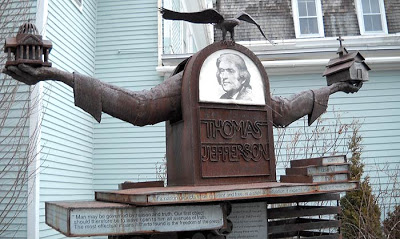

Thomas Jefferson,

the San Marcos City Council,

and the municipal promotion of prayer

It is a feeble and flaccid religion that needs the imprimatur of government to find its relevance.

By Lamar W. Hankins / The Rag Blog / May 17, 2011

SAN MARCOS, Texas — City councils have no jurisdiction over religion, yet throughout Texas and the rest of the country, they promote it, sometimes fervently. While city councils have no power to deal with religion, they love to use religion’s reflected glory to enhance their own status.

When government officials meddle in religion, they lose all perspective and begin to see themselves as righteous and doers of God’s will, even in every zoning change they approve, every no-parking zone they create, and every pothole they order filled.

These council members reject Thomas Jefferson’s view that it is not in the “interest of religion to invite the civil magistrate to direct its exercises, its discipline, or its doctrine.” Ignoring this view, city councils are sponsoring prayer at the beginning of their meetings as though they have some ecclesiastical mandate to promote such religious exercise.

They quarrel regularly with the author of the First Amendment, James Madison, who stated, “There is not a shadow of right in the general government to intermeddle with religion. Its least interference with it would be a most flagrant violation.”

When President Andrew Jackson was asked to proclaim a national day of prayer and fasting, he said he could not do so “…without transcending the limits prescribed by the Constitution for the President and without feeling that I might in some degree disturb the security which religion nowadays enjoys in this country in its complete separation from the political concerns of the General Government.”

Many mayors and city council members don’t believe that they should have such limits.

Historian R. Freeman Butts reports, “Virtually every state as it came into the Union in the nineteenth century adopted the principles that the state guaranteed freedom of religious conscience and that the state would not use public funds to aid or support any churches or their schools.”

But city councils in all parts of the country regularly use their offices, public property, public employees, and public resources to promote religious activity–namely, prayer.

Dozens of cities over the last few years have been challenged regarding their sponsorship of prayers, especially Christian prayers. The best advice many of these city councils have received is to adopt policies that establish only non-sectarian prayers. The City of San Marcos, Texas, in 2009, was challenged about its prayer policy by Americans United for Separation of Church and State and the ACLU of Texas. In response, the city council adopted a policy that approved only prayers that do “not advance any one religion, disparage any other religion,” or are used to proselytize.

The new policy, adopted in August 2009, was based on the leading Supreme Court decision on the subject, Marsh v. Chambers. In following the Marsh decision, in 2004, the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals held that any sectarian invocations of deities in legislative prayer demonstrate affiliating the government with a particular sect or creed and/or advancing a particular faith or belief: “Marsh does not permit legislators to… engage, as part of public business and for the citizenry as a whole, in prayers that contain explicit references to a deity in whose divinity only those of one faith believe.”

This decision effectively prohibited sectarian prayers, yet the City Council of San Marcos continues to promote mostly Christian prayers offered as invocations.

One flaw in the San Marcos scheme is that it establishes the City Council as the purveyor of a privilege to practice religion in its chambers as a part of official government business, a notion that eats at the heart of the First Amendment’s prohibition against an establishment of religion.

In addition, the policy limits invocation participants to “clergy,” though this provision is ignored at the will of the council or its mayor or city clerk, who is given the responsibility to implement the prayer scheme. For example, several non-clergy associated with one religion or another have been allowed to offer invocations.

But the policy limits participation to those who represent a “faith tradition,” effectively excluding others who are not part of a faith tradition, but who are capable of giving an invocation, which is nothing more than a petition for help or support. This provision makes clear that the city council is promoting religion over non-religion.

Since the adoption of this new invocation scheme in San Marcos and through February of this year, there were 37 invocations at regular City Council meetings. All but four of those prayers were directed to the Judeo-Christian God (at least two prayers were arguably addressed to some other deity, or a generic deity), and two of those invocations — both nonsectarian — were offered by a member and a minister, respectively, of the San Marcos Unitarian Universalist Fellowship.

Twenty-one of the prayers specifically invoked the name of Jesus, with phrases like “In the name of Jesus Christ our Lord and Savior,” “In Jesus’ name we pray,” “in Jesus’ precious name,” “in the name of Jesus as the Christ,” and similar phrases. One of the prayers included a recitation of “The Lord’s Prayer,” recognized as the prayer uttered by Jesus, according to some Gospel accounts. Many of the prayers were fawning and jingoistic, suggesting the righteousness of City Council members, the city, and the country.

