The Beat Generation in the rearview mirror

By A.G. Mojtabai / July 11, 2008

Even from a distance, it was easy to guess that the clerk with the bowed head at BookPeople was reading behind the counter. Face to face, she was eager to share the title: Poetry As Insurgent Art by Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Had I seen the Ransom exhibit on the Beats? she asked. Wasn’t it “awesome?”

A chorus of “awesome … simply awesome” greeted me from the visitors book at the entrance to the Ransom exhibit, but also a scattering of distinctly dissonant notes (on behalf of the Beats’ abandoned wives and children), along with a murmur of bemused bewilderment: “Yes … But is it Art?” and “Funny

My own feeling turned out to be a mix of all of the above, although proportioned differently and differently named. People of my generation use “awesome” sparingly, if at all, the word reserved to signify epic magnitudes or profoundest depths—not what we find here. Such an inflation of message and response strikes me as typical of the Beat phenomenon, though.

“On the Road with the Beats” has been on exhibit at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas in Austin since February and will continue to August 3. The scroll manuscript of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, on loan from March until June 1, will have departed by the time of this printing. The occasion for the exhibit is the recently celebrated 50th anniversary of the publication of On the Road.

“A generation in motion” is the exhibit’s organizing theme. According to the brochure:

“Pilgrims in search of a destination, [the Beats] crisscrossed the globe, from New York to San Francisco, Los Angeles to Mexico City, Tangier to Paris, Calcutta to London. … Motion, improvisation, and process are driving concepts … Experimental jazz and bebop prompted writers to stretch prose and the poetic line to rhythmic extremes. … The painters known as the New York School inspired influential collaborative projects.”

Originally a junkie term, “Beat” meant many things: desperate, wasted, down-and-out (beaten-down)—to which Kerouac added “beatific,” which he defined as being subject to bursts of “ragged and ecstatic joy.” To most people, mention of the Beats conjures up the small founding group of friends: Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, Neal Cassady (better known as the fictional Dean Moriarty in On the Road), and Allen Ginsberg.

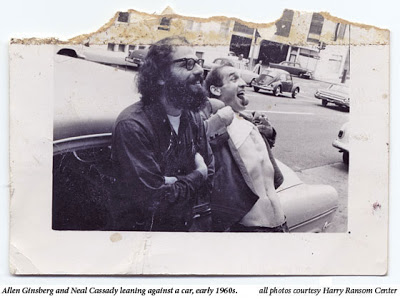

Much on the model of Ezra Pound’s relationship with the early modernist writers, Ginsberg served as editor, literary agent, and promoter for his friends. Ginsberg’s letters provide a guiding thread through their lives and the exhibit. The far fewer letters of Cassady are no less valuable. As love-focus and muse for both Kerouac and Ginsberg, Cassady was a pivotal figure in the movement. His letters were the inspiration for what Kerouac called “bop prosody”—his signature extemporaneous style.

Nowhere is the Beats’ self-mythologizing more blatant than in their depictions of Cassady. For Kerouac, his friend’s energies were beyond the natural, his countless transgressions proof of his superabundant life, “everything about him larger than life,” Kerouac wrote in one of his journals, published in Road Novels 1957-1960. Through Kerouac’s eyes, Cassady became saint, angel, archangel, “the holy con-man with the shining mind. … the Holy Goof.” When Cassady stole a tankful of gas they needed to move on, it was a theft “that saved us, a divine theft … Prometheus at least,” according to Kerouac’s journal entry. And, as Kerouac confessed, he always “shambled after [Cassady] as I’ve been doing all my life after people who interest me, because the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time.”

Ginsberg added to this aggrandizement: “I have finally taught Neal,” Ginsberg wrote, “that he can do anything he wants, become mayor of Denver, marry a millionaire or become the greatest poet since Rimbaud. But he keeps rushing out to see the midget auto races.”

Cassady, however, was not unanimously liked or trusted by the other Beats. Having graduated from reform school into the streets, he was a consummate con-man, hustler, druggie, drunk, car thief (but only for joy rides and “kicks”), petty thief, and a sometimes-violent, indefatigable sexual adventurer with both men and women. Abandoned by his alcoholic father as a youngster, he had a sad start in life. On the Road repeatedly reminds the reader that the narrative is an account of the search for Neal’s lost father—a would-be archetypal quest for “the father we never found.” In point of fact, it does not seem that they searched very hard. Perhaps the father did not want to be fou

I visited the Ransom exhibit in April. Upon entering, I was immediately confronted with Kerouac’s famous scroll manuscript of On the Road lying in state. It was an attention-grabber—“This is the longest book I have ever seen,” in the words of an awed fifth-grader—and a visually arresting artifact in an exhibit that skillfully blends textual, visual, and aural elements. Sepia-toned and crumbling, venerable in its decrepitude and in the care expended on its preservation, it reminded more than one visitor of one of those ancient Dead Sea Scrolls.

