A tale of Civil War Texas:

The battle and massacre at the Nueces River

The German Freethinkers in the Hill Country stood up for their beliefs in the face of hostile, organized, and armed opposition.

By Lamar W. Hankins | The Rag Blog | August 15, 2012

Among Civil War battles, the fight that has come to be known to many as “The Battle of the Nueces” was not very important, but it may be one of the most controversial battles, because of its characterization by Civil War historians and aficionados — Was it a battle or a massacre? From my research, it appears to have been a massacre within a battle.

It occurred 150 years ago on August 10, 1862. But the story begins around 1848, when about 1,000 freethinking Germans immigrated to the Texas Hill Country, mostly to the area between and west of San Antonio, New Braunfels, and Fredericksburg.

About 20,000 German Freethinkers (Freidunker in German) immigrated to the U.S. around 1848 to escape political and religious persecution in Germany. They included prominent doctors, writers, newspaper publishers and reporters, philosophers, scientists, engineers, and inventors. While many consider the Freethinkers atheists or agnostics, a more apt characterization is that they viewed the idea of a diety as irrelevant to their lives.

Ed Scharf’s research on Hill Country Freethinkers found that they took political and social positions that could be considered anti-authoritarian, democratic, and communitarian by today’s standards. These Freethinkers were products of the Enlightenment. They revered science and intellectual pursuits, and they opposed superstition. They were intolerant of abuses by both the church and the state.

Scharf reports that in San Antonio, at an 1854 Saengerfest, a singing convention which the German Freethinkers held annually, they adopted resolutions which, among other things, demanded

- laws to be enacted, so simple and intelligible, that there should be no need of lawyers

- the abolition of the grand jury

- the abolition of capital punishment

- the abolition of all temperance laws

- taxation based on level of income — the greater the income, the greater the tax

- the elimination of religious instruction in schools and preachers as school teachers

- the abolition of laws respecting Sunday or days of prayer

- the abolition of a religious oath

- an end to opening Congress with prayer

The Freethinkers also opposed slavery and stood on the side of the Union, as did Sam Houston, the first president of the Republic of Texas. After Texas was annexed by the United States in 1845, Houston became a U.S. Senator. During a debate in the Senate over several bills known as the Compromise of 1850, Houston said, “A nation divided against itself cannot stand,” a sentiment echoed eight years later by President Abraham Lincoln. However, most German immigrants to the southern U.S. did not follow Houston’s and the Freethinkers’ lead — they supported the Confederacy.

German Freethinkers were prominent in the Hill Country and beyond. They could be found in the Texas counties of Kendall (Comfort, Sisterdale, and Tusculum), Llano (Castell), Colorado (Frelsburg), Washington (Latium), DeWitt (Meyersville and Ratcliffe), and Austin (Millheim and Shelby). A German Freethinker, Dr. Carl Adolph Douai, published the San Antonio Zeitung, a newspaper dedicated to social progress and fiercely opposed to slavery and secession. In 1855, the newspaper offices were destroyed by people opposed to the views regularly expressed in the newspaper.

In 1861, German Freethinkers in the Texas Hill Country around Comfort and Fredericksburg organized the Union Loyal League to oppose secession, provide protection from Confederate soldiers who patrolled the area between their encampment near Fredericksburg and San Antonio, and to protect settlers against outlaws and hostile Indians (though many Indians interacted with the settlers peaceably).

Some members of the League were strong supporters of the Union and celebrated Union victories that they learned about. By mid-1862, the League had an estimated 500 members who were armed with conventional weapons of the time — pistols, shotguns, and rifles.

The League clearly hoped to restore Federal power to the region when the Civil War ended, and they wanted “to prevent the forced enrollment of Unionists in the Confederate Army.” Some in the League threatened people who sided with the Confederacy. League members shared information through “an underground communication system” and encouraged the Union to invade Texas.

If an invasion did occur, the League planned to help Union forces, including freeing Union sympathizers who had been imprisoned and fighting Confederate units. Because of these threats, the Confederate government located in Austin organized a detachment of state militia forces and Confederate cavalry forces to patrol the Texas Hill Country.

