How prosecutors and judges let cops get away with murder, or at least with criminally negligent homicide.

The two or three nationwide instances that we have seen recently of holding police to account for their actions are merely anomalies in a criminal legal system that rarely holds law enforcement officers to a standard of justice that we demand from other citizens. Most cops get a pass from judges and prosecutors, and sometimes from juries and grand juries, though grand jurors are usually less culpable because they are led to their decisions by those same biased and compromised prosecutors.

It is not difficult to understand why cops rarely get treated the same as ordinary people accused of crime or who are suspected of having committed a crime. Prosecutors depend on them to make their cases. Arresting officers and investigators from the various law enforcement agencies funnel cases into the criminal legal system, developing a close relationship with prosecutors in the process. They also serve as witnesses for the prosecution at pretrial hearings and in trials. There is a reluctance by prosecutors to prosecute police for misconduct when those same cops work side by side with prosecutors day after day.

Most judges are prone to the same bias that grants

leniency or favoritism to cops.

Most judges with whom I have had contact in the last 50 years are prone to the same bias that grants leniency or favoritism to cops. In my experience, most judges are former prosecutors, who are used to being blinded by the blue (though the uniforms may actually be brown, tan, or gray). Once, I had a judge explain his decision to me, in a candid moment, after he ruled against a defendant after a pretrial hearing in which an officer gave sketchy testimony about what he saw the defendant do that led to his arrest. The judge explained that he could not rule against a cop, even when the evidence suggested that the cop was lying or not telling the whole truth. After all, the judges, prosecutors, and cops were all on the same side–Side A. Defense attorneys and defendants were on the other side–Side B. Even when cops are momentarily placed on Side B, as defendants, they are always understood as being a part of Side A. I think the judge revealed his bias to me because I had represented cops while serving as a city attorney in San Marcos.

In fairness to all the people in the criminal legal system, many are scrupulously honest, follow the evidence wherever it might lead, and hold culpable people to account no matter which side they normally come from. I have been fortunate to encounter many such people, but in my experience the number of people who are not so scrupulous far outweigh the former. A protective pack mentality often overwhelms the impartiality that should exist among law enforcement and the judiciary.

In the past year, many of us have learned of just such a situation. An off-duty San Marcos police officer, Ryan Hartman, killed Jennifer Miller in a vehicle collision in which Hartman was wholly at fault. To date, the criminal legal system has not held Hartman accountable for his grievous misconduct. He was on paid administrative leave for at least 144 days before being reinstated to the San Marcos Police Department without penalty or discipline for his deadly actions. [On January 18, 2022, Hartman was fired from the San Marcos Police Department “as a result of sustained misconduct related to dereliction of duty and insubordination,” not for reasons related to the charge of criminally negligent homicide of Jennifer Miller.]

San Marcos Police Sgt. Ryan Hartman ran a stop sign and struck a Honda Accord driven by Pamela Watts.

On June 10, 2020, San Marcos Police Sgt. Ryan Hartman, while off duty and traveling in Caldwell County on Maple Street going into Lockhart in his F-250 pickup truck, ran a stop sign at the Hwy. 130 feeder road and struck a Honda Accord driven by Pamela Watts, pushing the Accord into a concrete pillar, where it was crushed so severely that the contents could not be inventoried later by Lockhart police. At the time of impact, Hartman was driving 46 mph on a one-lane gravel road. The posted speed limit in that area was 30 mph. Watts was seriously injured and her passenger, Jennifer Miller, was killed in the collision. Watts was airlifted to a large hospital in Kyle; Miller died at the scene some 40 minutes after the wreck. Hartman, physically unscathed, walked away from the crash.

An open 24 oz. container of beer was discovered by law enforcement officers in Hartman’s truck after it was uprighted from its side after the collision, but no breathalyzer test or field sobriety tests were done because Hartman refused to cooperate with the investigation by Lockhart police. According to KSAT News in San Antonio, Hartman “was able to return to duty without being issued anything other than a traffic citation for running a stop sign. Hartman told investigators he was looking at pipeline construction in the area and was distracted by his phone when he crashed into the Accord.”

