A story for National Poetry Month.

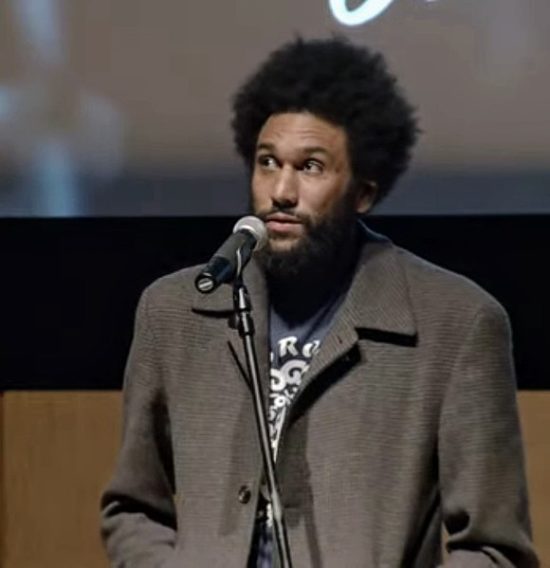

Poet Tongo Eisen-Martin, 2019. Still from YouTube, Wikimedia Commons

SONOMA COUNTY, Calif. — English Department purists might complain that Tongo Eisen-Martin doesn’t write “real” poems, that is poems about birds and flowers, and thus shouldn’t be featured this year during National Poetry Month, which as always falls in April.

Eisen-Martin’s first book, someone’s dead already, was published by Bootstrap Press. His second, Heaven Is All Goodbyes ($11.17) was published by City Lights in its venerable Pocket Poets Series. Tongo’s brother Biko, an artist and an actor, designed the cover.

The first poem in the volume is titled, “Faceless.” The last is titled “The Oldest Then the Youngest,” and begins, “Grandmother, why don’t you ever talk about your children who the first world murdered?” The grandmother replies, “Because, son, I haven’t run out of knife handles.”

True enough, the poems don’t evoke birds and flowers, the end of winter and the coming of spring. But they do what almost all innovative and original poems do: they engage with human consciousness and play with words and images.

He carries on a local tradition that reveres poetry above all other forms of literature.

The current San Francisco poet laureate, Eisen-Martin carries on a local tradition that reveres poetry above all other forms of literature, and that goes back at least as far as the 1860s, when Ina Coolbrith published her own verse. Later, she became California’s first poet laureate.

Eisen-Martin sees San Francisco today as a “dystopia where even the wealthy are incarcerated.” The city’s streets, he explains, once felt like home. Now, they’re a kind of no man’s land.

In the poem, “we may all refuse to die at the same time,” (Eisen-Martin doesn’t capitalize the title) he writes, “They lynched his car too. Strung it up right next to him.” I’d call that gallows humor.

In “I Almost Go Away” (here the poet capitalizes the title) the speaker, who might or might not be Eisen-Martin himself, begins conversationally, with “Sorry I’m late, dear,” gradually builds up steam and confesses, “I am a proletariat-folding-chair class victim.”

Words such as “class victim,” “lynching” and “proletariat” don’t often show up in post-modern poetry. If and when they do, they’re usually in the service of an ideology and with an explicit political agenda. That’s not Eisen-Martin’s game.

But make no mistake about it, his poems are “political.” They circle around the themes of power, powerlessness, and the potential for decolonization and resistance.

The author aims to deconstruct ‘ruling class hegemony.’

That the author aims to deconstruct “ruling class hegemony,” as he calls it, ought not to be surprising to anyone familiar with his own innovative curriculum, “Genocide Again,” which he wrote nearly a decade before the murder of George Floyd and the arrvival of Black Lives Matter.

The “Genocide Again” curriculum invites “teacher-students and student-teachers” to “engage the realities of extra-judical killing of Black people with critical thinking and analysis.” In the Introduction to the 33-page document, which comes with art, photos, and prompts for writing assignments, Eisen-Martin explains that “In 2012, police summarily executed more than 313 Black people — one every 28 hours.” That’s nearly one every day.

The author tells me during a recent phone conversation that he prefers the word “genocide” to the phrase “systematic racism” — which has been used increasingly by corporate media in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death. “Systematic racism,” Eisen-Martin explains, “doesn’t indict the ruling class.”

