Does Obama understand his biggest foreign-policy challenge?

By Juan Cole / December 12, 2008

The president-elect wants to work with the Pakistani government to “stamp out” terror. It’s not nearly that simple.

A consensus is emerging among intelligence analysts and pundits that Pakistan may be President-elect Barack Obama’s greatest policy challenge. A base for terrorist groups, the country has a fragile new civilian government and a long history of military coups. The dramatic attack on Mumbai by members of the Pakistan-based Lashkar-e Tayiba, the continued Taliban insurgency on the Pakistan-Afghanistan border, the frailty of the new civilian government, and the country’s status as a nuclear-armed state have all put Islamabad on the incoming administration’s front burner.

But does Obama understand what he’s getting into? In his “Meet the Press” interview with Tom Brokaw on Sunday, Obama said, “We need a strategic partnership with all the parties in the region — Pakistan and India and the Afghan government — to stamp out the kind of militant, violent, terrorist extremists that have set up base camps and that are operating in ways that threaten the security of everybody in the international community.” Obama’s scenario assumes that the Pakistani government is a single, undifferentiated thing, and that all parts of the government would be willing to “stamp out” terrorists. Both of those assumptions are incorrect.

Pakistan’s government has a profound internal division between the military and the civilian, which have alternated in power since the country was born from the partition of British India in 1947. It is this military insubordination that creates most of the country’s serious political problems. Washington worries too much about other things in Pakistan and too little about the sheer power of the military. United States analysts often express fears about an internal fundamentalist challenge to the chiefs of staff. The main issue, however, is not that Pakistan’s military is too weak, but that it is too strong. And that is complicated by the fact that elements within the military are at odds, not just with the civilian government, but also with each other.

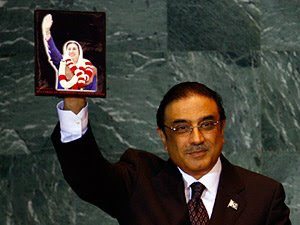

Gen. Pervez Musharraf ruled the country with an iron fist from the fall of 1999 (when he staged his coup against an elected prime minister) until he resigned under threat of impeachment in August of this year. His civilian rival, Asaf Ali Zardari, was elected president in September. Zardari had become the de facto head of the left-of-center Pakistan People’s Party after his wife, Benazir Bhutto, was assassinated while campaigning for Parliament in late December 2007. In the parliamentary elections of February 2008, which were relatively free and fair, the PPP emerged as the largest party in Parliament.

Zardari and his prime minister, Yousuf Raza Gilani, have vowed to crack down on terrorism. Zardari is said to be committed to vengeance against the Pakistani Taliban, since he blames them for his wife’s assassination. The possibility that a Western-educated woman liberal might again become Pakistan’s prime minister had been unbearable for the fundamentalist Taliban. Since Zardari became president, the Pakistani military has vigorously pursued a massive campaign against the Taliban in the tribal agency of Bajaur. The fierce fighting is said to have displaced some 300,000 persons. Of these operations against the Pakistani Taliban, Obama said on “Meet the Press” that “thus far, President Zardari has sent the right signals. He’s indicated that he recognizes this is not just a threat to the United States but is a threat to Pakistan as well.”

Likewise, after the attack on the Indian financial and cultural center of Mumbai on Nov. 26-29 of this year, Zardari argued that Pakistan as well as India has been targeted by terrorism, and that it is a legacy of the ways in which the U.S. used radical Islam to fight the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Zardari wrote: “The Mumbai attacks were directed not only at India but also at Pakistan’s new democratic government and the peace process with India that we have initiated. Supporters of authoritarianism in Pakistan and non-state actors with a vested interest in perpetuating conflict do not want change in Pakistan to take root.”

But Zardari will find it difficult to get control of the entire Pakistani government and the various “non-state actors” it has spawned to pursue Pakistani military interests in Afghanistan and Kashmir. Among his biggest challenges will be to gain the loyalty not only of the regular military but also of those officers detailed to the Directorate of Inter-Services Intelligence, an organization of some 25,000 that was founded in 1948 to promote information-sharing among the army, navy and air force. In the 1960s, military dictator Ayoub Khan used the ISI to spy on domestic rivals, and over time it developed a unit focusing on manipulating civilian politics. Zardari tried to abolish that political unit in late November.

During periods of military dictatorship, the ISI has tended to be given a much-expanded role, both domestically and abroad. During the 1980s, Gen. Zia ul-Haq created an Afghanistan bureau in the ISI, through which the Reagan administration funneled billions to the mujahedin to fight the Soviet occupation. In the late 1980s, dictator Zia initiated an ISI-led covert operation, Operation Tupac, aimed at detaching the disputed Muslim-majority state of Kashmir from India.

Kashmir had been a princely state in British India, ruled by a Hindu raja who took it into Hindu-majority India during partition. The Pakistanis fought an inconclusive war but failed to annex it to Pakistan, and the United Nations called for a referendum to allow the Kashmiris to decide their fate. India, which viewed Jammu and Kashmir as an Indian state, never allowed such a plebiscite to be held. Obama has suggested that he might send former President Bill Clinton as a special envoy in a bid to resolve the Kashmir dispute once and for all.