A continuous stream of paper nearly 120 feet in length (the first 48 feet are unfurled in the Ransom display), the scroll was formed by taping pieces of tracing paper together. The idea was to facilitate continuous motion on the part of the writer. Typed at white heat speed during three weeks in 1951, the scroll offered Kerouac (stoked on massive doses of caffeine) a way to get the story out with maximum speed and without overmuch reflection. The tail end of the scroll manuscript was allegedly eaten by a friend’s dog, but it is possible that the scroll lacked an ending at the time. There was a long trek yet to come: The book as we know it took more than 10 years, counting Kerouac’s note-taking before hitting upon the scroll method, and six years of revision afterward as he struggled to get it published.

The scroll is a nonfictional account of five road trips taken by Kerouac with Cassady from 1947 to 1951. Real names are used. In the finally published novel, names are changed, sexual exploits are toned down, and some self-conscious flourishes are added.

“First thought, best thought” was Kerouac’s credo in creating the scroll. To which the answer must be: Well, sometimes …

And sometimes not. I have trudged through the scroll, word after word, in a recently published book transcription. Although writing nonstop must have been a liberating breakthrough for the author, it presented a rather different experience for this reader. All five books, five journeys, are jammed together into a seemingly interminable single paragraph. Far from suggesting an open road or flowing river, the scroll creates a clotted, even static, feeling—a sense of congealed motion. Free of later embellishment for literary effect, some passages in the raw scroll version are stronger than in the final book version, though.

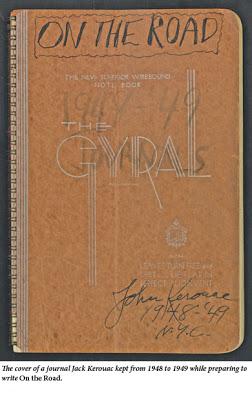

The most interesting artifact in the exhibit, to my mind, is a cheap, lined, spiral-bound notebook, one of Kerouac’s travel journals from 1949. It had been sold for $1,000 to a rare book dealer by the Beat poet Gregory Corso, who needed the money for heroin. The notebook can be leafed through in digital facsimile. What caught my eye were the intense reading lists, and a prayer for good times and bad, composed by Kerouac (a cradle Catholic) upon learning that his first book, The Town and the City, had been accepted for publication. The last page is filled with lists of crops for a farm Kerouac hoped to start up with Cassady, thinking it would provide a source of steady income and a healthful way of life.

On the whole, the exhibit struck me as long on literary developments arising from the Beat movement and wide in its exploration of outreach to other arts, but short on backstory. The Beats did not spring unaided from the ear of Zeus. True enough, as the Ransom’s narrative has it, the Beat movement was reactive to the repressive conformism and complacency of Cold War America. But it was also, and as truly, a continuation of long-standing American tradition. In the case of On the Road, arguably the iconic document of the Beat movement, the continuities are glaring. The open road, and before that the open frontier, had long been part of the American romance. The expansive thrust into unknown territory, adventure, the camaraderie of the open road, were—and are—cherished features of our nation’s traditional vision of itself.

The ancestors of On the Road are legion: Walt Whitman wrote the enabling charter. Twain sent Huck and Jim on a raft down a watery road. Melville had Ishmael and Queequeg light out for the open sea. Emerson counseled self-reliance; Thoreau, marching to a different drummer. And there is the long tradition of the picaresque in world literature.

From Beat to Beatnik to Hippie to Punk. Although the Beats are often conflated with the later hippies and thought of as political, they tended to be apolitical in the ’40s and ’50s. (During the ’60s, the activism of Ginsberg and others made for a somewhat different story.) Far from engaging the world, and despite all their world travel, the Beats remained largely clueless—not simply incurious and insensitive, but insensible: blind to the variety and complexity of lives other than their own. In an instant judgment that was really a prejudgment, Kerouac saw, and admired, Mexicans as “Fellahin … the essential strain of the basic primitive,” brown toilers in the brown earth, “pure and ancient” earth figures, with “slanted eyes and soft ways.”

Even Mexico City was “one vast Bohemian camp. … This was the great and final wild uninhibited Fellahin-childlike city that we knew we would find at the end of the road.”

