“The underground is not a place but a way of life. You can be underground most anywhere, from the Upper West Side of Manhattan to Hermosa Beach, California.” — Bryan Burrough

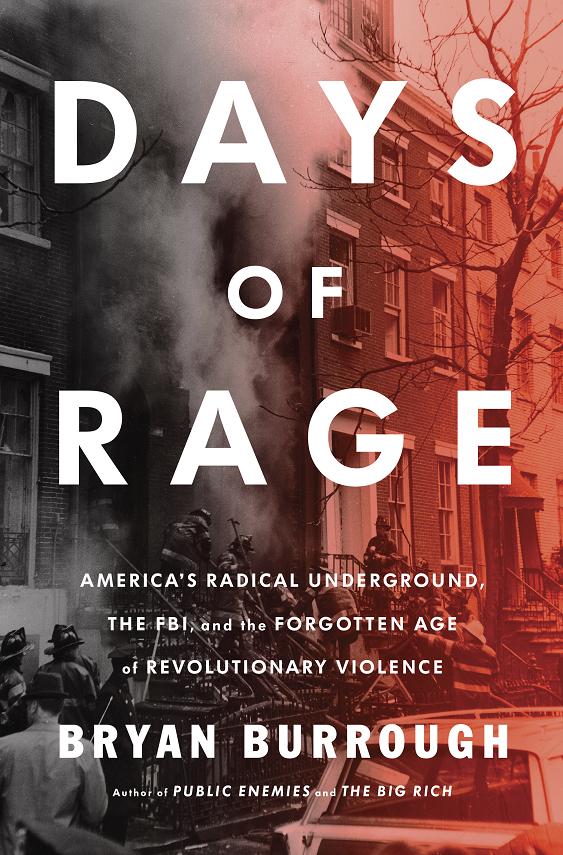

Bryan Burroughs has probably written the book about America’s radical underground at least for our time. Researching Days of Rage: America’s Radical Underground, the FBI and the Forgotten Age of Revolutionary Violence, he talked to dozens and dozens of people, read almost all the literature, and studied the salient documents.

Days of Rage is Burrough’s sixth book. Previous works include Public Enemies (2004) that was made into a gangster film with Johnny Depp as John Dillinger and Christian Bale as FBI agent Melvin Purvis.

For nine years, while based in Dallas, Texas, he worked as a reporter for the Wall Street Journal and followed the money trail.

Born in Temple, Texas, and a part-time resident of Austin, he’s as much of a Texan as Marilyn Buck, whom he writes about in Days of Rage, though there’s very little common ground between them. It’s a big state with a big state of mind.

Burrough writes about the Black Panthers, the Black Liberation Army, the Symbionese Liberation Army, and the New World Liberation Front, but the heart of his book focuses on the Weather Underground.

Vanity Fair is serializing sections of the book. The New York Post carried a sensational story based on information about bombing and bomb makers that Burrough brings to light in Days of Rage.

He has already stirred up a Texas-size dust storm; more stormy weather seems to lie ahead.

Cool, calm, and very collected, Burrough is ready for whatever and whoever comes his way.

Abbie Hoffman, who coined the phrase, “Days of Rage,” might look for him and complain were he still alive, but Abbie never registered the phrase with the copyright office. After all these years, he’d have no legitimate beef with Burrough.

Others still alive and kicking will no doubt find much to beef about in Days of Rage. Let the beefing begin.

Jonah Raskin: You were born in 1961. So, you were eight in 1969. Do you have any memories of that era?

Bryan Burrough: I do not. I didn’t hear of the Weather Underground until I was an adult. I do remember hearing about Patty Hearst when I was 13.

Where were you when you were a boy?

Rural Texas. I grew up in Temple, lived there from age eight to 18. I go back regularly because my parents still live there. I spend a lot of time these days in Austin. My girlfriend is there. It’s my favorite place to be. I have an office in Austin.

In some ways you seem like a near perfect person to write about the underground. You don’t have an ideology and didn’t belong to a radical group or organization.

People appreciated the fact that I had no baggage. Others didn’t want to talk to me because I didn’t share their politics.

How do you define your own politics?

I’m apolitical. If you look back at the books I have written they’re not on political topics. I told people I had no political agenda and that I wanted to write accurate history. Some reviews from the left call me “a latent fascist.”

You end the book with Sekou Odina, a former Black Panther and member of the Black Liberation Army, who says that all empires are doomed and that the American empire is also doomed. Why end with him?

I wanted to end with that type of voice. Sekou was active politically for 40-plus years, 30-plus years in prison. I am not drawing lessons in this book. Let the participants draw their own conclusions.