At least 33 of the invocations given since the change in the invocation policy before the San Marcos City council were sectarian prayers — acts of religious worship to the Judeo-Christian God. They were done at a time when the chamber was full of citizens who came to participate in the governance of the city. Frequently, visitors and citizens in attendance when the prayers were introduced were directed to behave in a certain manner, e.g., stand and bow their heads, “pray with me,” “let us pray” — clearly religious practices.

Visitors and citizens in attendance were referred to in many of the prayers, if not all of them, as in the use of the inclusive “we” in reference to speaking to God for all in attendance. A new practice introduced by Mayor Daniel Guerrero this past February is to invite an elementary school child to lead those in attendance in the Pledge of Allegiance immediately after the prayer, subjecting the young child to the practice of government-sponsored prayer, something not allowed under the Constitution in our public schools.

The public broadcast of the prayers over the internet and cable television provides the City Council a way to religiously exhort those of its citizens who watch via those media. And the invocation is difficult to avoid if one wants to do so: The agenda is not followed in the order posted; or the actual time the prayer will be given cannot be determined except through guesswork, making it difficult to know when the invocation will be called for.

The invocation is never placed at the beginning of a meeting, but posted often as the fourth, fifth or sixth item, and may be done after a workshop, an executive session, public comments, and after proclamations are issued, so city council members, officials, administrators, and staff, as well as visitors present at the meeting, cannot easily avoid participation by being absent during the prayer.

One of the clergy who regularly offers prayers before the San Marcos City Council asserted before one of his invocations that “it can’t hurt to have a prayer.” On the contrary, the freedom of religion guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment necessarily carries with it the right to be free from religion imposed by the government, just as the freedom of speech does not permit the government to require me to speak, nor does the freedom of association require me to associate with those the government wants me to associate with.

When the government uses the religious practice of prayer while carrying out its civic functions, it compels all citizens who want to participate in our civic life or observe the government in action to partake of that religious exercise.

One of my favorite quotes about government sponsorship of religious practices is by the late Republican Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona:

Can any of us refute the wisdom of Madison and the other framers? Can anyone look at the carnage in Iran, the bloodshed in Northern Ireland or the bombs bursting in Lebanon and yet question the dangers of injecting religious issues into the affairs of state?… By maintaining the separation of church and state, the United States has avoided the intolerance which has so divided the rest of the world with religious wars. Throughout our two hundred plus years, public policy debate has focused on political and economic issues, on which there can be compromise…

Most of those who cooperate with city councils to promote prayer do so with noble intentions bereft of an appreciation of how their use of government to advance religion violates the rights of those who have different religious beliefs.

For instance, I do not believe that I should have to participate in another’s religious practice in order to participate in my government, but this is exactly what the San Marcos City Council compels me to do by its sanctioning of official prayer, mostly sectarian, at its meetings.

The early American patriot, abolitionist, and Baptist minister John Leland said,

[W]henever men fly to the law or sword to protect their system of religion and force it upon others, it is evident that they have something in their system that will not bear the light and stand upon the basis of truth.

Another early American patriot and author of “Religion and the Continental Congress, 1774-1789: Contributions to Original Intent,” wrote,

The framers [of the Constitution] sought to divorce religion from government… [T]o make religion dependent upon government was to depreciate true religion; to rely upon government to throw its weight behind religion was to declare God impotent to further his purposes through voluntary means.

While I am encouraged that a long line of American patriots and U.S. presidents from George Washington to Jimmy Carter appreciated the need to keep government out of religion, that history does me no good when no member of the San Marcos City Council will rise to the defense of our forebears and disapprove of government sponsorship of religion in our civic life.

As I have suggested before, one of the greatest ironies of this government prayer promotion is that the most prominent proponents of it are the Christian evangelicals, who believe most literally in the words of the Bible. None of them have ever explained publicly how their behavior can be reconciled with the teachings of Jesus to pray in secret and not in public where they can be seen by others as pious.

It is a feeble and flaccid religion that needs the imprimatur of government to find its relevance. If all who call themselves Christian followed the admonitions of Jesus, we would not have a problem with sectarian prayers at city council meetings throughout the United States.

[Lamar W. Hankins, a former San Marcos, Texas, city attorney, is also a columnist for the San Marcos Mercury. This article © Freethought San Marcos, Lamar W. Hankins. Read more articles by Lamar W. Hankins on The Rag Blog.]

great graphic!

Politics is the last refuge of the productively, and otherwise unemployable, incompetent. Religion is the last refuge of sons of blackhearted whores and a steadfast excuse for failure. Just ask Tom DeLay. Together they serve the useless quite well. For the politically religious I prefer the public stock and whipping post. But that approach is way to practical to be accepted today.