Marijuana has been a heated political issue in the United States for more than 100 years.

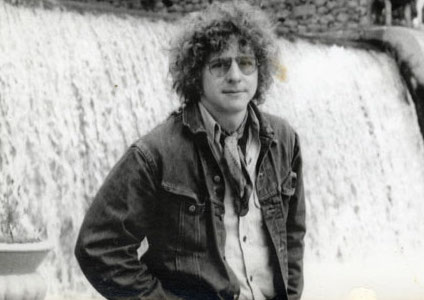

Gustin Reichbach in the ’60s. Judge Reichbach, who died in 2012, was a proponent of medical marijuana. Image from Gustin L. Reichbach Papers / University at Buffalo Libraries.

Three months before he died of pancreatic cancer in July 2012, Judge Gustin L. Reichbach published an op-ed piece in The New York Times in which he said that “marijuana is the only medicine that gives me some relief from nausea, stimulates my appetite, and makes it easier to fall asleep.” He added, “friends have chosen, at some personal risk, to provide the substance.”

What Reichbach did not say in his op-ed piece, but that almost all of his friends and family members knew, was that he had smoked marijuana for decades, before he was diagnosed with cancer in 2009, and that he enjoyed getting “high” and getting “stoned,” to borrow the vernacular.

He insisted he had written some of his best opinions under the influence of marijuana.

He even insisted that he had written some of his best opinions while he was under the influence of marijuana. Perhaps that was so. Poets like Baudelaire and Allen Ginsberg have been inspired to write some of their best poetry under the influence of marijuana, and apparently professional football and baseball players consumed it to enhance their performance on the field.

I was a life-long friend from 1967 until 2012. He was the first person I knew who smoked marijuana all day long and seemed to function better on marijuana than off marijuana. The first time I got stoned I was at his apartment in New York. I smoked with him in Brooklyn and in San Francisco. He always complained that I didn’t know how to roll a joint. It’s true. I still don’t know.

One would have thought that Gus — as Judge Reichbach was known to friends — might have come out of the “cannabis closet” before he died. After all, it was no secret that he had been arrested during the protests at Columbia and then in Chicago in 1968.

A leader of SDS at Columbia Law School, and one of the co-authors, along with Kathy Boudin, of The Bust Book, as well as a lawyer for the Black Panthers, and Abbie Hoffman, Reichbach also attained fame and notoriety as the judge who urged that prostitutes in his Brooklyn courtroom be provided with basic education about safe sex.

For his efforts, The New York Daily News called him, on the front page, “The Condom Judge.”

Reichbach never concealed his radical politics or his connection to the Yippies.

A flamboyant character, Reichbach never concealed his radical politics, his connection to the Yippies, and his unorthodox views on Cuba, Castro, Eastern European nations, and democracy. But he never publicly admitted that he smoked marijuana. In that regard, he was not alone.

Millions of Americans who have used marijuana, or “cannabis” as it is now often called, have remained in the closet rather than risk an arrest, public humiliation, the loss of a job, and a raid from “child protective services” to remove sons and daughters from pot-smoking parents and from a household in which marijuana is present. (Drug testing is still required for employment in many jobs; those who test positive for pot aren’t hired or they are fired.)

Perhaps the millions of pot-smoking citizens in the closet would rather be safe than sorry. After all, Attorney General Jeff Sessions — who once reportedly said that he admired the KKK until he heard that they smoked marijuana — has threatened to use all the force available to him to crack down on states that have legalized the kind of medical marijuana that Judge Reichbach used when he was dying a painful death.

Mr. Sessions is the medical marijuana industry’s worst nightmare.

Mr. Sessions is the medical marijuana industry’s worst nightmare. But he is only the most recent in a long and ignoble history of hideous drug warriors who have aided and abetted the formation of a society in which millions of citizens are criminalized.