The Weather Underground would not be able to operate today if they were to use the technology they used in the 1970s.

Correct. They would not have lasted. No way. We know that we’re under surveillance today, all the time. They would have been arrested from the get-go.

You talked to people who had never previously talked about their underground activity and yet they talked to you.

Robbie Roth was one of them. Emotionally and mentally he’s tough. He was disciplined in what he said, and while he admitted that he was a part of the Weather leadership he wouldn’t describe his own underground activities. I walked away from our meeting with a lot of admiration for him.

You wrote this book without talking to key Weather people — Bernardine Dohrn, Bill Ayers, Jeff Jones, and Eleanor Stein.

I must have tried 20 times to talk to them. At this point Bill is comfortable telling his own story. He doesn’t need to talk to me. Some people don’t remember. I can’t fault them for wanting to protect themselves. I do feel angry when people lie, when they say that Weather never aimed to take a single human life. They did in the early stage.

Do you think some of your sources talked because they wanted revenge on former friends and comrades?

That occurred to me while doing research for the book. I had a section about ulterior motives. I wondered why Weather people were angry and why lesbians were some of the last people underground. It was all speculation and I took it out. Many of the people I spoke to are now in their 70s; they’re grandparents. Some are deeply troubled about what they did and they’re trying to come to terms with their legacy.

Why do you think that Ron Fliegelman talked to you about his role making bombs?

I get asked that a lot. I found among some ex-Weather people resentments toward Bill and Bernardine. People like Ron Fliegelman and Silvia Baraldini, who now lives in Italy, were written out of history. People talked simply because I knocked on their doors and showed that I wanted to listen to their stories, which usually aren’t the ones that are told from the podium.

Some Weather people lived privileged lives underground while others knew poverty. That created some lasting resentments.

The title of your book uses the phrases “radical underground” and “revolutionary violence.” You don’t use the word terrorist and terrorism there.

Terrorist and terrorism suggest indiscriminate violence. Most Weather violence was not indiscriminate. I think of what they did as “protest bombing.” It was by and large not designed to kill.

Someone recently suggested to me — a former SDS member who aided the Weather Underground — that someone in leadership ought to be charged with the deaths of Terry Robbins, Teddy Gold, and Diana Oughton in the townhouse explosion in March 1970 in Manhattan.

In March 1970 there was no top down leadership. Terry Robbins ran the show in New York and while Bill and Bernardine knew what he was doing, they were not supervising him and he was not under their thumb.

I’ve heard writers for Mother Jones magazine say that the FBI knew where the Weather fugitives were hiding and that they felt they were more useful underground than in prison.

That sounds like a left-wing conspiracy theory. In the 1970s the FBI was not that smart and not that competent. Fact is the fugitives couldn’t be found. It’s helpful, too, to remember that the underground is not a place but a way of life. You can be underground most anywhere, from the Upper West Side of Manhattan to Hermosa Beach, California.

You attended Marilyn Buck’s memorial service in Harlem in 2010 and you write about it in the epilogue to your book. You say “the audience was a Who’s Who of the old underground movement.” How did it feel to be there?

I got invited. I went with a group of people. I was introduced; no one really knew who I was. Listening to the speakers I felt I was in a parallel, unreal universe. Marilyn Buck had admirable qualities — she could be kind and compassionate. She also committed crimes to further her political aims. I would have liked a more balanced perspective. I didn’t feel comfortable with the way that she was elevated to sainthood. Some people are still out there, still living in the mindset of the underground

You tell the curious story of Jennifer Dohrn’s underwear.

FBI agents broke into her apartment, stole her panties, and presented them to an agent named John Kearny when he retired.

There are moments of humor and irony, too, in your new book. Radicals who thought that they were public enemies and who believed that they very much wanted by the police learned that they weren’t really wanted after all.

When Weather Underground fugitives, Robbie Roth and Phoebe Hirsch, showed up in Chicago to surrender to authorities for what they had done during the Days of Rage in October 1969 the officer on duty told them to come back the next day.

- Read more articles by Jonah Raskin on The Rag Blog.

- Find Rag Blog articles by and about Bill Ayers, Bernardine Dohrn, and Marilyn Buck, and listen to Thorne Dreyer’s Rag Radio interviews with Ayers, Dohrn, and Jonah Raskin.

[Rag Blog contributing editor Jonah Raskin is the author of For the Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman and the editor of The Weather Eye: Communiques from the Weather Underground, May 1970 —May 1974.]

Wow Jonah — what was the point of the interview. This is almost as unStudslike as Burrough’s book. Why didn’t you ask him to talk about anything????