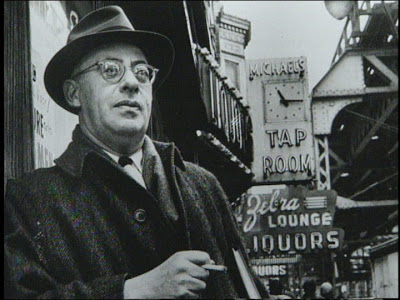

Saul Alinsky’s American values

‘The Radical… is that person to whom the common good is the greatest personal value. He is that person who genuinely and completely believes in mankind.’ — Saul Alinsky

By Lamar W. Hankins | The Rag Blog | January 30, 2012

These days, I don’t often think of Saul Alinsky, but now that Alinsky’s name has been used to slur President Obama in frequent speeches by self-promoting historian Newt Gingrich, it’s time to look at who Alinsky was and the values he stood for.

Gingrich obviously knows little about Alinsky, who died almost 40 years ago. Certainly, the only two things Barack Obama and Saul Alinsky have in common is that both lived in Chicago and Obama did some work as a community organizer, but he was hardly the sort of community organizer Alinsky was.

At recent campaign stops in Florida, Gingrich said,

We need somebody who is a conservative and who can stand up to him (Obama) and debate and who can clearly draw the contrast between the Declaration of Independence and the writings of Saul Alinsky… The centerpiece of this campaign, I believe, is American exceptionalism versus the radicalism of Saul Alinsky… President Obama believes in Saul Alinsky’s radicalism [and] a lot of strange ideas he learned at Columbia and Harvard.

Unfortunately, this is the exact opposite of reality.

In 1970, I was able to participate in a small community organizing training session in Austin conducted by Alinsky. Although I never worked full time as a community organizer, I found his ideas profoundly democratic, egalitarian, compassionate, realistic, and in keeping with every enlightened attitude expressed in this nation’s founding documents.

Without doubt, Alinsky saw himself as a radical, but not in the revolutionary or pejorative sense of that word. Alinsky wanted to get at the root of societal problems, not overturn our democratic system of government. In fact, Alinsky believed in and practiced democracy more fervently than any candidate now in the race for president.

Alinsky had the same vision and love of America found in Walt Whitman’s poetry. What Whitman was to poetry, Alinsky was to making democratic institutions serve the interests of the 99%. In the first chapter of his seminal book, Reveille for Radicals, published in 1945, Alinsky warmly identified with the diverse masses of the American people. He wrote that “During Jefferson’s lifetime the words Democrat and Radical were synonymous.”

Democrats and radicals were the few “who really liked people, loved people — all people,” no matter their race, ethnicity, religion — and were proud to be branded “radicals.”

They were the human torches setting aflame the hearts of men so that they passionately fought for the rights of their fellow men, all men… They fought for the right of men to govern themselves, for the right of men to walk erect as free men and not grovel before kings, for the Bill of Rights, for the abolition of slavery, for public education, and for everything decent and worth while. They loved men and fought for them. Their neighbor’s misery was their misery. They acted as they believed.

(Using the vernacular of the time, “men” meant humankind and was not intended to omit women.)

Alinsky identified America’s radicals as Patrick Henry, Sam Adams, Tom Paine, John Brown, Thaddeus Stevens, Horace Mann, Wendell Phillips,, Peter Cooper, Walt Whitman, Henry George, Edward Bellamy, John P. Altgeld, Henry D. Lloyd, Lincoln Steffans, Upton Sinclair, Bishop Bernard Sheil, and many others who stood with the masses of people fighting for the general welfare of all:

What is the American Radical? The Radical is that unique person who actually believes what he says. He is that person to whom the common good is the greatest personal value. He is that person who genuinely and completely believes in mankind. The Radical is so completely identified with mankind that he personally shares the pain, the injustices, and the suffering of all his fellow men. He completely understands and accepts to the last letter those immortal words of John Donne (that “no man is an island”)…

[The Radical] wants a world in which the worth of the individual is recognized. He wants the creation of a kind of society where all of man’s potentialities could be realized; a world where man could live in dignity, security, happiness and peace — a world based on a morality of mankind.