These patrols were given the task to locate and capture any men in arms against the Confederacy and to keep order among those who resisted the recently enacted Confederate Conscription Act, which required all men between the ages of 18 and 35 to pledge allegiance to the Confederacy and serve in the Confederate Army. The detachment, under the control of Captain James Duff, was bivouacked near Fredericksburg.

Duff had been a member of the state militia before receiving a commission as captain in the Confederate army. His unit left the Fredericksburg area in June, but in July Duff was given command of four companies to return to the area to put down what was believed to be open insurrection by Hill Country Unionists. Duff was appointed as provost marshal for the area. In late July, Duff proclaimed martial law in Gillespie County and in portions of other adjacent counties.

Even many of Duff’s men considered him ruthless in his harassment of Unionists in Gillespie, Kerr, Kendall, Edwards, and Kimball Counties. Consequently, many League members decided to flee the state because of their political views, to avoid conscription into the Confederate Army, and for personal safety.

One of their leaders, Frederick Tegener, an organizer of the Union Loyal League, reported that he had read a proclamation stating that Texas Governor Francis Lubbock had ordered that those men who could not follow the requirements of the Confederate Conscription Act would be given 30 days to leave the state, though no documentary evidence of such an order has been found.

On August 1, 1862, 80 German men met at Turtle Creek, 18 miles west of Kerrville. Sixty-one decided to flee to Mexico. From there some of the men thought that they could make their way to New Orleans, which had been taken by Union forces on May 1, 1862, to join up with the Union army.

During the next two days, the men left their homes to head toward Mexico by way of Devil’s River, led by Frederick Tegener and accompanied by a non-German, John W. Sansom. Probably two spies in their midst reported the departures and plans to Duff, who dispatched 96 men under the leadership of Colin D. McRae to pursue them. Leaving on August 3, they tracked the fleeing Unionists from the Pedernales River, down the Guadalupe.

At some point, another five men (four Anglos and one Mexican) joined the Unionists in their trek to Mexico. The men continued down the Medina and Frio Rivers until they reached a bend in the Nueces River. There they decided to camp on the night of August 9.

The pace for the trip had been leisurely, with reports of target practice and wood carving by some of the men as they made their way toward Mexico, which was only one day’s ride from their campsite on the Nueces.

Hunting parties sent out by the Unionists from their Nueces camp reported seeing unidentified riders on the Unionists’ backtrail, but neither Tegener nor any of the other Unionists seemed concerned, apparently not realizing that they were being hunted down by Duff’s troops. The Unionists were so unconcerned with safety that they did not even post sentries for the night.

When the Texas Confederate forces neared the Unionists’ encampment, they prepared for an assault on foot and split into two groups to attack the Unionists from two sides. They planned to attack during the night and were in place by 1 a.m. A gun shot was to be the signal to begin the assault.

Two of the Unionists wandering from the encampment during the night, stumbled upon one of the groups of Confederate forces around 3 a.m. and killed one of the men. That shot was thought by the Confederates to be the signal to attack, and the battle began with sporadic fighting and re-positioning of forces by the Confederates during the night.

Before dawn, 23 Unionists escaped the encampment through McRae’s scattered forces to return to their homes. That increased the Confederates’ advantage considerably. At dawn the Confederates slowly made their way toward the Unionists who remained.

During this initial battle, two Confederates were killed and 19 more wounded. McRae was wounded with two shots. Twice the Confederates were made to fall back by the determined fighting of the Unionists, but a final charge by the Confederate forces killed, wounded, or scattered the remaining Unionists.

When the fighting subsided early in the morning, some of the Confederates attended to their own wounded and to wounded Unionists. Some of the men cooked breakfast. Immediately after the fighting ended, according to the eyewitness account by Confederate fighter R. H. Williams, “a couple of boys were sent off, post haste, to Fort Clark,” about 30 miles away, to get medical help for the wounded.

In the late afternoon, after tending to the needs of some of the wounded Confederates, Williams decided to check back on the wounded Freethinkers, but found they had been moved. A group of Confederates, taking directions from Lt. Edwin Lilly (whose name has also been reported as Luck) moved nine to 11 of the wounded Unionists into a cedar thicket under the excuse that they needed to be in the shade.