In a missive to Cassady in 1957, Kerouac wrote of the locals in Tangier: “They are all hi, all wild, hep, cool, great kids, they talk like spitting from inside the throat Arabic arguments.”

This is sheer projection, of course, sweeping generalization that all but obliterates the individuals standing before him, professed admiration bordering on contempt.

A similar incomprehension is found in the Beats’ treatment of women. Women are perks of the road, ripe for the picking, thrilling for the moment, but afterward all too often bitter or clinging. Marriages are contracted, children conceived, and the boys in the club are off to their next great adventure. Escape from the complexities and responsibilities of the adult world, as much as anything else, seems to be the animating force of On the Road. Here are a few of many tip-offs: “Bitterness, recrimination, advice, morality, sadness, it was all behind him…” “Goodbye, goodbye. We roared off…” “Nothing behind, everything ahead…” To which Cassady characteristically added: “Wow! Damn! Whoopee! … Less go, lessgo!”

At one point, even Burroughs was moved to write Ginsberg and explain why he had advised Kerouac against leaving on another jaunt with Cassady. His letter is cited in Jack Kerouac’s American Journey:

“Obviously the ‘purpose’ of the trip is carefully selected to symbolize the basic fact of purposelessness. … To cross the continent for the purpose of transporting Jack to Frisco where he intends to remain for 3 days before starting back to N.Y. [is] a voyage which for sheer compulsive pointlessness compares favorably with the mass migrations of the Mayans … [a] voyage into pure, abstract, meaningless motion …”

Kerouac had a dream, and it surfaced from time to time, of having a home and a stable marriage. “I want to marry a girl,” he wrote, “so I can rest my soul with her till we both get old. This can’t go on all the time … all the franticness and jumping around.” Instead, his marriages quickly dissolved, and he returned repeatedly to his mother’s house (which he disguised as his “aunt’s” house in his fiction). This was the only home he would ever know. He died in 1968 at age 47 from complications of alcoholism. By the late ’60s, the original friends had drifted apart, and Kerouac had dissociated himself from many of his followers.

The social norms that had so constricted the Beats had already begun to change in the ’50s in the aftermath of the Kinsey Reports. The novel Peyton Place was published and reviewed at pretty much the same time as On the Road. The doors to the counterculture had been opened.

The Beats were the heralds of change, though, and loud about it, refusing to lead Thoreau’s “lives of quiet desperation” or, in Kerouac’s words, to “go mad in recognized sanity.”

A Ransom visitor signed “Lady Mariposa” wrote this tribute to Kerouac: “Because of you I can be… Besos, mi Jack.” Today, in large measure because of the Beats, homoerotic love dares to speak its name. Along with all the writers who come after them, I am indebted to the Beats for their invigoration of the arts, for shattering the molds and enlarging the realm of what can be printed, sung, painted, and said. There has been a progression since then, however. Think of gangsta rap, of Bret Easton Ellis and the “brat-pack” writers of the late ’80s and the ’90s; think of Andres Serrano’s crucifix submerged in urine. “Transgression,” sometimes billed as the obligation of a true artist in the contemporary world, has become so widespread and predictable that it seems almost tame—trendy transgressive, if you will.

There is a muted undercurrent running through Kerouac’s writing. It is discernible in the travel notebook of 1949, where he recorded his plans for buying a farm and growing “sturdy” as well as “seasonal” crops, and in his recurrent daydream of finding the right girl, settling down, and resting his soul. It becomes impossible to ignore in the coda to On the Road, a passage so poignant and lyrical that it seems more sung than said:

So in America when the sun goes down and I sit on the old broken-down river pier watching the long, long skies over New Jersey and sense all that raw land that rolls in one unbelievable huge bulge over to the West Coast, and all that road going, all the people dreaming in the immensity of it … the evening star must be drooping and shedding her sparkler dims on the prairie, which is just before the coming of complete night that blesses the earth, darkens all rivers, cups the peaks, and folds the final shore in, and nobody, nobody knows what’s going to happen besides the forlorn rags of growing old, I think of Dean Moriarty, I even think of old Dean Moriarty, the father we never found, I think of Dean Moriarty.

Blesses … darkens … cups … and folds in. The prose slows down. After all that frantic rushing around, all that road going, the completion of Kerouac’s journey comes at a broken-down pier in Hoboken, near where he first set out, where he offers up this hymn to night, friendship, remembrance, and rest.

A.G. Mojtabai is the author of nine books, including the new All That Road Going. She lives in Amarillo.

Source. / The Texas Observer

The Rag Blog