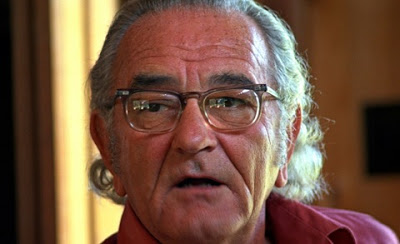

| Former President Lyndon Baines Johnson, August 1972. Image from the LBJ Library / PBS Newshour. |

Lyndon Baines Johnson:

My tragic hero

LBJ was doomed from the start, trapped by earlier mistakes that he could not avoid without being vilified by the political opponents and war hawks in his own party as well as by Republicans.

By Lamar W. Hankins | The Rag Blog |April 8, 2013

The recent unveiling of a monument to honor Vietnam veterans at the Texas state Capitol in Austin rekindled my memories about President Lyndon Baines Johnson — known widely as LBJ. Both of his daughters participated in the ceremony marking the groundbreaking, which included reading the names of all 3,417 Texans who died in that war — some of whom I knew. I loved LBJ for his championing of civil rights and the War on Poverty.

But the War in Vietnam was his downfall and led to my partial disaffection with him.

It may seem overblown to call LBJ my tragic hero, but in a real since he was — at least in the Aristotelian sense.

For those who didn’t live through the 1960s, it may be difficult to imagine what it was like for someone who went from teenager to young adult in that span of years. I was an active participant in the civil rights movement while in high school in Port Arthur, a town whose inhabitants were as racist as any in the South, but with a Cajun twist that sometimes took the edge off because of the intermixing that occurred in parts of neighboring Louisiana, where many of our residents came from.

But make no mistake — racism was rampant among whites, even if some of the vitriol was absent.

LBJ became a friend of the civil rights movement because he felt the movement’s pressure, he understood history, and he knew that racism was wrong. Without him, it is doubtful that the civil rights acts of the mid-60s would have passed as soon as they did.

The two oldest Kennedy brothers were reluctant to act decisively about civil rights except under extreme pressure. John F. Kennedy did not have the legislative abilities that LBJ possessed. It is unlikely that the public accommodations and voting rights acts would have passed in 1964 and 1965 if JFK had been president.

I am regularly reminded that the role of our military is to preserve our freedoms. But that wasn’t what the military was doing in the Vietnam War. That war had nothing whatever to do with our freedoms, but it did concern our misunderstanding of the rest of the world and the widespread belief that the United States has been called by God to control and fix the rest of the world through our overwhelming military and economic power.

A recent Gallup poll reports that Americans have greater confidence in the military than in any other of our institutions. This does not surprise me for several reasons. The military taps into the emotion called patriotism more than any other institution of government. The media give the military enormous publicity and rarely push back against military decisions.

The World War II generation has been hailed as “The Greatest Generation” because of its defeat of Hitler and Japan and the successful expansion of the economy and the middle class for several decades after the war.

But I have never shared that level of confidence in the military. The incestuous relationship between high military brass, politicians, and the corporations that feed off our taxes that support the military seems to fulfill the very definition of corruption.

Decades ago, the Pentagon developed a strategy to put some sort of military installation or award contracts for military hardware and supplies in every congressional district in the country. Consequently, most politicians provide unquestioning support for keeping military expenditures higher than the combined military expenditures of the next highest-spending 14 countries. And those expenditures make wealthy the corporations who build the military hardware and look after the military’s needs.

During the Vietnam War, I knew young men who were drafted into the military, but I also knew several who fled to Canada to avoid the draft, others who became conscientious objectors, and one who went to prison for refusing to cooperate with the draft.

I was a conscientious objector and performed alternate service for my country for two years, serving in LBJ’s War on Poverty, and I spent almost 10 more years in that same effort, living for one year on poverty wages and working for three and a half years as a Legal Services attorney.

During the Vietnam War, with help from the American Friends Service Committee, I provided volunteer counseling to young men who thought that they might qualify as conscientious objectors. My motivation during those years was to try to reduce the number of young men who were sent off to be what I regarded as cannon fodder for the war against the Vietnamese, a country that had done us no harm, and had already driven the colonialist French out of that part of the world.

To be a conscientious objector, however, is not to be a pacifist. I was delighted by some verses in a 1966 Pete Seeger song — “Bring Them Home” — that made this clear:

If you love your Uncle Sam,

Bring them home, bring them home.

Support our boys in Vietnam,

Bring them home, bring them home.

…There’s one thing I must confess,

Bring them home, bring them home.

I’m not really a pacifist,

Bring them home, bring them home.