Alinsky dedicated his life to working for a society that would eradicate “all those evils which anchor mankind in the mire of war, fears, misery, and demoralization.” He fought for economic welfare; for the freedom of the mind; for political and social freedom; for “a high standard of food, housing and health” for all; for placing human rights “far above property rights”; for “universal, free public education,” which he saw “as fundamental to the democratic way of life”; for social planning that came from the bottom up, rather than from the top down.

Alinsky believed that jobs should be both economically rewarding and personally satisfying to the creative spirit, what he called “a job for the heart as well as the hand.”

Most of all, Alinsky fought against privilege and power “whether it be inherited or acquired by any small group, whether it be political or financial or [from] organized creed.” To Alinsky, the American Radical “will fight any concentration of power hostile to a broad, popular democracy, whether he finds it in financial circles or in politics.”

Alinsky disdained both conservatives and liberals. Liberals he saw as mostly hypocritical people who espoused his values, but did not live according to them. Liberals paralyze themselves into immobility by their inability to take a stand for political and economic justice based on true democracy. For Alinsky, it was essential to be partisan for the people; otherwise, for whom are you partisan?

Alinsky did not try to explain conservatives. He thought they were not worth explaining because they did not accept the American values he saw as essential for democracy. For Alinsky, only the Radical got it right: “The Radical does not sit frozen by cold objectivity. He sees injustice and strikes at it with hot passion. He is a man of decision and action.”

He described liberals as people who “fear power or its applications”:

They labor in confusion over the significance of power and fail to recognize that only through the achievement and constructive use of power can people better themselves. They talk glibly of a people lifting themselves by their own bootstraps but fail to realize that nothing can be lifted or moved except through power.

Now conservatives are the ones who talk this way.

Alinsky spent most of his life helping organize together the existing organizations in a community to find the power to change the lives of the people in that community. But during World War II, Alinsky’s disdain for fascism took him away from domestic organizing for a time. He described his war role in a Playboy Magazine interview shortly before his death:

I divided my time between a half-dozen slum communities we were organizing, but then we entered World War Two, and the menace of fascism was the overpowering issue at that point, so I felt Hitler’s defeat took temporary precedence over domestic issues. I worked on special assignment for the Treasury and Labor Departments; my job was to increase industrial production in conjunction with the C.I.O. [Congress of Industrial Organizations] and also to organize mass war-bond drives across the country.

It was relatively tame work for me, but I was consoled by the thought I was having some impact on the war effort, however small… The Assistant Secretary of State blocked [direct military service for me] because he felt I could make a better contribution in labor affairs, ensuring high production, resolving worker-management disputes, that sort of thing.

Alinsky’s first community organizing effort started with the Back of the Yards area of Chicago — the area where the meatpacking industry was located. My friend the late Paul Gorton Blanton, in his unpublished work The Outside Agitator, adapted from his doctoral dissertation, described the Back of the Yards area when Alinsky started organizing there in 1938:

Even for this late stage of the depression, unemployment was high. Street gangs ran wild. Racketeers were regarded by many as folk heroes. Police protection was rare. The filth of the neighborhood’s broken streets and alleys added to the environment of decay and despair. Garbage was commonly tossed into the alleys, and was later collected by a man with a shovel, a wagon, and a team of horses.

Neighborhood banks often failed during these depressed thirties, resulting in the loss of savings by many poor families. Mortgage foreclosures were frequent. Health care was grossly inadequate, particularly for children and the elderly. The inevitable cycles of poverty and disease brought about a neighborhood mood of hopelessness.

Alinsky organized disparate groups, even those who saw themselves as natural enemies, such as the C.I.O.’s Packinghouse Workers union and the Catholic Church, into an organization of organizations that identified the community’s most pressing problems and devised ways to eliminate them.

