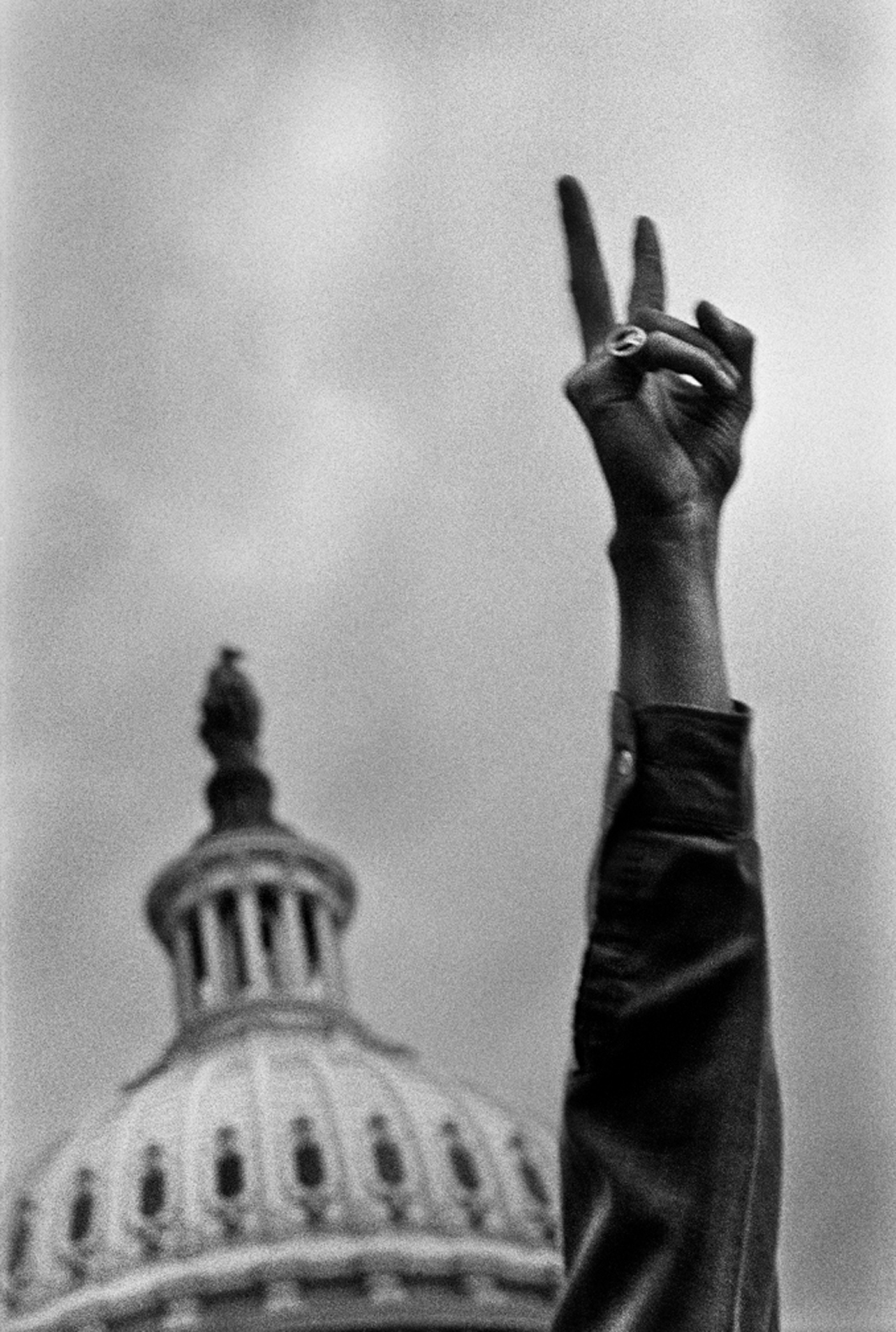

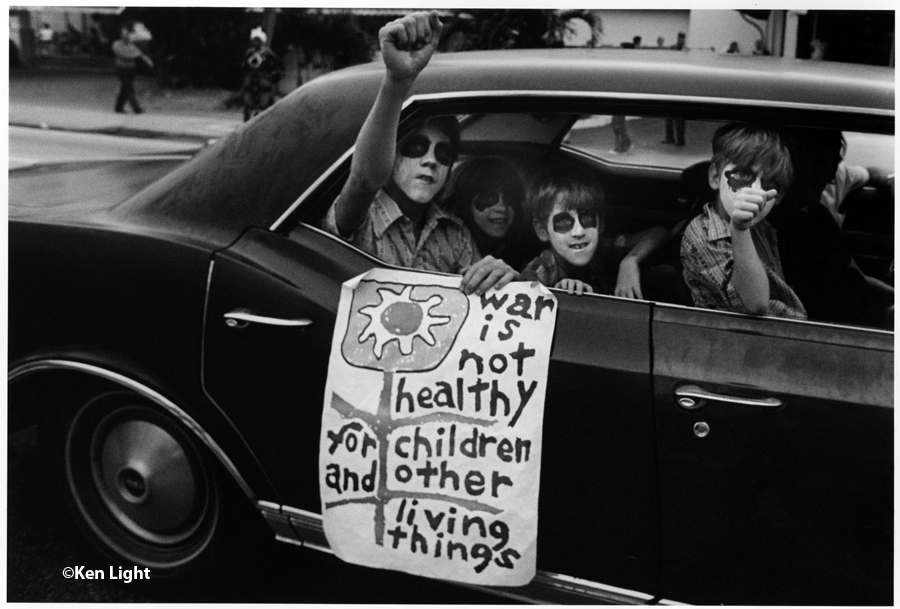

In ‘What’s Going On? 1969-1974,’ Light captures the marches, the rallies, the protests, the guerrilla theatre performances, and the police riots.

Ken Light disscussed his experiences as a social documentary photographer and his new book, What’s Going On? 1969-1974 — as well as his work photographing on Texas’ Death Row — with Thorne Dreyer on Rag Radio, Friday, Jan. 22, 2016, 2-3 p.m. (CT), on KOOP 91.7-FM in Austin. Listen to the podcast of this show.

Ken Light disscussed his experiences as a social documentary photographer and his new book, What’s Going On? 1969-1974 — as well as his work photographing on Texas’ Death Row — with Thorne Dreyer on Rag Radio, Friday, Jan. 22, 2016, 2-3 p.m. (CT), on KOOP 91.7-FM in Austin. Listen to the podcast of this show.

I was called a sixties’ burnout one time. An actual sixties’ burnout was the name-caller so I didn’t take it personally. And, after all, it was the late seventies-early eighties and I still had long hair and a beard, no respectable career prospects, and a hyperactive thumb that took me cross-country and back on the strength of a whim and a clever slogan hand-scrawled on a shopping bag (“Whichever way the wind blows”; “Home to do laundry”; “I am unarmed”; “I’ve got the matches”).

So, yes, I did hang on to the stereotypical character traits longer than most of my peers, who, by the time I traded in my thumb for a used Pontiac Sports Suburban with a leak in the transmission fluid pan, had steady jobs with fancy titles and growing families.

I had an excuse: I loved the sixties.

I had an excuse: I loved the sixties. I loved living them then and I love reading and writing and speaking about them now. Don’t let anyone fill your head with “Yes, but”s. For all of its flaws, it was a remarkable period. The pros far outweighed the cons and the positive effects are still being felt today. I especially love memoirs written by veterans of the period, but I have never reviewed a book of photographs from the period that were taken by one of the master photojournalists.