From a Pakistani nationalist point of view, Indian rule over Kashmir differed only in longevity from the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, and both involved the illegitimate occupation of a Muslim people by an infidel government. The ISI helped create six major guerrilla groups to operate against India in Kashmir, including the Lashkar-e Tayiba (Army of the Good), a paramilitary arm of the Center for Missionizing and Guidance (Da’wa wa Irshad) of former Islamic studies professor and mujahed in Afghanistan, Mohammad Hafiz Saeed.

From 1994, the ISI backed the Taliban in the quest to take over Afghanistan from the warlords who came to power after the fall of Soviet-installed Muhammad Najibullah in the early 1990s. Elements in the ISI favored a hard-line form of fundamentalist Islam and so were pleased to support the Taliban on ideological grounds. Others were simply being pragmatic, since the Taliban, from the Pushtun ethnic group, had been refugees who attended seminary or madrasah in Pakistan. They were pro-Pakistan, while many of the warlords had become clients of India, Iran or, ironically, Russia.

In 2001, immediately after the 9/11 attacks, the Bush administration gave Pakistani military dictator Pervez Musharraf an ultimatum. He had championed the Taliban policy despite being a secularist himself, but was forced to turn against his former allies, who were then overthrown by the U.S.-backed warlords of the Northern Alliance.

Elements in the ISI and the military, however, continued to back the Taliban. They were deeply dismayed that the Karzai government in Kabul was independent of Islamabad and had strong ties to India. Under U.S. and Indian pressure, in 2004 the Musharraf government blocked the Pakistan-based guerrilla groups from further attacking Indian Kashmir from Pakistan, causing many of their members to go fight instead alongside the resurgent Taliban in northwestern Pakistan and southern Afghanistan. In response to the need to distance themselves from the terrorist groups, the Pakistani government and the ISI are alleged to have created cells made up of former officers who covertly give training, arms and other support to the Taliban and to the organizations fighting India in Kashmir.

To some extent, then, Pakistan’s powerful national-security apparatus has been divided against itself for much of the past decade. The contradictory agendas of various parts of the Pakistani government and of its shadowy networks of retired or ex-officers have created policy chaos. Even while the army is engaged in intense fighting against the Pakistani Taliban of Bajaur, it appears to be backing other Taliban groups that have struck at targets inside Afghanistan from south Waziristan, another tribal agency on the border of the two countries. Last June, when U.S. forces engaged in hot pursuit of these Taliban staging cross-border raids, they came under fire from Pakistani troops who sided with the Taliban.

The complex layers of the ISI, a state within the state, make it questionable whether Musharraf ever really controlled it. Now Pakistan’s new civilian president is even less well-placed to control it, or to discover how the militant cells work, both inside the ISI and among the retirees. It is not even clear whether the ISI is willing to take orders from Zardari and other officials in the new government. When Prime Minister Gilani announced that the ISI would have to report to the civilian Interior Ministry, the decree was overturned within a day under “immense pressure from defense circles.” When the government pledged to send the head of the ISI to India for consultations on the Mumbai attacks in late November, it was apparently overruled by the military.

The captured terrorist in Mumbai, Amir Ajmal Qassab, appears to have told Indian interrogators that his group was trained in Pakistani Kashmir by retired Pakistani officers. It is certain that President Zardari, Prime Minister Gilani, and Army Chief of Staff Ashfaq Kiyani were uninvolved in the terrorist strike on Mumbai. But were there rogue cells inside the ISI or the army officer corps that were running the retirees who put the Lashkar-e Tayiba up to striking India? On Sunday, Zardari’s forces raided the Lashkar-e Tayiba camps in Pakistani Kashmir and arrested a major LeT leader, Zaki-ur-Rehman Lakhvi, whom Indian intelligence accused of masterminding the Mumbai attacks. The move was considered gutsy in Pakistan, where there is substantial popular support for the struggle to free Muslim Kashmir of India, a struggle in which the Lashkar has long been the leading organization.

This murky Chinese puzzle raises the question of how Obama can hope to cooperate with the Pakistani government to curb the groups mounting attacks in Afghanistan and Kashmir. The government itself is divided on such policies, and there appear to be cells both within the state and outside it that have their own, militant foreign policy. The United States, going back to the Cold War, has long viewed the Pakistani army as a geopolitical ally, and Washington tends to prefer that the military be in power. Since Gen. Musharraf was forced out, U.S. intelligence circles have been lamenting the country’s “instability,” as though it were less unstable under an unpopular dictatorship. If Pakistan — and Pakistani-American relations — are to have a chance, it will lie in the incoming Obama administration doing everything it can to strengthen the civilian political establishment and ensure that the military remains permanently in its barracks. The military needs to be excluded from political power, and it needs to learn to take orders from a civilian president. At the same time, Obama should follow through on his commitment to commit serious diplomatic resources to helping resolve the long-festering Kashmir issue.

Source / Salon