralded heroes of the movement, are seen marching in the streets of Madison.

On camera, presidents lie, as when LBJ says, “We seek no wider war.” Men burn their draft cards, National Guardsmen shoot and kill four students at Kent State, and finally, finally the war grinds to an end. The War at Home brings back the decade when protest flowered from coast-to-coast and from major cities to small towns. It celebrates a time we ought to remember with pride. Kudos to Silber, Brown and the whole team that made the film.

[Jonah Raskin, a regular contributor to The Rag Blog is the author of For the Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman recently translated into French and published in France under the title, Pour le plaisir de faire la révolution.]

- Read articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog and listen to Thorne Dreyer’s Rag Radio interviews with Jonah.

The bombing in Madison that Jonah Raskin mentions in his review is the back story of an excellent movie worth seeing, starring River Phoenix and Judd Hirsch among others. The title is “Running on Empty.” The screenplay, nominated for an Academy Award, was written by Naomi (Achs) Foner, a friend of both mine and Jonah Raskin’s during our college days. Naomi became better known later in her life as the mother of movie stars Maggie and Jake Gyllenhaal.

Darn it, one of my old person problems is that I can’t get the Amazon prime movies to play on my TV! Once they would, but now they won’t. I think I saw this film two or three decades ago, or more, but obviously if that’s all I can remember, I definitely need to see it again!

I find your blog to be of interest. I’m one of the original Austin hippies from the old counter-cultural days in Austin. In 1970 I was famous as “the campus minstrel” for my daily concerts at UT’s George Washington statue on the South Mall of the campus. I remember the Rag from those days. The Rag covered my initiation ceremony in 1971 when I became a Hare Krishna monk. The amazing thing about the ceremony was that we invited Austin’s mayor, Roy Butler, and he attended the function. The neighbors complained to the police about our ceremony and when the police showed up the mayor sent them on their merry way.