Those who don’t smoke or buy marijuana probably have little or no idea of the extent or the depth of the marijuana subculture. But ask any of the thousands of criminal defense lawyers who have defended, for decades, a crowded cast of smugglers, traffickers, cultivator, wholesalers, retailers, and petty dealers. The marijuana lawyers and their clients have been in halls of justice from Miami and New York to Chicago and Dallas, where the courts have been clogged with marijuana cases that don’t get much play in the media anymore, though they once did.

Indeed, marijuana has been a heated political and social issue in the United States for more than 100 years, and it’s not likely to cool off anytime soon. In California, what started as a hippie enterprise quickly morphed into agribusiness that unleashed greed not seen since the Gold Rush of 1848-1855.

No wonder it’s called “The Green Rush,” and no wonder it has caused great environmental destruction all over the Golden State, including the pollution of rivers and streams, the illegal cutting of woods, and the use of harmful pesticides and herbicides.

Adventurers, rascals, and get-rich-quick schemers have rushed to remote California.

From all over the world, adventurers, rascals, and get-rich-quick schemers have rushed to remote California counties, bought land, upped the price of real estate, and squatted on remote, thickly forested federal lands where law enforcement can only reach them by helicopter. If nothing else, growers devised ingenious ways to evade detection and arrests.

Even before passage of the Marihuana (that’s how it was spelled) Tax Act of 1937 that made marijuana illegal by federal law, marijuana had been under attack in states all over the country. California, which was the first state to legalize medical cannabis in 1996, was also the first state to outlaw cannabis in 1915. Other states followed California’s example and prohibited it in the twentieth century.

From the beginning, the laws against marijuana were used selectively to arrest and punish people of color, whether they were Mexicans, African Americans, or Indians (from India) who worked in agriculture and on the railroads, especially in California.

She showed how marijuana laws have been used to target millions of young black men.

In her powerful, best selling book, The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander showed how marijuana laws have been used to target millions of young black men: arrest them, jail them, keep them off the streets and behind bars.

Young black men have been especially hard hit, though marijuana laws across the country have also been used to arrest men and women, too, no matter what their skin color, ethnicity, religion, and political affiliation. Those laws have been used as a cudgel to beat the usual and the unusual suspects, too.

Indeed, ever since the passage of the 1937 Marihuana Tax Act, and the appointment seven years earlier of Harry Anslinger to head the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) and thus to become the first U.S. “Drug Czar,” marijuana laws have been used by federal and state governments to intimidate, cower, shame, persecute, and oppress American citizens for doing nothing more or less than smoke the dried flowers of the cannabis plant.

Fortunately, Cheech and Chong managed to find humor in the absurdities and to make movies like Up in Smoke.

The (FBN) and later the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) which succeeded it, added up to little more than bureaucracies that provided jobs for cops and gave them an excuse to arrest jazz musicians like Louis Armstrong, movie stars like Robert Mitchum, and run-of-the-mill hippies throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and beyond.

The prohibition of marijuana arrived just as the prohibition of alcohol ended.

The prohibition of marijuana arrived just in the nick of time, as the prohibition of alcohol ended and as G-men needed jobs and salaries to battle the “Devil’s Weed.”

For decades, the U.S. Government consistently lied to the American public about the dangers of marijuana. The film Reefer Madness was a small part of a vast propaganda effort that depicted marijuana as a drug that would induce those who used it to commit murder, mayhem, and suicide, and, in the case of black men, to rape white women.

Ever since 1970, the U.S. government has listed marijuana, along with heroin, as a “Schedule I Drug,” which means that it has no medical benefits, though marijuana was part of the U.S. pharmacology until 1937. Moreover, ever since 1996, it has been widely recommended by doctors to patients like Gus Reichbach. Unfortunately, all attempts to remove marijuana from the “Schedule I” category have failed, including the most recent attempt in 2016.

29 states and the District of Columbia allow for some form of medical marijuana.

Still, there has been change for the better. Twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia now allow for some form of medical marijuana. Seven states allow for recreational or “adult use” of marijuana, including Maine, Washington, Oregon, and Colorado.

