No one wins when government

forces religion on everyone

If public officials believe that religious worship is important, perhaps they should meet in a conference room before the meeting and pray together with their chosen clergy.

By Lamar W. Hankins | The Rag Blog | November 14, 2012

SAN MARCOS, Texas — Those who see no harm in beginning a meeting of a city council, school board, or commissioners court with prayer owe it to the Constitution to take a few minutes and consider the perspective that the First Amendment’s prohibition against an establishment of religion means that the government is not allowed to force any religion — or religion itself — on its citizens.

For the moment, I will put aside the issue of sectarian versus nonsectarian prayer and focus on any prayer, whatever its content. Put simply, prayer is communicating with God or gods. Prayer is an act of religious worship. It is the most universal form of religious practice that I know of. There should be no doubt that prayer is a religious practice: people who are not religious or do not believe in the supernatural do not pray. Only religious people pray.

The prayer invocations regularly offered before meetings of government bodies are usually directed toward a deity, spirit, or amorphous supernatural being. They often express everyone’s reliance on the being and their desire to please said being. Usually they request guidance or help from the being and occasionally ask for special favors, such as rain or assistance for improving the performance of a favored athletic team.

When the government sponsors, promotes, or establishes prayer as a part of its activities, it is sponsoring, promoting, or establishing a religious practice, an integral part of religious worship. If any person wants to participate in the civic life of the community by attending, speaking at, or observing the meetings of elected officials who begin their meetings with prayer, that person must submit to a religious practice.

If the Supreme Court has been clear about anything in this area of jurisprudence, it is that the government may not sponsor, promote, or establish religion or religious practices, although it has permitted prayer not identified with a particular religion (nonsectarian prayer), because it views such prayer as insignificant, if not irrelevant.

For most elected officials, it seems that having an invocation before a meeting of a government body means offering a prayer. But “invocation” need not be so narrowly construed. Merriam-Webster defines invocation in other ways: “the act or process of petitioning for help or support” and “a calling upon for authority or justification.” Neither of these definitions necessarily suggests that an invocation be addressed to a god.

An invocation can be addressed to the governing body (rather than to a deity), to remind its members of their responsibility to serve the greater good; to respect the dignity of all citizens; to show no favoritism based on personal interest, race, religion, or party affiliation; to be open to the ideas of others; to use reason devoid of cant and deceit; to display compassion when that is needed; to seek answers to our problems through the ingenuity of our people; and to honor other ideals inherent in our history. An invocation need not be an act of religious worship or practice.

When it comes to fashioning an invocation for a home-rule city like the City of San Marcos, its charter will provide specific responsibilities of the city council that should be carried out, the goals of the city, the proper behavior expected of city officials, and any general standard that should always be kept in mind, such as “devotion to the best interest of the City.” There is no better way to help public officials always be aware of why they were elected than to regularly remind them of their proper role as found in their local constitution.

If an invocation is intended to set a tone for a meeting of our elected leaders, these suggestions seem to accomplish that purpose, and they do so without engaging in any religious practice or worship. If they express opinions about how the body or its citizens should act that the listener disagrees with, that listener should be able to get on the invocation list and offer a non-prayer invocation that he or she believes is more in keeping with our shared values and the purpose of the governing body.

Part and parcel of the prayer problem is limiting who may give invocations to clergy. Clergy are expected to pray. That is why they are invited to give the invocation. All of the official invocation policies that I have seen single out clergy to provide the invocations — clear evidence that the purpose of the invocation is to engage in the practice of religion.

Many of our elected representatives are religionists first and public officials second. It should be the other way around. Religionists want to use the government to impose their religious beliefs on the rest of the population, ignoring the rights of all citizens to have the autonomy to make their own religious and moral decisions.

This was the case with both the Hays County Commissioners Court and the San Marcos City Council. When Jim Powers began his tenure as Hays County Judge and Susan Narvaiz began her tenure as Mayor of San Marcos, both decided for their own religious reasons to have their respective governmental bodies begin using prayers to start their meetings. They used their public positions to have the government promote their private religious beliefs. For many decades, both bodies had functioned just fine without the prayerful invocations.

Having the government force religious positions on other people has always created great turmoil in society, and it has corrupted both the government and the religious groups involved. For these reasons, the drafters of the Constitution sought to keep government out of religion.

They had seen what happened in England to religious liberty when the state and religion are intertwined, and they had witnessed the disorder, dissension, and destruction brought about in various colonies by an alliance between government and religion. James Madison was aware also of the example of Holland where religion and government were kept separate so that each person had full religious freedom and freedom of conscience.