For him, genocide means “extermination and liquidation.” It includes the “civilizer” who becomes the “exterminator” (think Mr. Kurtz in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness) and it incorporates “those oppressed individuals who are addicted to the status quo.”

There’s an oppressor who “lives in our heads,” Eisen-Martin tells me.

He would like those who read his poetry — or hear him perform it — to ask themselves, “How much hegemony do I facilitate?” and “What deals do I make with the devil?” Also, he would like readers and listeners to see and to recognize that “they aren’t on the sidelines, but rather protagonists who participate in the political process, whether they know it or not.”

Reality isn’t fixed in his poetry.

Not surprisingly, reality isn’t fixed in his poetry, but rather something that’s fluid and that can be altered by the reader and the listener.

An activist as well as as a poet and teacher, Eisen-Martin follows some of the variegated paths carved out by Malcolm X, James Baldwin, Franz Fanon, Paulo Freire, and William Patterson, an African-American and member of the Communist Party USA, who edited the 1951 petition, “We Charge Genocide” that was presented to the United Nations.

That petition states that the “mass slayings on the basis of race call aloud for condemnation.” It calls for “an end to these terrible injustices that constitute a daily and ever-increasing violation of the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.”

(Allen Young wrote about the 1951 “We Charge Genocide” petition for The Rag Blog, July 2, 2020.)

A 20th-century-European Jew named Raphael Lemkin, who experienced Fascism first hand, coined the word “genocide” and then wanted to own it. In 1951, when William Patterson edited “We Charge Genocide,” Lemkin accused him of being an agent of the Soviet Union and insisted that the treatment of Blacks didn’t qualify as “genocide.”

That kind of duplicitous thinking doesn’t surprise Eisen-Martin, who was born and raised in San Francisco and educated at UC Berkeley. He has an M.A. from Columbia University in New York, where he taught at the Institute for Research in African-American Studies. His own education was deepened by his experience as a teacher at San Quentin and Riker’s Island, the jail operated by the New York City Department of Corrections, which houses over 100,000 inmates every year.

‘If it has a prison, it is a prison. Not a city.’

In “Faceless,” he writes, “If it has a prison, it is a prison. Not a city.”

Much of Eisen-Martin’s thinking has been shaped by his mother, Arlene Eisen, a Sixties radical and the author of the groundbreaking book, Women of Vietnam (1974), published by People’s Press of San Francisco and illustrated by artist and muralist, Jane Norling. Though he was born in 1980, just in time for the “Reagan Revolution,” he’s a child of the 1960s.

“In 1968 it looked like a victory of the proletariat was possible,” Eisen-Martin tells me. “The late 1960s are a preoccupation of mine.”

The “Martin” in Eisen-Martin comes from his Black father, who was politicized by Arlene Eisen. The name Martin was “passed down,” the poet tells me, from “the days of slavery.” As for “Tongo,” it derives from the name, Josiah Tongogara, a commander of the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army who died in 1979 in an automobile accident, or so Wikipedia says. Eisen-Martin insists that Tongogara was assassinated.

Almost everywhere he looks, he sees assassination, murder, and genocide.

Eisen-Martin tells me that he doesn’t change his poems when he reads them aloud, though he says he might “soften a line or a phrase so it isn’t too jarring.” He doesn’t want to “trip up the audience,” but to make a poem understandable.

At the end of my conversation with him, Eisen-Martin tells me about a recent conversation he had with Emory Douglas, formerly the Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party and an artist and illustrator for the Panther newspaper. Douglas, now 77, pointed out that Black Lives Matter has so far not led to an organization, political structure. and instruments for social change.

“We went from the high drama over the summer to business as usual,” Eisen-Martin tells me, “What a good job the ruling class has done to keep the masses opiated!”

His poems can act as instruments to shock, deprogram, unthink, and recreate.

[Jonah Raskin, a regular contributor to The Rag Blog, is the author of American Scream: Allen Ginsberg’s ‘Howl’ and the Making of the Beat Generation.]

- Read articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog and listen to Thorne Dreyer’s Rag Radio interviews with Jonah.Say hello now to Heaven Is All Goodbyes, especially for National Poetry Month.