According to Blanton, “Clusters of families, groups, clubs, businesses, and economic enterprises, through which individuals in the community found their own identity” became, together, The Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council. Over several years, the Council took on and solved problems in health care, unemployment, education, nutrition, sanitation, fire safety, juvenile delinquency, and other matters.

The creation of a credit union that offered 1% loans drove most loan sharks and small finance companies out of the neighborhood. As a result of health services introduced by the Council, in just over one year infant mortality dropped from 10% to 1.5%, a free chest x-ray program was established to fight tuberculosis, a free dental program was developed, and water fluoridation was achieved.

Through other efforts, 2400 new jobs were created for neighborhood residents. Later, a free lunch program was created. Over the years, the Council lobbied successfully in both the Illinois state capital and before Congress for school-based food programs, including a free or reduced-price milk program that Congress instituted in 1955.

Part of Alinsky’s success was his brilliance at devising strategies and tactics that moved the power elites to respond to the demands of the people. He was able to analyze those in power and take advantage of their vulnerabilities, often by exposing their hypocrisy and corruption, and by using ridicule.

Once, when the first Mayor Daley who ran Chicago calculated that he could back out of some agreements he had made with another organization Alinsky had created in Chicago — The Woodlawn Organization (TWO) — Alinsky devised a strategy to embarrass Daley by creating havoc in Daley’s pride and joy — the O’Hare Airport.

Some TWO members researched the number of toilets and urinals at O’Hare and determined they could recruit 2,500 people to occupy all the toilets and line up four or five people at each urinal, and then rotate from urinal to urinal, making it impossible for most passengers just arriving at O’Hare to use a restroom.

When the word of this plan leaked to Daley, he had visions of vast numbers of travelers, desperate to relieve themselves, urinating in his pot plants at the airport. Daley capitulated instantly and TWO never again had problems with getting him to fulfill his promises to them.

Alinsky and his acolytes organized similar groups in many locations throughout the country. Their organizational efforts and tactics weren’t always successful, but most of them were.

Whatever Obama may have learned about organizing has not manifested itself in the partisan politics he has pursued since the time he worked in Chicago as a community organizer. Nothing in his manner or actions leads me to think that he is a follower of Saul Alinsky. Obama was still nine years old when Alinsky died. There is no evidence that he ever met Alinsky or was influenced by him.

I devoutly wish that Obama had Alinsky’s mindset, values, instinct, and creativity, and would use those characteristics against those who want the government to fail in its stated goal of securing the blessings of liberty for all the American people. But Obama has failed to be the sort of person I once thought he was. Still, there is no one else in the running for president who will come close to doing better.

Once again, Newt Gingrich has proven his ignorance about a historic figure that he claims to understand and about whom he likes to pontificate. Ironically, one group that is proving to be a strong supporter of both Gingrich and Ron Paul has also heaped praise on Alinsky. The Tea Partiers are studying Alinsky’s second book, Rules for Radicals, as they attempt to influence the political system to do their bidding.

They have had minimal success following Alinsky’s example, probably because they lack Alinsky’s aplomb and creativity, but mostly because they don’t share Alinsky’s values. This irony further exposes Gingrich as a faux historian who invents narratives to advance his political ambitions. He will never understand that Alinsky’s values can be traced directly back to the spirit of 1776.

[Lamar W. Hankins, a former San Marcos, Texas, city attorney, is also a columnist for the San Marcos Mercury. This article © Freethought San Marcos, Lamar W. Hankins. Read more articles by Lamar W. Hankins on The Rag Blog.]

I'll always remember him speaking at UT. 1965, or maybe 66. He was heckled for his stand on the civil rights movement. He asked the hecklers to stand up and he dressed them down. As I remember he got an ovation from the audience. The way he handled himself moves me to this day. A great man, one of my heroes.

Phil Sigmund