If an army invades this land of mine,

Bring them home, bring them home.

You’ll find me out on the firing line,

Bring them home, bring them home.

At the time, nothing expressed so simply and elegantly how I felt and how I feel still. But I have never been associated with any organization that advocated violence, except for my 30-year dalliance with the Democratic Party, which ended in 1992.

I have read some of Tim O’Brien’s Vietnam War-themed books and heard him lecture a couple of times. One point that O’Brien makes in his lectures and discusses in one of his books — The Things They Carried — is that deciding to go into the military after being drafted was one of the most morally difficult decisions a young man could make. O’Brien believes that the more difficult and the more courageous decision was to oppose the draft, whether by fleeing to Canada, refusing to cooperate, or by becoming a conscientious objector. I always felt the opposite was true.

When I told my family that I had become a conscientious objector and that my application had been granted and I was ordered to do alternate service for two years, one uncle asked me if I did that because I was afraid to go fight. I had to explain to him that it was not fear that drove my decision, though one would have to be non-human not to have some fear, but it was a moral objection I had to war that I had thought about for several years. I don’t know if my uncle accepted my explanation, but he dropped the subject.

That was the same year that LBJ announced that he would not accept the nomination of his party to be a candidate for president. I have listened to some of LBJ’s archived conversations with friends and associates about the Vietnam War. I know that he agonized over what he had done in persuading the Congress to escalate the conflict, but he felt trapped by circumstance.

LBJ inherited American military involvement in Vietnam that began when Harry Truman promised the South Vietnamese that he would not let the South be taken over by the communist North. Kennedy increased our troops in Vietnam to 16,000 by 1963. LBJ could not find a way to keep Truman’s promise or get U.S. troops out of Vietnam, while preserving his and the country’s honor as he understood that term. This misguided code of honor, I believe, was his fatal flaw.

For Aristotle, the tragic hero was someone of noble stature, outstanding ability, with a greatness about him a “great and good man.” Clearly, LBJ was such a man. His skills as a legislator have been unsurpassed during my lifetime. When he was suddenly thrust into the presidency after the assassination of President Kennedy, he was prepared. He needed no on-the-job training. In the first few weeks after taking office, he gave the country confidence that he would keep the country together and accomplish important work.

In Vietnam, LBJ’s purpose (however misguided) was the same as Truman’s, Eisenhower’s, and Kennedy’s: to defeat the spread of Chinese communism. As we have seen, even after our defeat in Vietnam, Chinese communism did not spread there. The so-called Domino Theory had no substance, though it sounded logical to many.

But Americans tend to look at the rest of the world through their own lens, which may have no relationship to reality. Our presidents and foreign policy experts have made similar mistakes over and over. And these people supposedly are our best and brightest. Their own hubris feeds that of our presidents, and of our citizens.

LBJ was doomed from the start, trapped by earlier mistakes that he could not avoid without being vilified by the political opponents and war hawks in his own party as well as by Republicans. The military-industrial complex that Eisenhower had warned about as he left office had already become an inescapable force that even our most skillful politician could not overcome.

As the Iraq War and the Afghan War’s frequent transformation and escalation over 11 years have demonstrated, wars are not as easy to get out of as they are to get into. Perhaps President Obama has found a narrative about Afghanistan that will allow him to escape the trap that LBJ could not escape in Vietnam.

But President Obama is not prepared to completely leave Afghanistan. He plans to leave a contingent of troops there and elsewhere in the Middle East to continue fighting terrorism using a special forces strategy aided by drones, even though that fight no longer has anything to do with the perpetrators of 9/11, which was the basis for the authority Congress gave President Bush to attack Afghanistan.

Since I was in kindergarten nearly 65 years ago, I have watched people in positions of authority wield power in varying ways. Sometimes, their exercise of power has been wise and the results beneficial; often times not. Every president who has served during my lifetime has made some extraordinarily bad decisions. Most of them have been based on the idea that America is exceptional and has some birthright to control the world. Without question, this idea was behind the Vietnam debacle. But it was pride (and politics) that made it so difficult for LBJ (and later Richard Nixon) to extricate us from Indochina.

While I often say I don’t have heroes, LBJ was a tragic hero for me. Unless American politics undergoes a radical change, it won’t be long before another American president will play the same role that can lead only to tragedy both here and abroad.

[Lamar W. Hankins, a former San Marcos, Texas, city attorney, is also a columnist for the San Marcos Mercury. This article © Freethought San Marcos, Lamar W. Hankins. Read more articles by Lamar W. Hankins on The Rag Blog.]