When government decides to kill:

The death penalty and the

question of actual innocence

[The Supreme] Court has never held that the Constitution forbids the execution of a convicted defendant who has had a full and fair trial but is later able to convince a habeas court that he is ‘actually’ innocent. — Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas

By Lamar W. Hankins / The Rag Blog / September 27, 2011

Almost every high school student and college graduate has thought about capital punishment. It is one of the most common topics to write about in political science, social science, English, and speech classes.

Everyone has an opinion and reasons to be for or against it. In this, I am not different from most other people. But my perspective about capital punishment has come to me over the 45-plus years I have been a participant in the functioning of the criminal justice system. I have learned that it does not function well at any level.

I have concluded that the criminal justice system is so imperfect and unreliable that it is irresponsible to assign it the authority to decide who should live and who should die. I didn’t always think this way. I used to respect the criminal justice system. When I was 20 years old, I spent the summer after my junior year in college working for the Texas prison system.

That summer, the Texas Department of Corrections (now the Texas Department of Criminal Justice) hired about 30 college students to introduce them to the prison system and to provide inexpensive employees to fill in while regular employees took vacations.

I learned that summer, from first-hand experiences, about wide-spread abuse of inmates. Four inmates that I was supervising were taken by prison officials — my immediate supervisor and the head of the prison shops — and beaten with ax handles for working too slowly. When I questioned the beatings, the assistant warden and then the warden told me that they had all fallen down the steps when they were taken away from their work area for about 30 minutes for a discussion about their slow work habits.

Even a naive 20-year old couldn’t accept that explanation after counting the dozens of individual knots that had suddenly appeared on their freshly shorn heads after that 30-minute discussion. The warden threatened me if I persisted in my complaint, and he moved me to other jobs that diminished my contact with inmates. But for the rest of the summer, after word of my complaint got around, I was told stories by inmates and guards about many abuses, including the drowning of inmates by prison officials.

That summer job was the beginning of the end for my unquestioning acceptance of official explanations for government misconduct. A few years later, when my younger brother was led into a marijuana buy by a snitch working off his own arrest for selling drugs by getting others to commit drug crimes so they could be arrested, I learned another lesson about how the criminal justice system functions. It was not enough to arrest people selling drugs; the government had to create the crimes so it could make more arrests.

When I became an attorney, I refused to represent defendants who had become snitches. Partly it was for self-preservation. How could I trust that a client setting up drug cases for law enforcement would not try to set me up? It would be a coup to get a criminal defense attorney arrested. It would not matter that I neither used nor sold illegal drugs. At the very least, I would be tainted for life just for having such an allegation made against me, and I could have lost my license to practice law.

Shortly before I became an attorney — and just after the Supreme Court in 1976 allowed the resumption of capital murder cases after a four-year moratorium while it sorted out some death penalty issues — I was a legal assistant for one of the premier criminal defense attorneys in Houston. He had been appointed to represent a notorious defendant accused of capital murder and other crimes.

The capital murder trial lasted two months. The jury could not reach a decision on punishment. At that time, the law in Texas required that if the jury could not reach a decision on punishment, the entire trial had to be done over. A few months later, we appeared back in the same courtroom for the re-trial. The prosecutor offered a deal on nine charges against the defendant. He received three life sentences and six 99-year sentences, thus avoiding a death sentence.

In 1979, while practicing in Bryan, I was appointed to represent a defendant in another capital murder case. While my client had not actually done the killing, he had participated in actions that led to the death of an innocent man whose truck my client and his cohorts wanted to steal. In Texas, a concept known as “the law of parties” made him equally culpable.

The trial lasted for three months. My client was convicted and sentenced to death, but the case was overturned on appeal because the judge had not allowed me to fully cross-examine a key witness against him. That decision came several years after the first trial. By then, I had moved to San Marcos and other attorneys were appointed to represent the defendant when his case was set for re-trial.