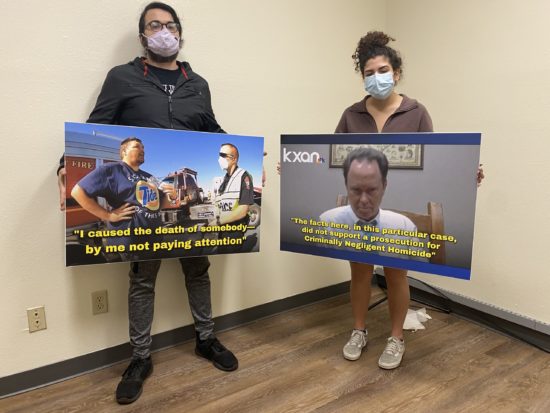

KSAT further reported, “Lockhart police at first indicated Hartman would be allowed to leave from the scene after being treated for minor injuries. ‘Sorry this had to happen today. Accidents happen. You’re in the same line of duty that we are,’ an officer was recorded on his body-worn camera saying to Hartman as Hartman sat in the front seat of an ambulance.” Hartman was quoted by the KXAN news in Austin as saying, “I caused the death of somebody by me not paying attention.”

Hartman identified himself as a San Marcos police officer.

Upon the arrival of Lockhart police officers at the scene of the collision, Hartman identified himself as a San Marcos police officer. After the open container of beer was discovered in Hartman’s truck, Lockhart police officers detained Hartman. A police officer’s video camera recorded the officer pouring out the beer remaining in the beer can. About three hours after Hartman refused sobriety tests at the scene, a specimen of Hartman’s blood was obtained at a Lockhart hospital. The specimen did not show that Hartman had alcohol in his system at the time of the blood test.

Lockhart police obtained data from the computer in Hartman’s truck that showed that Hartman never applied his brakes and accelerated into the Miller/Watts vehicle. In July, Lockhart police investigators filed a charge of “criminally negligent homicide” against Hartman.

Appointment of attorney pro tem and his failure to seek an indictment for criminally negligent homicide

Although Caldwell County Criminal District Attorney Fred Weber initially involved himself in the case in preparation for a grand jury presentation, about six weeks after Jennifer Miller’s death, on July 31, 2020, Weber filed a motion in Judge Chris Schneider’s court to recuse himself and all Assistant Criminal District Attorneys of Caldwell County, Texas, from involvement with any matter concerning the Ryan Hartman case. The apparent reason for the Motion to Recuse was Weber’s prior involvement with Ryan Hartman when Weber worked as an Assistant District Attorney in Hays County, where he had frequent dealings with Hartman, who was a San Marcos police officer.

In his motion, Weber suggested that Bastrop County District Attorney Bryan Goertz or one of his assistants be appointed to present the Hartman case to a Caldwell County Grand Jury. As stated in his Motion to Recuse, Weber had contacted Goertz about such an assignment prior to filing his motion. Surely, if Weber was conflicted out of handling the Hartman case, as he alleged in his own motion, handpicking the person who would be appointed in his stead also posed a conflict of interest.

In addition, an email from Weber to Goertz dated July 31, 2020, suggests that Goertz will be doing Weber a favor if he takes the Hartman case and the favor will be reciprocated at some later date. In spite of his motion to be recused, Weber seemed to see the matter as one for which he is responsible, rather than a matter for a neutral and detached magistrate to resolve.

After Weber’s recusal, Bastrop County District Attorney Bryan Goertz was appointed by Caldwell County District Judge Chris Schneider as Criminal District Attorney pro tem to handle the Hartman case by presenting it to a Caldwell County grand jury. Schneider has a reputation for seeking and taking advice from Weber about his duties as District Judge when considering criminal matters, a field that he had little experience with before becoming a judge.

Information developed in an investigation has shed light on Goertz’s attitude toward criminally negligent homicide.

Information developed in an investigation by reporters for KSAT and KXAN news has shed light on Goertz’s attitude toward criminally negligent homicide and the manner in which he approached his duties in presenting the Hartman case to the grand jury.

Goertz told KXAN he presented a distracted driving case to a Caldwell County grand jury:

I conducted my own review of the investigation of Mr. Hartmann for violation of Texas’s misdemeanor offense of texting while driving and causing a fatality and concluded that no criminal prosecution could be sustained based upon the facts of this case. While the forensic analysis of his phone supported his admission that he was on the phone at the time of the crash (not illegal), there was NO evidence to suggest he was texting.

Instead of focusing on the charge of criminally negligent homicide made by the Lockhart police department against Hartman, Goertz went out of his way to ignore the criminally negligent homicide case law and give his attention to what he described to reporters as distracted driving, which is not a criminal violation in Texas. While distracted driving is related to a texting while driving allegation, such an allegation had not been made against Hartman.