Even the Texas Constitution, in spite of its frequently inappropriate religiosity (much of which has been invalidated by the Supreme Court as infringing on the guarantees and provisions of the U.. Constitution), provides that no one “shall be compelled to attend, erect or support any place of worship, or to maintain any ministry against his consent. No human authority ought, in any case whatever, to control or interfere with the rights of conscience in matters of religion, and no preference shall ever be given by law to any religious society or mode of worship.”

This is precisely what religious prayers as invocations do to all the citizenry. They maintain a ministry without the consent of all those who want to participate in local government. They interfere with the right of conscience in matters of religion. They give preference to certain religious groups and subject those in attendance at meetings to religious worship.

Those who suggest that anyone who disagrees with the prayers can absent themselves from that part of the meeting have not thought fully about this suggestion. The way the San Marcos City Council functions, for instance, it is not possible to know when the invocation will be held. The Council often begins meetings with lengthy workshops, starts the business meeting by convening into executive session, delays the invocation until after other business is conducted, or waits until the clergy scheduled to give the invocation arrives at the meeting.

Should the Mayor announce in advance that a moment will be given for all those who don’t want to engage in prayer to leave the room? Will that person’s seat be saved or taken by another during the person’s absence? Avoiding the prayer requires leaving the building because the meeting is broadcast outside the council chambers for those who can’t find a seat or want to stay in the foyer. Who will tell those who have left the building when the prayer is over?

But the very suggestion that those not wanting to engage in a religious practice can leave the meeting is to acknowledge that the activity is religious activity, which should not be sponsored, promoted, or established by a government body under the Constitution.

I have never understood the mindset of public officials who believe that they have the right as elected officials to impose their religion and religious practices, or anyone’s religious practices, on the citizens by virtue of their public positions.

The author, editor, political commentator, and blogger Andrew Sullivan is a devout and ardent Roman Catholic. In a colloquy with atheist author and neuroscientist Sam Harris in 2007, they addressed the question of how a person of such strong belief as Sullivan can resist inflicting his religious beliefs on others. His answer is relevant to elected officials who assume the right to do this very thing to us all.

Sullivan responded to the question posed:

You ask legitimately: how can I, convinced of this truth (about Christianity), resist imposing it on others? The answer is: humility and doubt. I may believe these things, but I am aware that others may not; and I respect their own existential decision to believe something else. I respect their decision because I respect my own, and realize it is indescribable to those who have not directly experienced it.

That’s why I am such a dogged defender of pluralism and secularism — because I believe secularism alone does justice to the profundity of the claims of religion. The attempt to force or even rig laws to encourage others to share my faith defeats the point of my faith — which is that it is both freely chosen and definitionally dealing with matters that cannot be subject to common consensus.

If public officials believe that religious worship is important, perhaps they should meet in a conference room before the meeting and pray together with their chosen clergy. Then, filled with righteousness from their religious worship, they can enter the meeting room in the frame of mind of their choice, gavel the meeting to order, and get on with doing the people’s business, without subjecting the people to forced religious worship.

In this way our elected officials can show respect for the pluralism of this society, the U.S. Constitution, and the conscience of every citizen.

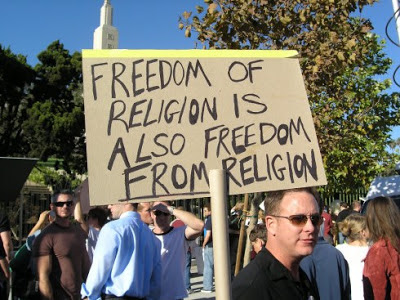

The Bill of Rights became a part of our Constitution over 220 years ago. It is time that all of the First Amendment of that Constitution was followed. No one has a constitutional right to use the government to sponsor, promote, or establish religion; but everyone has the constitutional right to be free from government sponsorship, promotion, or establishment of religion.

It should not be too much to ask that this freedom be honored. That would be true religious liberty for all.

[Lamar W. Hankins, a former San Marcos, Texas, city attorney, is also a columnist for the San Marcos Mercury. This article © Freethought San Marcos, Lamar W. Hankins. Read more articles by Lamar W. Hankins on The Rag Blog.]

As a theist become non-theist, I have found a way to open or close meetings in a meaningful way without treading on anyone’s beliefs or lack thereof. I “pronounce a blessing” that could very well contain some of the ideas you mentioned: “May our elected officials be blessed with the wisdom needed to serve.” Or perhaps: “May this meeting be without contention, and may all discussions keep the best interests of our city at heart.” Those who are religious will probably hear these as requests of a deity, yet an atheist could buy into the ideas, too.