During the first trial, we were allowed to introduce what was termed “mitigating evidence” — evidence that might show why the defendant should not receive the death penalty — but the judge did not explain to the jurors how they should consider and apply that mitigating evidence. That evidence included information that the defendant had voluntarily surrendered to the sheriff by turning himself in at the jail, that he was borderline mentally retarded, that he had grown up in dismal poverty, that he had not before committed a violent crime, and that he was subjected to extreme brutality by his father during his formative years.

I had access to all of that mitigating evidence and was a witness to his surrender to the sheriff. I had located the defendant (I was previously appointed to represent him on a misdemeanor charge) and drove him to the jail the night he turned himself in. I contacted the new defense attorneys and offered to help in any way I could, including being available to testify about his voluntary surrender to the sheriff.

The new attorneys presented no evidence of these mitigating circumstances at the re-trial, even though a newer court opinion had given judges specific instructions about how to explain such mitigating evidence to jurors so that it could be applied fairly by them in their deliberations about whether the defendant should be given a death sentence or a life sentence.

He was again sentenced to death. That punishment was carried out 22 years after the crime had been committed. His death did yield one positive benefit — he donated his body to the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston to further the education of those studying to become doctors.

After contacting some of the jurors from the original trial, I had learned that if they had been instructed how to consider and apply the mitigating evidence, they would have voted to give my client a life sentence. In the second trial, no mitigating evidence was presented, even though jurors would have been instructed how to consider and apply it.

As a result, the second set of jurors had no evidence to consider in deciding my former client’s fate. At the time of his death, a habeas corpus petition was pending before the court charging that the attorneys in his second trial had provided less than effective representation by failing to present the mitigating evidence that might have saved his life.

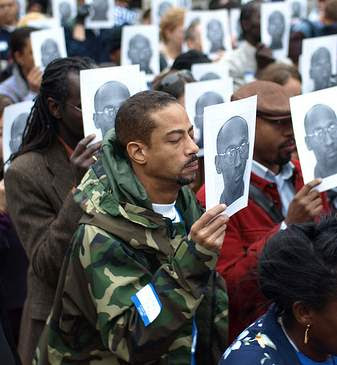

The recent execution of Troy Davis in Georgia after seven of nine witnesses recanted their testimony or admitted that they had lied at his trial brings up other issues of manifest unfairness in the criminal justice system. Troy Davis was convicted of murdering an off-duty police officer and sentenced to death.

In addition to the witness recantations, new evidence suggests that Davis had been inside a nearby pool hall and was part of a crowd that left the pool hall in response to a commotion in the adjacent parking lot where a homeless man was being beaten by a man named Coles, who is believed by many to be the killer of the off-duty officer who came to the homeless man’s aid.

The recanting of false testimony or mistaken eyewitness identification is not unusual, especially when the testimony is stimulated by over-zealous investigators intent on a conviction based largely on their gut instincts or dislike of a defendant. Psychologists have known for at least 50 years that eyewitness testimony is the most unreliable evidence presented in most criminal cases. But the courts in most jurisdictions have not allowed scientific evidence about the unreliability of eyewitness identification to be presented to jurors. That has begun to change.

A primary reason for the change has come from the work of the Innocence Project, which started in 1992 at the Benjamin Cardoza School of Law. When DNA testing became available to analyze blood from a crime scene, it became possible to determine whether a particular accused person could have been the culprit.

Before the early 1990s, many defendants were convicted on eyewitness identification and circumstantial evidence, such as a match between the blood type of an assailant and blood found on the victim, which did not rule out the possible guilt of millions of others with the same blood type as the defendant. The Innocence Project started looking back at some of these old cases where there was blood evidence that had never been subjected to DNA analysis.

Resulting from the use of DNA analysis, 70% of the cases that the Innocence Project has taken back to court have resulted in wrongful convictions because of faulty eyewitness identification of the assailant, usually in cases of murder or sexual assault.