The law of criminally negligent homicide

For anyone trained in the law, there should be no doubt that the charge of criminally negligent homicide was the most appropriate crime to allege against Ryan Hartman. In 2012, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals explained the offense of criminally negligent homicide in Montgomery v. State, 346 S.W.3d 747. In that case, the defendant was driving on an access road to IH-45 in Harris County while talking on her telephone. As she finished the call, she realized she had missed the entrance ramp to the highway. Without checking the lane next to her for other vehicles, she suddenly veered into the left lane causing a three-vehicle collision in which one person was killed. For her failure keep a proper lookout and making an unsafe lane change, resulting in another’s death, she was convicted of criminally negligent homicide.

The court explained the elements of criminally negligent homicide:

To make a legally sufficient showing of criminally negligent homicide, the state must prove that (1) appellant’s conduct caused the death of an individual; (2) appellant ought to have been aware that there was a substantial and unjustifiable risk of death from her conduct; and (3) appellant’s failure to perceive the risk constituted a gross deviation from the standard of care an ordinary person would have exercised under like circumstances. . . . The key to criminal negligence is not the actor’s being aware of a substantial risk and disregarding it, but rather it is the failure of the actor to perceive the risk at all.

Further, the court, citing Williams v. State, 235 S.W.3d 742, 750-51 (Tex. Crim.App.2007), explained that “The carelessness required for criminal negligence is significantly higher than that for civil negligence; the seriousness of the negligence would be known by any reasonable person sharing the community’s sense of right and wrong. The risk must be ‘substantial and unjustifiable,’ the failure to perceive it must be a ‘gross deviation’ from reasonable care as judged by general societal standards. ‘With criminal negligence, the defendant ought to have been aware of a substantial and unjustifiable risk that his conduct could result in the type of harm that did occur, and that this risk was of such a nature that the failure to perceive it was a gross deviation from the reasonable standard of care exercised by ordinary people.'”

Hartman failed to perceive the substantial risk to others by

his negligent driving behavior.

In the Hartman case, the driver was talking on his cell phone; driving at least 16 miles per hour above the posted speed limit; on a one-lane, gravel road; ran a stop sign at that speed; accelerated through the intersection; never applied his brakes; and collided with a vehicle, killing one occupant and grievously injuring another. The negligence displayed by Hartman was at least equal to the negligence discussed in the Montgomery case and exceeds that in most other cases in which Texas courts have upheld criminally negligent homicide verdicts. Hartman, a trained veteran of the San Marcos Police Department, failed to perceive the substantial risk to others by his negligent driving behavior, a risk that any reasonable person sharing the community’s sense of right and wrong would recognize.

As in the Montgomery case, a jury could reasonably find that Hartman’s failure to appreciate the substantial and unjustifiable risk of his driving behavior, “given the circumstances known to him at that time, was a gross deviation from a standard of care that an ordinary person would exercise under the same circumstances,” thus meeting the elements required for a finding of criminally negligent homicide.

In a case similar to Hartman’s, the defendant was convicted of criminally negligent homicide for killing a person in a vehicle collision when the defendant failed to stop at a stop sign and collided with the car in which the deceased was a passenger. Unlike in the Hartman case, no other negligent behavior was reported other than the failure to stop at the stop sign. See Guzman v. State, 760 S.W. 2d (Court of Appeals of Texas, Corpus Christi, 1988).

In Brown v. State, 773 S.W.2d 65 (Court of Appeals of Texas, Fort Worth, 1989) the defendant was convicted of criminally negligent homicide for killing a person when he collided with another vehicle at an intersection after speeding and disregarding a red light.

In Weddle v. State, 628 S.W.2d 268 (Court of Appeals of Texas, Corpus Christi, 1982), the defendant was convicted of criminally negligent homicide for killing three persons when his truck collided with other vehicles at an intersection after “driving at a greater rate of speed than was reasonable or prudent for the conditions” and disregarding a red light.

Had Goertz focused on both the Montgomery case and another case, Queeman v.State, 520 S.W.3d 616 (2017), he might have understood the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals’ explanation of criminal negligence. A person is guilty of criminal negligence if his actions are intentional, knowing, reckless, and are a gross deviation from normal behavior, meaning that the defendant failed to perceive that the risk he was taking was a gross deviation from reasonable care under the circumstances.

For a trained police officer, Hartman’s driving behavior grossly deviated from acceptable driving standards.

For a trained police officer, Hartman’s driving behavior, taken as a whole, grossly deviated from acceptable driving standards based on an accumulation of seven factors: (1) Hartman was distracted by the use of his telephone, (2) was traveling at least 16 miles over the 30 mph speed limit, (3) on a one-lane, (4) gravel road, (5) ran a stop sign, (6) accelerated through the intersection, (7) failed to brake, and (8) had driven through the stop sign-controlled intersection only about ten minutes before the fatal collision. All of these facts were revealed by the Lockhart police investigation into the collision.