Williams started to go see to them when he heard a number of shots fired. Lt. Lilly had had all of them summarily executed with shots to their heads. Williams wrote that he considered it a cowardly and despicable act, and that the Lieutenant was a “remorseless, treacherous villain,” which he told him to his face.

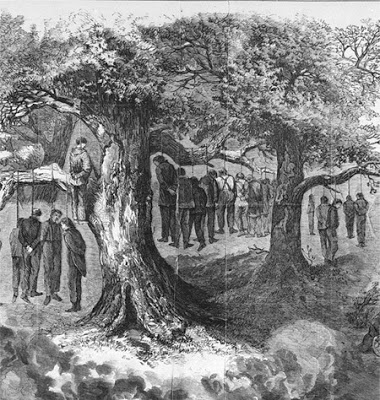

The Confederates buried their dead in a long trench, but left the bodies of the dead Unionists to the vultures, coyotes, and wolves. Nine other Unionists were pursued by various units of Confederates and state troops and shot or hanged within two weeks of the Battle at the Nueces, but it is unclear from the historical record how many of them had been at the Nueces battle.

In 1865, a group of family and friends of the dead Unionists made their way to the battle site and recovered the remains of the Unionists. The remains of 36 Freethinking Unionists were buried at Monument Hill in Comfort, Texas, where a memorial — called the “Treue der Union” (loyalty to the Union) — was erected in their memory.

Harper’s Weekly, in 1866, described the burial ceremony as including a military honor salute “without any religious fanfare.” After the Civil War ended, German Freethinkers scattered throughout Texas, many moving to urban areas and continuing to make significant cultural, social, and political contributions to the state.

The German Freethinkers in the Hill Country stood up for their beliefs in the face of hostile, organized, and armed opposition. They adopted the same tactics against the Confederacy, a course they believed was their only hope for survival. Even in their efforts to leave Texas and avoid conscription into the Confederate Army, nearly 70 of the Freethinking men were tracked down and most were killed by Confederate forces.

When all the facts are known, it seems clear that the Battle at the Nueces River was not unlike many Civil War battles, with one difference: it included a massacre of wounded men that was unnecessary and considered vicious retribution by many. In 1929, the Dallas Morning News referred to the massacre within the Nueces battle as “The Blackest Crime in Texas Warfare.”

[Lamar W. Hankins, a former San Marcos, Texas, city attorney, is also a columnist for the San Marcos Mercury. This article © Freethought San Marcos, Lamar W. Hankins. Read more articles by Lamar W. Hankins on The Rag Blog.]

[SOURCES: Paul Burrier, an independent historian of the Battle at the Nueces, of Leakey, Texas — interviewed February 29, 2012; Edwin E. Scharf, ” ‘Freethinkers’ of the Early Texas Hill Country,” published in Freethought Today, April 1998; Stanley S. McGowen, “Battle or Massacre?: The Incident on the Nueces, August 10, 1862,” published in The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 104, July 2000-April 2001; Robert W. Shook, “The Battle of the Nueces, August 10, 1862,” published in The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 66, July 1962-April 1963; Dominque De Cleer (translated into English by Gerald Hawkins), a tract titled “Victory Without Heroes on the Nueces” published by the Confederate Historical Association of Belgium; Joe Baulch, “The Dogs of War Unleashed: The Devil Concealed in Men Unchained,” published by the West Texas Historical Association; Egon Richard Tausch, “Letter From Texas: Gott Mit Uns,” published in Chronicles: A Magazine of American Culture, August 2007; Irene Van Winkle, “Myth, fate clash around Tegener’s role in Unionist movement, published by the West Texas Current, March 10, 2012; R. H. Williams (who fought in the battle on the Confederate side) and John W. Sansom (who fought with the Freethinkers but escaped before the battle ended and later was a Texas Ranger), “The Massacre on the Nueces River: The Story of a Civil War Tragedy,” published by the Frontier Times Publishing House]