Pictures at an execution:

Texas hits the 500 mark

I felt like a player without a team, an interloper, an uninvited party guest. Nothing felt portentous or grave, just awkward.

By Laura Lark | The Rag Blog | July 8, 2013

See gallery of photos by Otis Ike, Below.

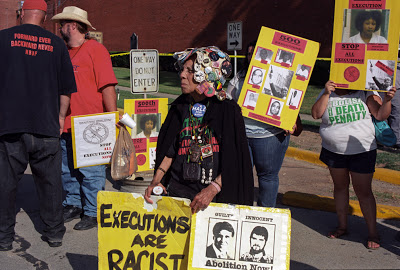

HUNTSVILLE, Texas — It seems that Kimberly McCarthy’s execution by lethal injection at Huntsville State Penitentiary should have been a more, well, special occasion. It was, after all, a record-breaking 500th execution in the state of Texas, and McCarthy’s credentials: female, African-American, the ex-wife of a Black Panther — lent the affair everything it needed for a truly charged and politicized scene.

Patrick Bresnan and I, both residents of nearby Houston, expected something extreme. Maybe sinister. Violent. Redemptive.

It was, rather, despite the presence of a few megaphone-wielding Panthers decrying white devils, Rick Perry, in particular, the protesting on the anti-death penalty side was pretty lackluster.

The five women on the pro-death penalty side weren’t much more interesting, either, and it was an odd mix: a biracial lesbian couple from Houston, the wife of a corrections officer, her mother-in-law, and her little girl.

“It’s her second execution,” the woman beamed, bouncing her fat, pink-and-white-frocked child on one hip.

The kid was two and probably ready for a nap. I nodded, looking back and forth from one self-satisfied face to the next.

I felt like a player without a team, an interloper, an uninvited party guest. Nothing felt portentous or grave, just awkward. Walking back and forth from one side to the other, I had my photo taken near the “Be a corrections officer!” recruitment sign a few times.

It seemed fitting.

Perhaps it was the hundred degree heat and stifling humidity; perhaps, post-Occupy Wall Street, demonstrators understand how truly futile efforts are against the system. Whatever the case, neither side demonstrated much energy. It all came off as practical, perfunctory.

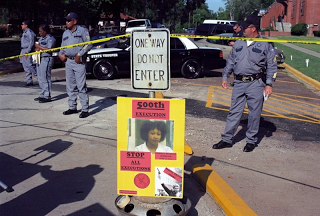

It didn’t matter whether people were pleading for forgiveness or demanding an eye for an eye, even the angriest and most passionate did nothing to provoke the line of stern, Stetson-sporting armed officers on the other side of the tape.

Relatively peaceful protesting never appeared more resigned, rote, or pointless.

It wasn’t much of a show. And then it was over: Kimberly McCarthy was declared dead.

Even the following scene — one that should have been shocking and cinematic — in which a chubby guy in a white button shirt, a tie designed to look like a Texas state flag, and a pair of dark shades, following the announcement of McCarthy’s passing, strode from officer to officer and gave each a firm, congratulatory handshake.

A big high-five.

Even holding hands with the most vocal of the protestors and praying didn’t change much for me. I recall looking at all of the faces of the angry and sorrowful and horrified and feeling as if nothing, anywhere, had or would ever change. As always in these situations, I felt lazy, ineffectual, and impotent. I walked away feeling as if I’d eaten dirt.

Immediately afterwards, Patrick Bresnan and I, along with the penitentiary chaplain and three associated with the deceased, arrived at the funeral home to view McCarthy’s body. One of the women, a relative, recognized me from earlier that afternoon.

“Please,” she said, leading Patrick and me to the body, “Touch her.” Noticing my reticence, she took my hand. “Please. She didn’t touch hardly anybody for the whole time she was on death row. She would have wanted to be touched.”

The woman guided my hand over the dead woman’s face and head. I looked at her grayish, lifeless face — something neither good nor evil. Just dead.

The chaplain smiled, telling us that she left at peace with herself and the world. That her final words were, “God is good.”

With my hand to the ashen cheek of Kimberly McCarthy, I felt shame and pain and sorrow and loss throughout my entire body. For the first time that day, the waste of a human life and the lost possibility of redemption truly overwhelmed me. I found myself unable to stop crying.

I sobbed as Patrick led me to his car.

And then, again, it was over, and we drove home.

[Laura Lark is an award-winning visual artist and a widely-published writer. She has an MFA in Painting and an M.A. in Creative Writing/Literature, both from the University of Houston.Otis Ike, aka Patrick Bresnan, is a widely-exhibited photographer, a documentary filmmaker, an affordable housing activist, and a builder. He holds a masters degree in Sustainable Design from the School of Architecture at the University of Texas .]