In other cases, faulty scientific analysis of forensic evidence by government laboratories and investigators has resulted in wrongful convictions. The Willingham arson case is one example. The arson investigators misunderstood the forensic evidence and implicated Willingham in the deaths of his three children. He was executed in 2004.

In the early 1990s, a pathologist in west Texas, Ralph Erdmann, is believed to have faked about 100 autopsies and falsified an unknown number of toxicology reports, many of which resulted in wrongful convictions. Erdmann was convicted on several counts of evidence tampering and perjury after defense attorneys and others sparked an investigation into his forensic practices, but it took the appointment of a special prosecutor to uncover most of his misdeeds.

Prosecutors have enormous discretion about whether to charge a defendant with capital murder. The same year that my client in Bryan was charged with capital murder, at least five other cases in the same county could have been prosecuted as capital cases, but were not.

They were murders committed during the commission of kidnapping, burglary, robbery, aggravated sexual assault, or arson. The prosecutor decided, for his own reasons, that the capital murders committed by these defendants did not need to be prosecuted as capital cases. What made my client’s case special was that four black defendants killed a white man. In the other five cases that year, the victims were all black.

The race of the victim and the race of the defendant was the only salient difference in the six cases. (Occasionally, however, a white person does receive the death penalty for killing a black person, as in the horrendous dragging death and decapitation of James Byrd in East Texas a few years ago.)

For many defendants wrongfully convicted, there are no adequate remedies at law. Many federal judges and some Supreme Court Justices believe the Constitution does not require reconsideration of cases that have been fully litigated even when there is evidence that the defendant is actually innocent of the crime charged.

Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas wrote in 2009:

This Court has never held that the Constitution forbids the execution of a convicted defendant who has had a full and fair trial but is later able to convince a habeas court that he is “actually” innocent. Quite to the contrary, we have repeatedly left that question unresolved, while expressing considerable doubt that any claim based on alleged “actual innocence” is constitutionally cognizable.

As journalist Ed Brayton explained this point further in 2010:

[T]he 9th Circuit Court of Appeals has decided that the fact that a convicted criminal can now be proven to be innocent does not matter if he filed an appeal in 16 months rather than the 12 months allowed by the statute of limitations. Actual innocence simply does not matter, only technicalities do.

Criminal and appellate procedures, such as deadlines for filing appeals and the rules for how and when to file writs of habeas corpus challenging wrongful incarcerations, are more important in our criminal justice system than proof of the actual innocence of people in our prisons and on our death rows.

These and many similar reasons, including my own experiences as an attorney with faulty eyewitness testimony, have led me to conclude that the criminal justice system is too riven with mistakes to be allowed to put anyone to death. At least a million Texas property owners each year don’t trust the government to decide accurately the value of their property. With so little confidence in government, why would we give that same government the power of life and death over a human being?

Law professor Paul Campos of the University of Colorado at Boulder summed up the Scalia and Thomas position, which is basically the position of the criminal justice system as a whole, in reference to the Troy Davis case:

The defense in this case is claiming that there’s something unusual about Troy Davis’ situation, requiring extraordinary action on the part of the Supreme Court. But there’s nothing unusual about his situation. The American legal system routinely sentences people to long prison terms and even to death on the basis of dubious evidence, in trials featuring overburdened, underfunded, and marginally competent defense lawyers. Obviously under such conditions mistakes are going to be made. If such mistakes make verdicts unconstitutional, then the whole system is unconstitutional.

And that’s a difficult proposition to accept for most people in the land of the free and the home of the brave. But it leads to an inevitable question of morality: “Is this justice?”

[Lamar W. Hankins, a former San Marcos, Texas, city attorney, is also a columnist for the San Marcos Mercury. This article © Freethought San Marcos, Lamar W. Hankins. Read more articles by Lamar W. Hankins on The Rag Blog.]

Thanks for the good material — I placed it on my facebook.