So it was my pleasure to read Ken Light’s What’s Going On? 1969-1974. [Disclosure: My name is Ken, too.]

The first two sides, 1969-1974

Ken was a card-carrying photographer with Liberation News Service, or LNS, the AP-UPI of the underground press. Members of the LNS collective sent out three packets of news articles a week to underground papers that subscribed to it.

These articles came in to LNS from journalists and activists all over the world. First-hand accounts from the political hotspots. Participant analyses. The stories the mainstream press wouldn’t touch. The smallest underground paper in the world could reprint any of them simply by subscribing to LNS.

The articles were laid out in two-column, ragged-edge format, because that’s how many of the underground papers were laid out in those days. If you liked an article, you could simply cut it out of the news packet and paste it down on your layout sheet without having to retype it. If an article was three column inches too long to fit the available space, you could cut out a three-column inch paragraph from anywhere you wanted in the article, then connect the two adjacent paragraphs with glue stick or rubber cement.

A dozen or more photographs and cartoons appeared in the second part of the packet. Some of them complemented articles in that same packet; others told their own stories. Ken was one of those photographers.

I was excited just taking ‘What’s Going On?’ out of the box that delivered it to me.

So I was excited just taking What’s Going On? out of the box that delivered it to me. I was expecting it to be a political book with photos and literature from the antiwar movement and I wasn’t disappointed. The two-page inside cover spread is a collage of three memoranda from his FBI files that connect him nonviolently with the underground press, Liberation News Service, and antiwar actions in the Ohio cities of Columbus, Kent, Athens, and Cleveland:

It is noted that the activities of LIGHT appear to be confined to the anti-war, anti-draft and anti-establishment areas, and no information has been developed which indicates membership in a subversive organization or a propensity for violence.

A page on the back inside cover spread, with the subject “YIPPIE COMMUNE at 718 STOW, KENT, OHIO,” is almost totally blackened out.

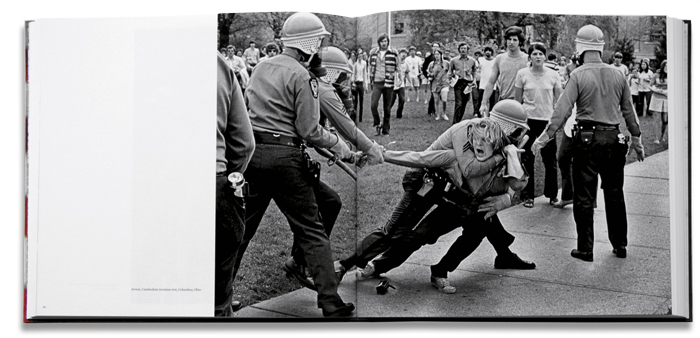

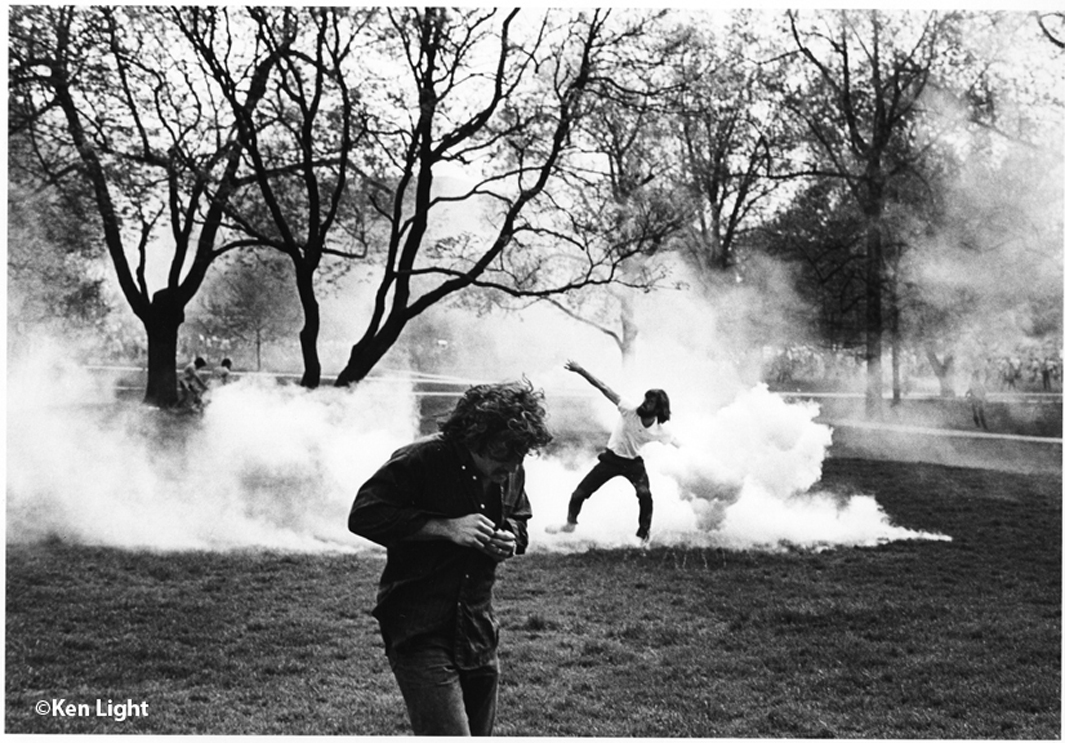

What’s Going On? is Ken Light’s photographic autobiography from the years 1969 through 1974. His photos capture the marches, the rallies, the protests, the guerrilla theatre performances, and the police riots, both nationwide and local:

- May Day demonstration in Washington, D.C., in 1971, when over 12,000 demonstrators were arrested while trying to shut down the city, the largest mass arrest ever in our country’s history;

- a riot in Columbus after Nixon invaded Cambodia in April 1970, only weeks before four students would be murdered at Kent State University on May 4;

- the Free John Sinclair Rally in Ann Arbor in 1971 with Bobby Seale and Jerry Rubin among the speakers and John and Yoko among the performers;

- the Vietnam moratorium in D.C. in 1969;

- a veterans’ rally in St. Louis;

- a clean-cut young three-piece band at a rally in southeast Ohio, with sign in front of the stage promising George McGovern if you really want change on the top and offering a free ham to anyone who signs up out front on the bottom.

- a Women Strike for Equality march in New York City in 1970;

- the Buffalo Creek mine disaster in West Virginia, 1972, that left 125 dead, 1,101 injured, and over 4,000 people homeless;

- on the streets of Miami Beach, 1972, where antiwar activists spent the summer befriending the local community of Jewish senior citizens and exposing the supposedly militant right-wing Cubans as paper tigers so that we could demonstrate outside the nominating conventions of both major parties;

- and many more.

At the same time, as a credentialed photographer with LNS, he is able to capture “the other side”: the pro-war, anti-counterculture Nixon supporters selling campaign hats in a Nixon rally in Columbus; in a veterans’ home; inside the Republican National Convention in Miami Beach, summer 1972; Nixon’s inauguration the following January.

I saw it also as a war between the Life Culture and the Death Culture.

I remember the period as being a supposed war between the generations with the age of 30 being the formal credibility dividing line. I saw it also as a war between the Life Culture and the Death Culture — with the latter’s capital city being Washington, D[eath] C[ulture].

I never gave extended thought to the idea of the period’s being a civil war within our own generation, even though intellectually I understood (think Tricia Nixon, Dan Quayle, Dick Cheney), until Ken’s photostory reminded me of the many young people our age who cheered and danced and wore Nixon hats at Republican rallies. Are you still surprised to discover on Facebook that an old high school friend has gone tea party?

The third side

But there was more to the sixties than the antiwar forces versus the establishment, a third side. Some people missed the action altogether. Ken gives representation to the vast community of Americans who were politically inactive, whether because they were too young or too old or just too disconnected to get involved; who were involved in ways that many of us could not imagine; or who the mainstream media just missed.

He captures these folks at work and at leisure, doing what they had to do to get by, perhaps knowing that a Movement was happening around them, perhaps not — students in New York schools; shoe factory workers in Nelsonville, Ohio; migrants in Salinas, California, in 1972; sunbathers lying on the sand at Jones Beach, on New York’s Long Island; elderly cafeteria workers on strike in Athens, Ohio; a hippie looking out the back window of a van.

Ken expands your vision of the sixties

beyond the stereotypes.

Ken captures all of them and in that way he expands your vision of the sixties beyond the stereotypes. I’m sure that was his intention.

“It was my life, not an assignment”

Photos are arranged at times in what seems to be a random fashion and at other times by category. When the photos are arranged randomly you are reminded of earlier photos and may be inspired to go back and check them out more carefully. Didn’t I just see a high school student? Was that the same Ann Arbor rally? Did he go to Europe more than once?

When the photos are arranged by topic, on the other hand, they capture a unique story in concentrated form allowing for immediate comparison and contrast. The sequence of photos taken at the Women Strike for Equality march in New York City in 1970 shows women marching proudly, carrying political street signs, and raising clenched fists, while a fourth photo shows spectators gazing with curiosity and bemusement.

Another series depicts returning prisoners of war and family members at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio in February 1973 as part of Operation Homecoming: a freckle-faced boy with a big grin holding a small flag to the camera; military personnel and civilians looking out at a cloudy sky; a crowd scene from behind, one woman looking apprehensively to the left; a family wrapped in embrace with a returning POW, another family member approaching in joyous tears. You feel like you were there.

A third series includes three photos, each with a different type of vehicle, each evoking a different sensation: seven hippies and a dog in Ann Arbor standing next to a VW van; a young guitarist at the Appalachian folk festival in Kentucky sitting and strumming in the open trunk of a sedan; a shiny Cadillac at a Yosemite National Park campsite, front and center.

I’ll bet those hippies were in Ann Arbor to attend the Free John Rally.

There are themes that appear both at

random and in sequence.

Then there are themes that appear both at random and in sequence. A series of photos from the presidential conventions, Miami Beach 1972, begins on page 9 with a group of retirees from Miami Beach, followed after 30-plus pages with a photo of Hubert Humphrey wearing a Hubert Humphrey campaign pin, then a female protester. Twenty-five pages later a sequence of 10 photos depicts life both inside the convention and on the streets. Toward the end of the book, a group of old probably Jewish women play cards at an old folks’ home in Miami Beach.

Equally as striking as the contrast within single themes is the contrast between adjoining themes. Six photos of President Nixon’s inauguration in Washington, D.C., on January 20, 1973, include one of a young Boy Scout in the middle of a Nixon rally wearing a Nixon badge on his uniform and smiling at the camera, followed by five that take place inside the inaugural ball: young people dancing; Nixon raising four fingers and supporters doing the same. This sequence is followed by a black man sitting on a chair, right leg crossed over left, in a vacant lot in St. Louis, next to a tire in front of a Pepsi-Cola sign printed on the wall behind him.

I think Ken’s point was to avoid categorizing by specific time and place and instead to present the photos as a collage that captures the time and spirit free of event-based restrictions. Here’s what Ken says:

I tried to mix the images to create a sense of what I saw, and in many cases I stay true to the time line, but as you noted, sometimes it’s random. The period in which I worked, 1969-1974, set the frame, and I felt that to create a strong visual story photos could be sequenced to create a visual flow that allows the viewer to get a sense how the movement grew and exploded and then marched to Nixon’s re-election and saw the War end and then we watched as he resigned.

I was 18 when I started so I didn’t have the experience or any idea that I would ever do a book, or even end up as a professor at Berkeley. I couldn’t even see the timeline that was unfolding. It was my life, not an assignment, so I missed many opportunities because I had no money, had to hitch, was organizing, and often put my camera down, was in school, and had to go to classes every once in a while. So 45 years later trying to sequence was a challenge — but I am happy how it flows and it’s all within that period and all connected.

Sure to spur conversations within generations

If any of the photos used the flash I missed them. All appeared to be done with ambient light. All are black and white. The photographer knows how to expose and develop; print quality is excellent. Good use of lighting gives one photo, of a young boy standing on a front porch posing for the camera, almost a 3-D effect.

Watching the rioting protester throw a tear gas canister back at the police while it is still burning, in Columbus, Ohio, following Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia, reminds you that Ken wasn’t afraid to place himself in harm’s way to get the picture.

The Boy Scout at the Nixon rally, front and center in sharp focus, other attendees in background, blurred, shows Ken’s skill in using selective focus.

Ken’s essay, ‘What’s Going On?,’ gives the photos their historical perspective.

Following the photographs, Ken’s essay, “What’s Going On?,” gives the photos their historical perspective and provides dates for some as he travels from his home town in Long Island, New York, to Athens, Ohio, to attend Ohio University, and then across the country and to Europe.

As someone who joined the Movement at the same time as Ken, and in fact grew up in a Jewish suburb on the northeast side of Cleveland, I related almost exactly to his background and later participated in some of the same events: May Day in 1971, Free John Rally in Ann Arbor in 1971, Miami Beach in 1972. I could say a lot more about the events; the photos in Ken Light’s What’s Going On? 1969-1974 spurred my conversation. They are sure to spur many informed and enlightening conversations, not only between generations but within generations.

What’s Going On? 1969-1974 is available online at squareup.com/market/kenlight-photo

Find articles by and about Ken Wachsberger on The Rag Blog .

[Ken Wachsberger is a long-time writer, editor, political activist, and member of the National Writers Union. He is the editor of the four-volume Voices from the Underground Series and a driving force behind Reveal Digital’s underground press digital project.]. He thanks his brother Bob for his thoughts.]

with apologies to all who love the original—-

Those days were called the sixties times:

You that outlived those days, and came safe home,

Will stand a tip-toe when these days are named,

And rouse up at the old calls to action.

You that shall live this day, and see old age,

Will yearly on our vigil feast your neighbours,

And say ‘To-morrow we remember the sixties:’

Then will we will strip our sleeves and show the scars.

And say ‘These wounds I had in those good days.’

Old ones forget: yet all shall be forgot,

But they’ll remember with advantages

What feats we did those days.

And The First of May shall ne’er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remember’d;

We few, we happy few, we band of comrades;

For you those days that stood strong with me

Shall be my comrade; be you now so moderate,

And people now a- sofa

Shall think themselves accursed they were not here,

And hold their personhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon those sixties days.

with apologies to all who love the original—-

Those days were called the sixties times:

You that outlived those days, and came safe home,

Will stand a tip-toe when these days are named,

And rouse up at the old calls to action.

You that shall live this day, and see old age,

Will yearly on our vigil feast your neighbours,

And say ‘To-morrow we remember the sixties:’

Then will we will strip our sleeves and show the scars.

And say ‘These wounds I had in those good days.’

Old ones forget: yet all shall be forgot,

But they’ll remember with advantages

What feats we did those days.

And The First of May shall ne’er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remember’d;

We few, we happy few, we band of comrades;

For you those days that stood strong with me

Shall be my comrade; be you now so moderate,

And people now a- sofa

Shall think themselves accursed they were not here,

And hold their personhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon those sixties days.

Reply