The duty of a prosecuting attorney in the grand jury process

Criminal District Attorney pro tem Bryan Goertz failed his duty to the public and to his oath of office in several respects when he presented the Hartman case to the Caldwell County Grand Jury:

a. he failed to present the full facts of the Hartman case to the grand jury;

b. he failed to explain the law of criminally negligent homicide to the grand jury;

c. he failed to educate the grand jury about the law of criminally negligent homicide;

d. he failed to find cases similar to the Hartman case to explain the application of the Hartman facts; and, thereby,

e. he failed to diligently do his duty to represent the state and the interests of its citizens so that justice may be done;

f. he failed to apply the Hartman facts to the law; and,

g. he failed to call before the grand jury Pamela Watts, the only witness to the collision, other than Hartman himself.

Hartman’s driving behavior and actions were at least as egregious as the behavior of the convicted defendants in each of the four cases described above, yet the attorney pro tem appointed by the district court in Caldwell County to present the case to a grand jury failed to seek an indictment of Hartman for criminally negligent homicide.

Hartmann has been a police officer since 2008 and knows the dangers of such driving behaviors better than the average person.

One further factor that can reasonably be used in judging Hartman’s excessive speed on a gravel road, being distracted by a telephone call, and running at an accelerated speed through a stop sign is the fact that he has been a police officer since 2008 and knows the dangers of such driving behaviors better than the average person. Hartman’s failure to perceive the risk at all means that it falls squarely within the bounds of the Montgomery case. Hartman’s actions were “a gross deviation from the standard of care an ordinary person would have exercised under like circumstances.”

Hartman’s driving record

Hartman has been with the San Marcos Police Department since 2008. Subsequent to the collision that killed Jennifer Miller, Hartman has testified under oath about his driving record and other details of his driving record have been discovered. Hartman was involved in nine collisions between 2012 and 2018. He was determined to be at fault or partially at fault in six of those vehicle collisions, involving both personal and law enforcement vehicles.

Subsequent request to the court by Pamela Watts

In November 2021, Pamela Watts [with this author’s pro bono assistance, but not direct involvement] asked Judge Schneider to appoint a new, competent District Attorney pro tem to present properly the criminally negligent homicide charge against Hartman to a new grand jury. One important point Watts made in making her request is based on Article 2.01 of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, which provides in pertinent part, “It shall be the primary duty of all prosecuting attorneys, including any special prosecutors, not to convict, but to see that justice is done.” Bryan Goertz, the prosecuting attorney who handled the case involving the death of Jennifer Miller, failed to do his duty to see that justice was done.

Another section of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure, Article 1.03, provides, “This Code is intended to embrace rules applicable to the prevention and prosecution of offenses against the laws of this State . . .” The section also provides that this code seeks “to exclude the offender from all hope of escape.” Yet the malfeasance of a district attorney pro tem appointed by Judge Schneider has prevented the prosecution of a crime and allowed the offender to escape a fair adjudication of his conduct.

The remedy for Goertz’s malfeasance

Now that this failure of Bryan Goertz to perform his duty as District Attorney pro tem has been brought to the attention of Judge Schneider, he should rectify his earlier appointment mistake by appointing a new District Attorney pro tem who will properly present to a grand jury the charge of criminally negligent homicide against Ryan Hartman. Judge Schneider’s unwillingness to do so is evidence of bias on his part for not acknowledging his role in appointing a person who was not willing or able to properly perform his duty. In addition, Judge Schneider followed the appointment advice of a district attorney who had previously recused himself from the case and should have had nothing else to do with it.

For these reasons, Judge Schneider has ample ethical reasons to recuse himself from further consideration of this case and ask the Supervising Administrative Judge, Billy Ray Stubblefield in Georgetown, to appoint a visiting judge to further handle the charge made against Ryan Hartman by appointing a competent District Attorney pro tem to present the case to a new grand jury.

The only way the people can have confidence in the criminal legal system is to assure that charges against police officers are properly considered, that is, handled in the same manner and to the same standards as those applied to defendants who are not members of law enforcement. The primary charge of criminally negligent homicide lodged against Ryan Hartman by the Lockhart Police Department has not been properly handled within that legal system. It is time for everyone, including judges, to stop being blinded by the blue and prevent a further miscarriage of justice.

[Rag Blog columnist Lamar W. Hankins, a former San Marcos, Texas, City Attorney, is retired and volunteers with the Final Exit Network as an Associate Exit Guide and contributor to the Good Death Society Blog.

- Read more articles by Lamar W. Hankins on The Rag Blog and listen to Thorne Dreyer’s Rag Radio interviews with Lamar.