Remembering a Red From Reds

By Jeff Kisseloff / March 5, 2009

The other day I sat in front of my TV watching Warren Beatty’s Reds with tears in my eyes–not because I was so moved by the story of John Reed (although I was), but because I got to see my friend Hugo Gellert for the first time since the day before his death in 1985.

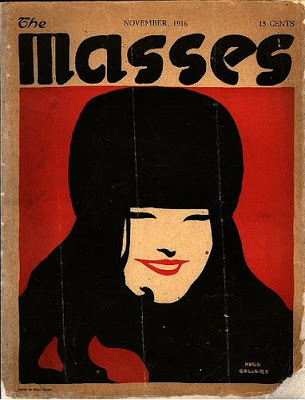

Hugo is pretty much forgotten now, but from 1917 through the 1950s, his illustrations appeared in nearly every progressive and radical magazine in the country, including The Nation. When I got to know him toward the end of his life, he was living in a small house in Freehold, New Jersey, with his wife Livia, who, sadly was as senile as she was bright-eyed. Still, he was always gracious and fun, except when the conversation rolled around to Max Eastman or Whittaker Chambers, two turncoats an unrepentant old leftist couldn’t abide.

I met Hugo in connection with a book I was writing, but long after the interviewing process was over, I’d drive down to Freehold once a month or so to shovel the walk or pick up groceries or do the dishes that were always piled up in the sink. It was a small to price to pay for the privilege of hearing stories from someone who was the living embodiment of the twentieth-century American left. We generally sat by a fire in the living room, which was lined with bookshelves. Livia had arranged the books by size so that they made mesmerizing waves up and down the walls. His studio was upstairs, but whenever I asked for a tour, he always gently demurred.

Hugo didn’t have a lot of heroes, but one of the few was John Reed, whom he knew well as a fellow Greenwich Village bohemian in the years around World War I. Beatty captures that brief epoch of artistic and political rebellion beautifully in Reds, in large part because of his use of “witnesses,” actual acquaintances of Reed and Louise Bryant who pop up as a kind of Greek chorus throughout the film. Hugo was one of them, along with Will Durant, Henry Miller, George Seldes, among others, all of whom are now gone. The film relives the exciting heyday of great foreign correspondents, and Reed may have been the greatest of all with his reporting on Pancho Villa, World War I, and, of course, the Russian revolution, the source of his great masterpiece, Ten Days That Shook the World. He was also an unabashed leftist who played a central role in the formation of the American Communist Party soon after some 16 million people had died for “profits,” as Reed says in the movie. Think what you want about journalistic objectivity, but Reed and others knew the system wasn’t working, and he never thought that being a reporter disqualified him from doing something about it.

Hugo had a brother who was a conscientious objector during the war. He was sent to military prison where he died of a gunshot wound. The Army said it was suicide, but they couldn’t explain how a person could kill himself with a rifle. What Hugo remembered was that soon after his brother’s death Reed returned home from Russia. They bumped into each other on the street. Hugo asked him about the revolution, but Reed only wanted to talk about Hugo’s brother. There’s a scene in Reds where Beatty berates a member of the Socialist Party who missed a meeting because his wife had taken sick. Hugo liked Beatty, but in that scene anyway, that wasn’t the John Reed he remembered.

When I knew Hugo, I think he just wanted to live long enough to take care of Livia until her death. It didn’t work out that way. I saw him one day in December 1985, and toward the end of the afternoon I found him sitting in the kitchen with his head in his hands. I asked him if he wanted to go to the doctor, but he said no. The next day I called the house to see how he was feeling. Surprisingly, Livia answered the phone. She was hysterical. She said Hugo was taken to the hospital and they had refused to tell her whether he was okay. I calmed her down and told her I would call. I did, and a nurse told me that they had spoken to Livia about a dozen times. She said they explained to her as gently as they could each time that he had died. I hung up the phone and cried like a baby.

A couple of days later I drove down to Freehold to find the house crawling with people, most of whom were strangers to Livia. Several of them were helping themselves to Hugo’s work. I managed to shoo them out of the house and then, crossing over the bloodstained carpet where Hugo had fallen and died, I climbed the stairs to see his studio for the first time. One look around, and I realized why he never let me up there. It was an utter mess. Hugo was such a dignified presence, but at 92 years old, he had lost control of the space. Socks and underwear littered the floor alongside drawings–beautiful drawings–that must have been fifty or sixty years old.

Hugo had told me a great story of his contribution to the opening show of the Museum of Modern Art in 1932. He had read an article about a journalist named Vanderbilt who had gotten a jailhouse interview with Al Capone. The Chicago gangster took note of his visitor’s last name, and with his outsized ego, decided he and the robber barons shared a common criminal bond. “Us fellas gotta stick together,” he suggested.

Hugo ran with it, painting a large canvas, depicting Capone manning a machine gun with J. D. Rockefeller, J. P. Morgan, Henry Ford and Herbert Hoover, standing by his shoulder. A young Nelson Rockefeller, who was then in charge of the new museum, took one look and ordered it moved upstairs by the bathroom.

It had never occurred to me that it would be up there in Hugo’s studio, but there the painting was, facing backward leaning against the wall. A few days later Hugo’s brother and I carried it out to the backyard to photograph it. A gust of wind promptly blew the painting against the arm of a lawn chair and punched a huge hole in it. Fortunately, a talented restorer repaired the damage, and the painting in all its restored glory can be seen at the Wolfsonian Museum in Miami Beach. The sale of the painting and the rest of Hugo’s work allowed Livia to live out the rest of her life in comfort.

Now, thanks to the glory of Blu-Ray, there Hugo was again, looking just as I remember him, telling stories in his living room. I can’t recommend the film enough, if not for seeing Beatty and Diane Keaton, but for the privilege of seeing the last remnants of the early twentieth-century left (and a few from the right), still full of piss and vinegar.

One more quick story. Those who were a bit chagrined at the way Beatty intercut some of the most moving scenes of the film–the storming of the Winter Palace to a Russian chorus singing “The Internationale”–with shots of himself and Diane Keaton making love in their flat, might appreciate this. Around the time Reds was released, I was working for Alger Hiss as his legal researcher. One day Alger went down to Soho for lunch with a friend who was a prominent entertainment lawyer. A couple of hours later, Alger returned, laughing. It seems as they were eating, Beatty entered the restaurant. Alger’s buddy waved him over and introduced them, telling Beatty, “You just made Reds, how about a movie on the Hiss-Chambers case?”

“The Hiss-Chambers case?” Beatty answered. “Where’s the love story in that?”

Despite that, I highly recommend the twenty-fifth anniversary DVD. Its terrific cinematography is a great excuse to buy a Blu-Ray player if you haven’t already, and this new version comes with a terrific documentary on the making of the film. Beatty’s comments are marvelous.

Now, here’s The Nation‘s review of Reds, and I thought you’d also enjoy a few of Hugo’s illustrations as they appeared in the magazine in June, July and August, 1936.

Source / The Nation

Thanks to Jeffrey Segal and Mariann Wizard / The Rag Blog

Flat out wonderful stuff!