In all those states marijuana is now a big industry that draws pot tourists and that’s taxed heavily by state governments. Most “red” states, among them Texas, Oklahoma, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Alabama, do not have laws that legalize marijuana.

If Sessions has his way, California, Oregon, Washington, and Colorado will become more like Alabama, where marijuana is concerned. This year Sessions called on Congress to repeal the 2014 Rohrabacher-Farr amendment that prohibits federal funding for police work in states where “the use, distribution, possession and cultivation of medical marijuana” is legal.

Curiously, or perhaps not, Sessions is a states’ righter when it’s convenient for him, and against states rights where marijuana is concerned.

The fact that it’s a multi-billion-dollar-a-year capitalist industry in the U.S. — most of it black market and underground — and that some adults and some teens abuse marijuana, shouldn’t mean that those who use it responsibly, for whatever reason, ought to be criminalized. Unfortunately, criminalization has been the pattern in the United States, where more than 20 million people have been arrested and incarcerated for the possession of marijuana, usually for less than an ounce, over the past several decades.

More than 20 million people have been incarcerated for the possession of marijuana.

Judge Gus Reichbach was eternally optimistic and hopeful, though every administration endorsed the war on marijuana, which is one of the longest-running wars in U.S. history. It was always a war against people, mostly working class. Nixon had a chance to bring about a truce when the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse, chaired by former Pennsylvania Governor Raymond P. Shafer, recommended the decriminalization of marijuana possession in 1972.

Nixon ignored the “Shafer Report” and ramped up the war on drugs. Carter continued Nixon’s policy. That meant spraying Paraquat on marijuana fields in Mexico at a time when most marijuana in the U.S. came from south of the border, a policy that had the unintended consequence of jump-starting the domestic cultivation of marijuana in a vast area in California known as “The Emerald Triangle.” In a curious twist of history, Hmong immigrants who grew opium poppies and worked with the CIA to combat communism in Laos are now proudly cultivating marijuana in California.

The marijuana story is filled with paradoxes, ironies and contradictions.

Ronald Reagan waged war on marijuana with help from his wife Nancy.

In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan waged war on marijuana with help from his wife Nancy, who urged Americans to “Just Say No” — a slogan that became a joke. Reagan’s Attorney General, Ed Meese, called marijuana “the gateway drug,” and while it’s true that some graduate from weed to heroin and cocaine, the true gateway drugs have been the ubiquitous pack of cigarettes and equally ubiquitous six-pack of beer.

Bush I and Bush II were no better than the Reagans.

For a time, it looked like Bill Clinton, who admitted that he smoked, and yet didn’t inhale, would defend the culture of pot, but he wasn’t much better than his predecessors. Obama allowed that he smoked weed as a teenager, and, while he occasionally muzzled the DEA, he disappointed most marijuana activists, including Keith Stroup at the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) who wanted him to issue an executive decree and make it all legal.

Every year, beginning in 1967, Reichbach would say, “next year marijuana will be legalized all over the country.” He kept on repeating that mantra year after year until he died in 2012.

When he came out as a medical cannabis patient, he noted that it was “barbaric” to deny marijuana to those like himself who were suffering.

When some of his friends warned him that he might experience repercussions for his op-ed piece, he said, “It is to help all who have been affected by cancer, and those who will come after me, that I now speak.”

It’s too bad that he’s not around today to tell Jeff Sessions that it’s sheer lunacy to roll back medical marijuana when the nation is in the midst of an obscene opioid epidemic that has destroyed the lives of millions of Americans and cost the economy billions of dollars.

Also see “Maverick Judge Reichbach Offers Verdict on Cuba,” by Jonah Raskin / The Rag Blog /January 19, 2012.

[Rag Blog national contributor Jonah Raskin is also the author of Marijuanaland: Dispatches from an American War, and the co-author of the story for the feature-length pot picture, Homegrown.]

- Read more articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog.