It both challenged and strengthened my desire to make this a better world, and it caused me to wonder if a better world was even possible.

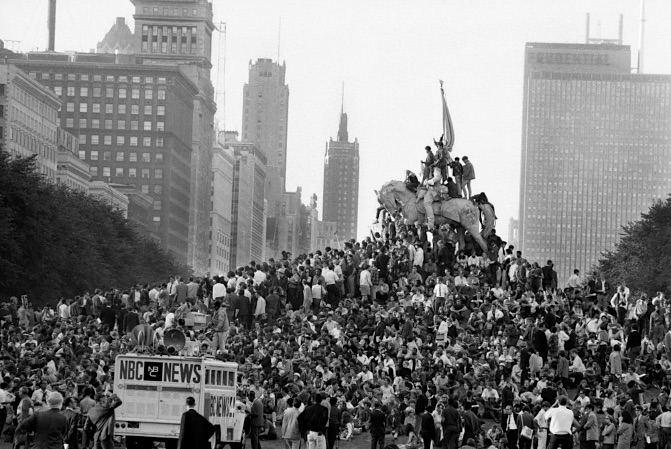

Demonstrators form human pyramid at Chicago’s Grant Park during 1968 Democratic Convention. Historical image from Sky Dancing.

There was one year — 50 years ago — that had more impact on me than any other year in my 73-year life. To say 1968 was a seminal year in the formation of my adult life would be an understatement. It both challenged and strengthened my desire to make this a better world, and it caused me to wonder if a better world was even possible.

But I also learned that there are many good and decent people in the world — and maybe they outnumber the exploiters, the greedy, the self-centered, the unfriendly, the racists, the war-mongers, the mean, the back-stabbers, the hypocrites, the dissembling, the dishonest.

Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA)

After finishing my undergraduate course work in 1967 (I had dropped out of college for a year to serve as a VISTA volunteer in 1965-66), I went to work for a social service agency in Georgetown, Texas. It was largely funded by the Economic Opportunity Act (EOA). We expanded the agency’s reach by creating a VISTA (another EOA program) project, which I supervised, in which about 20 VISTA volunteers served over a few years.

One of the volunteers, with some initial assistance from three architects from another VISTA project, helped six families in Round Rock build their own homes. Two others built a substantial Head Start Center in Bartlett out of wood reclaimed from an old donated railroad depot in Georgetown, which they demolished piece by piece.

Others helped start a community credit union headquartered in Taylor. An employment service was created in Georgetown by a retired VISTA couple. Other VISTAs and several local residents, some of whom became city officials in subsequent decades, developed a neighborhood center in Taylor. A VISTA law graduate set up a legal counseling and advice program. Others worked in tutorial and early childhood education programs.

Young black students were introduced to black history from a non-white perspective.

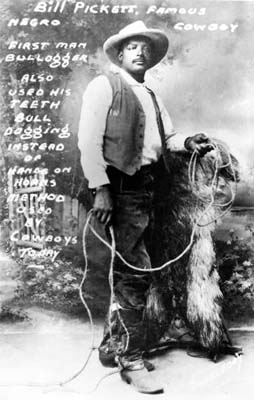

Young black students in Taylor were introduced to black history from a non-white perspective. I learned that the rodeo event of steer wrestling, known also as bulldogging, was created by a black man from Taylor — Bill Pickett. Some of his relatives could still be found in Williamson County 50 years ago and, I assume, today.

(Pickett’s bulldogging creation came about by accident when a bull got loose in downtown Taylor, menacing shoppers and those doing business on Main Street. Pickett chased down the animal, grabbed it by the horns and twisted its neck, using what became his signature move in later bulldogging competitions — he bit the animal on its lip to bring it down.)

The civil rights movement

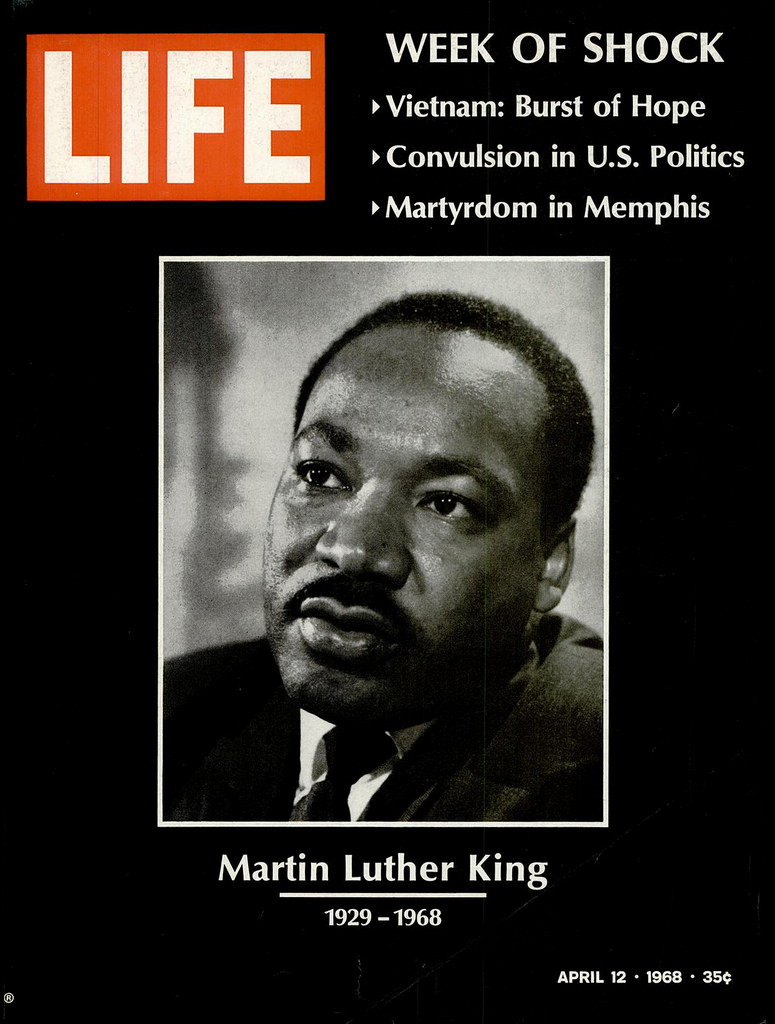

While all of these events and projects started in 1968, other events loomed even larger in my social and political development. After following and participating in the civil rights work championed by Martin Luther King, Jr., since the Montgomery Bus Boycott (I expressed my solidarity with the boycott during my junior high school days in Port Arthur by always sitting in the back of the city bus that I rode to school), 1968 was the year I, along with countless others, mourned his assassination in Memphis, Tennessee.

MLK’s funeral was broadcast

on national television.

He was there to support garbage workers who had gone on strike for better pay and working conditions. His funeral was broadcast on national television. I took off from work to watch the event and cry through a day of paralysis, trying to make sense of what his death meant for the civil rights and anti-war movements, and for me personally.

Conscientious objection and the War in Vietnam

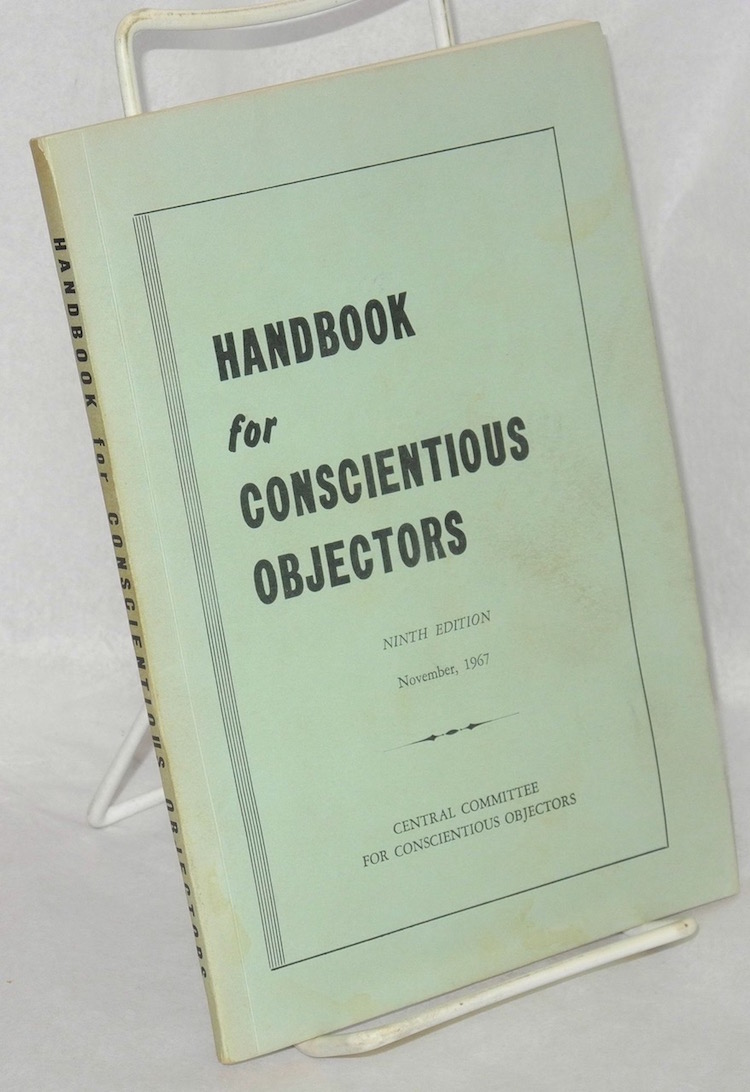

1968 was the year I officially became a conscientious objector (CO). I waited until my draft notice came before filing the paperwork for CO status. I had prepared for this time for several years. In 1965, while working in a migrant worker project as a VISTA in Florida, I had met some Quakers, one of the four historic peace churches, along with the Amish, Brethren, and Mennonites. They influenced my thinking. I devoured the Quaker-created American Friends Service Committee’s pamphlet on how to become a CO.

In preparation for filing as a CO, I solicited letters of support from several minister friends and a contemporary who had served in the military. They attested to the sincerity of my conscientious beliefs opposing war. Much to my surprise, my draft board in Port Arthur approved my application without further correspondence. In similar fashion, they approved the work I was then doing in the social service agency to fulfill the requirement that I perform two years of alternate service to benefit my country. All the preparation I had done in anticipation that the board would want to question me personally turned out to have been unnecessary.

One of my uncles asked me if I became a CO because I was a coward.

One of my uncles, who fought in World War II, asked me if I became a CO because I was a coward, afraid to fight against the Viet Cong. I told him that it wasn’t fear of fighting, but a belief that war was wrong — at least the Vietnam War, which was the form war had taken at that point in my life. I explained that a person does not have to be a pacifist to be a CO. Self-defense is not inconsistent with CO status. I appreciated the lines in Pete Seeger’s 1966 anti-Vietnam War song, “Bring Them Home.”

There’s one thing I must confess

I’m not really a pacifist;

If an army invaded this land of mine,

You’d find me out on the firing line

I had always felt this way, but I agreed also with the boxer Muhammad Ali when he refused to be inducted into the armed forces in 1967, saying “I ain’t got no quarrel with those Vietcong.” I had no quarrel with them either. I knew, from my study about what had happened with the colonialization of Indochina, that France and the United States were wrong to try to control the Vietnamese social and political order and exploit their natural resources. I had also read The Rag [Austin’s ’60s underground newspaper] for over a year, paying close attention to its anti-war articles.

But I had doubts about my decision. I was not sure I had made the right choice, even though I knew that I was fulfilling my values in refusing to serve in the military. It was a decision I struggled with in spite of my moral beliefs. Many years later, when I heard Tim O’Brien discuss an agonizing summer he spent tormented by the draft notice he had received a few months before he went into the Army, I was surprised that he thought it took more courage to refuse to fight in that war than to comply with the government’s order.

I never thought of my decision

as courageous.

I never thought of my decision as courageous. I thought I had no choice if I were to honor my earnestly-held moral beliefs. It was a terrible dilemma — one that I have never satisfactorily resolved in my own mind, partly because I have not forgotten those I knew who died in that war.

While the alternate service I performed may have been valuable to the country in some small way, it never put my life at risk, unless you counted the antipathy of the rednecks and racists we encountered throughout the central Texas counties of Williamson and Burnet. But we had enough support throughout both counties that I experienced little more than an unkind word here and there, perhaps because we served people of every color, including significant numbers of poor whites.

I had friends who went to Canada to avoid the draft, or went to war, or refused all cooperation with the draft system and went to prison. Most had great conflicts within themselves about their decision. There is something about our society that makes these decisions moral watersheds in our lives. I have never regretted my decision, but it still brings back memories of the quandary I felt.

The politics of assassination

My decision to become a CO was made a bit easier by my unrelenting opposition to that war, beginning at least as early as 1965. When Dr. King delivered his powerful speech “Beyond Vietnam” at the Riverside Church in New York City in 1967, exactly one year before his assassination, he buoyed my spirits and my resolve to carry through with my intention to become a CO if I was drafted, even though the speech made him more reviled than had his civil rights work.

I agreed with King that U.S. intervention in Vietnam was naked imperialism.

I agreed with King’s assessment that U.S. intervention in Vietnam was naked imperialism. Because I was working in an agency that was part of the so-called “War on Poverty,” I knew that the Vietnam War diverted money and attention from programs intended to help the poor. He said “the war was doing far more than devastating the hopes of the poor at home… We were taking the black young men who had been crippled by our society and sending them eight thousand miles away to guarantee liberties in Southeast Asia which they had not found in southwest Georgia and East Harlem.” They had not found them in Texas either, an important reason I wanted to do the work I did.

1968 was the year that I understood just how much our government lies to the people. A year before, journalist I. F. Stone had written that “All governments lie.” I had internalized that notion by 1968. But even that realization and all of our history since could not prepare me for the level of deceit, duplicity, dysfunction, and indecency we now witness.

Cover of LIFE, April 12, 1968,

featuring the assassination of

MLK. Image from Flickr /

Creative Commons.

Two months after Dr. King’s assassination, Bobby Kennedy was assassinated in California on the day of the Democratic primary in that state. I had never felt warmly toward Kennedy because of his belated support for civil rights workers who were being killed and maimed, his support for U.S. intervention in Cuba, his support for the Vietnam War before it became a U.S. military conflict, and his late decision to become a candidate only after Eugene McCarthy had done well as a presidential candidate for peace in opposition to the war in the New Hampshire primary.

The accumulation of killings of blacks and civil rights activists took its toll.

The accumulation of killings of blacks and civil rights activists over a five-year period before Dr. King’s assassination took its toll on the spirit of many civil rights supporters and workers, while giving others a fiercer determination to continue in the struggle.

There was Medgar Evers and four young black girls — Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley — in the Klan bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, both events in 1963; the three young civil rights workers James Earl Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Henry Schwerner in 1964; Malcolm X in 1965; Jimmie Lee Jackson, whose death in 1965 led to the Selma-to-Montgomery March; Rev. James Reeb, a Unitarian minister from Boston in 1965; Viola Liuzzo, who provided transportation for Selma-to-Montgomery March participants; and many more whose names are largely forgotten or unknown.

Democratic Party disappointment

Hubert Humphrey went on to become the nominee of the Democratic Party. When he campaigned in Austin, he became the only presidential candidate that I have ever personally demonstrated against. I stood on the steps of the capitol chanting with hundreds of others “Hey, hey, HHH, how many kids did you kill today?” It was not a question that could be answered, but Humphrey had found himself unable to break from Lyndon Johnson’s policy, continuing the Vietnam War. I could not forgive him for that.

Demonstrators were beaten unmercifully during a police riot ordered by Mayor Daley.

I also could not forgive the Democratic Party for not protecting the protesters during the 1968 Democratic National Convention, who were beaten unmercifully by Chicago police during a police riot ordered by Chicago Mayor Daley, a staunch Democrat.

Had George Wallace not run as a candidate of the American Independent Party, Humphrey may have beaten Richard Nixon, though it seems unlikely. The civil rights backlash that enabled Wallace to win five Deep South Democratic states may not have benefited Humphrey even if Wallace had not been on the ballot. Wallace received nearly 10 million popular votes and 46 votes in the Electoral College — votes that Nixon may have captured with an early Southern strategy, in keeping with the white backlash Lyndon Johnson had predicted after the passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts. It is anyone’s guess whether the Vietnam War would have ended any sooner with Humphrey as president than it did under Nixon, with the callous, treacherous, and deceitful manipulation of the “peace process” by Nixon’s Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.

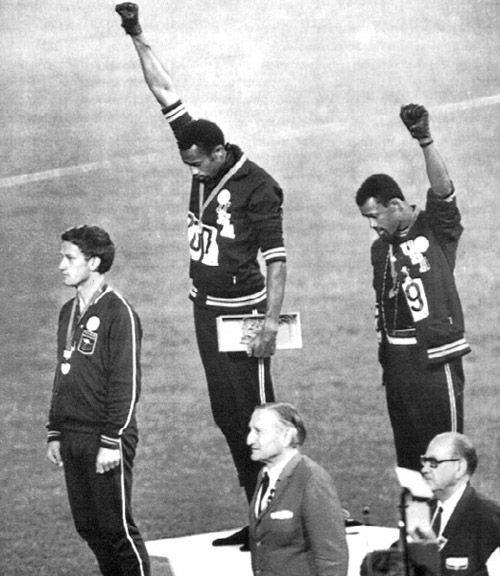

Olympic protest

Finally, during the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, two black athletes — Tommie Smith and John Carlos — staged a silent protest against racial discrimination in the United States and in support of human rights, raising black-gloved fists while bowing their heads during the National Anthem played for Smith’s first-place finish in the 200 meter dash and Carlos’s third-place finish.

They were supported by the second-place finisher, Australian Peter Norman, who wore a pro-human rights badge. Smith and Carlos also wore the badge of the Olympic Project for Human Rights, a group opposed to racial segregation and racism in sports. In addition, Smith and Carlos wore black socks without shoes to symbolize the poverty of so many black Americans, and they wore scarves and beads to protest the countless number of black people who had been lynched and killed because of the color of their skin, including those on slave ships crossing the Atlantic for over 300 years.

Smith and Carlos were stripped of their medals and given life-time Olympic bans.

For their protest, the athletes were stripped of their medals and given life-time Olympic bans. They were treated horribly when they returned to the U.S. In the early years after the Olympics, jobs were hard to find. Carlos’s wife committed suicide because of the pressure they felt. But their protest was warmly received by the African-American community and civil rights supporters of all colors.

They were remembered briefly last fall when Colin Kaepernick engaged in a silent protest against racial inequality and police brutality against blacks during the playing of the National Anthem at NFL games by either sitting or taking a knee. He was cut from the San Francisco 49ers and hasn’t been signed to another team this season, even though his statistics are better than nearly half the quarterbacks who played this past season. But other players from around the NFL, white and black, joined in the protest in spite of threats of disciplinary actions against them from owners and the league.

Reflections on where we are now

In many ways, 2018 is not much different from 1968. Black people can be killed with impunity, sometimes by whites and sometimes by the police, white and black. Prisons are filled with young black men, often for petty crimes, low-level drug offenses, and minor probation or parole violations. We have produced significant changes in race relations and opportunity for all minorities over 50 years, but it is clear that we have a long way to go. We have the most racist president in office in my lifetime — the most racist presidential candidate since the 1968 version of George Wallace, who later renounced his racism. Never in my lifetime have white supremacists and neo-Nazis been welcomed with open arms as they have by President Trump.

The Republican Party, the party of Lincoln, is sullied by its acquiescence in Trump’s racism. Republican politicians and much of the rank and file have shown their true feelings by their warm embrace of Trump. It has become necessary for people of good will to fight racism as hard as we did 50 years ago. We cannot let Trump’s idea of a “Great America” take us back to where we were fifty years ago, or a hundred years ago.

We need to Make America Smart Again, when we the people, through our government, approved the Bill of Rights, emancipation, the 14th Amendment, women’s suffrage, child labor laws, workers’ compensation, industrial safety regulation, food and drug safety regulation, anti-trust laws, banking regulation, Social Security, the GI Bill, the Johnson amendment, the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, Medicaid, food assistance, early childhood education, automobile safety regulation, Medicare’s prescription drug plan, and the Affordable Care Act. And we should be even smarter by improving on these efforts.

We must fight against the pure evil of racism, misogyny, and discrimination against any people, no matter their identity. Another 50 years is too long; another 50 seconds is too long. This nation cannot survive as a democratic republic if we don’t conquer such evils.

[Rag Blog columnist Lamar W. Hankins, a former San Marcos, Texas, City Attorney, also blogs at Texas Freethought Journal and about death and dying at the Good Death Society Blog. This article © Texas Freethought Journal, Lamar W. Hankins.]

- Read more articles by Lamar W. Hankins on The Rag Blog.

Hello Lamar!

Pleased to read your history/memory trip.

Joe Bruch

I’m glad to know that we are both around to remember part of what made us who we are today.

Hi,

I used to live in Houston. I love reading The Rag and promise to send some $$$. I would like to have Lamar’s contact information. I remember him from the NLG in Houston. Thank you and keeping on resisting. I took part in a sit-in to challenge Oakland’s recent curfew and marched at the Juneteenth ILO Shut the port.

Nancy — Why don’t you send your contact info to editor@theragblog.com and I’ll get it to Lamar.

Thorne