The story of the Thirteenth Floor Elevators – Austin’s favorite psychedelic sons – is rich, rowdy and textured. They sparked a counterculture, birthed a sound and inspired a generation of musicians. In fact, their work and their legend continue to serve as inspiration to new artists and to a legion of cult followers.

By Thorne Dreyer / The Rag Blog / February 21, 2009

See ‘A Long, Strange Trip: An originator of acid rock in the ’60s, Tommy Hall used LSD to expand his consciousness. He’s still psychedelic,’ by Jennifer Maerz, Below.

The story of the Thirteenth Floor Elevators – Austin’s favorite psychedelic sons – is rich, rowdy and textured. They sparked a counterculture, birthed a sound and inspired a generation of musicians. In fact, their work and their legend continue to serve as inspiration to new artists and to a legion of cult followers.

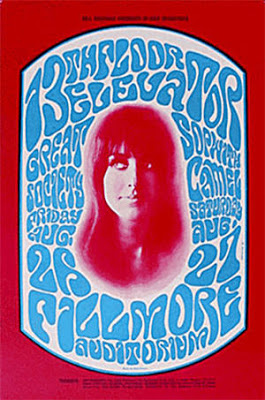

The Elevators joined a gang of Austin carpetbaggers – including promoter Chet Helms, musicians Janis Joplin and Powell St. John and the rowdies from Rip Off Press – who played a formative role in the Sixties San Francisco music and counterculture scene. The Elevators headlined the Avalon and Fillmore Ballrooms, the palaces of Sixties rock.

I first saw the Thirteenth Floor Elevators at Jubilee Hall in Houston in the mid Sixties. It was an extraordinary and totally consuming experience. Their live performances are truly a thing of legend.

The Rag Blog reported last year on the death of original Elevators bass player Benny Thurman. And of course the tall but so very true tale of Elevators front man Roky Erickson — his vision, his unforgettable voice and the well-documented battles with his demons — has been told far and wide. (The other prime mover, guitar player Stacy Sutherland, contributed — in the words of S F Weekly’s Jennifer Maerz — the band’s “acid-drenched garage-blues style.”)

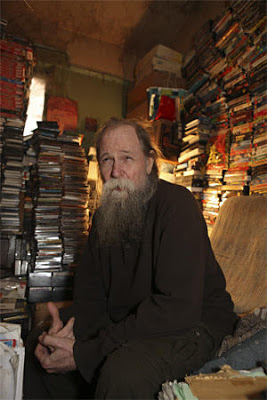

Less known is the story of stoned poet Tommy Hall from Houston who introduced acid to the band and the electric jug to the world. The Rag Blog’s Gerry Storm wrote of Tommy Hall: “He was called ‘Turn On Tommy.’ He was a fast talker, a hustler, a jive artist, a rapper, a believer, a fanatic, a salesman, and sometimes a bore.”

The following is a fascinating feature on Tommy Hall, from the Feb. 17, 2009. S F Weekly. Hall now lives in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district where he is still stoned and still creating.

A Long, Strange Trip: An originator of acid rock in the ’60s, Tommy Hall used LSD to expand his consciousness. He’s still psychedelic.

By Jennifer Maerz / February 18, 2009

Tommy Hall is nursing a Coke at a corner table at the Hemlock Tavern, a Polk Street music dive. The guru of ’60s psychedelic rock doesn’t drink alcohol. Booze brings you down, and Hall believes you should always be working on a high.

The jukebox is playing “You’re Gonna Miss Me,” the biggest hit by Hall’s band, the 13th Floor Elevators. The 1966 single made it onto the soundtrack of the film High Fidelity and the prized garage-rock box set Nuggets, helping the group gain massive cred with young garage-rock fiends.

The Elevators’ jug player, philosopher, and lifetime LSD devotee either pretends not to notice his song or genuinely can’t hear it over the din of early arrivers for the club’s headliners, Mammatus. The metal band is one of many local artists whose stoned sound has ancestral ties to Hall’s sonic ideology.

For many of his 66 years, Hall has been pursuing intellectual enlightenment through acid. He began that quest in the mid-’60s with the 13th Floor Elevators. Music scholars now note that the Elevators pushed an aggressive psychedelia that stood out against the feel-good artists of the time, pre-dating both punk and new wave. The band combined lingering, futuristic garage-rock jams with propulsive rock ‘n’ roll rhythms, grooving well with the counterculture’s burgeoning drug experimentation.

Three elements made the Elevators truly transcendent: singer Roky Erickson’s manic, mercurial vocals; Hall’s invention of the electric jug — which made inexplicably cool sound effects based on the reverberations of his voice; and Hall’s beautiful, image-rich lyricism promoting the spirituality of getting high. Of the last, he says now that he was combating the teenybopper attitude prevalent during the British Invasion. “We were trying to get into the results of acid,” he says, “to get into the results of the universe.”

Four decades after the Elevators collapsed, experimental garage rock and metal have enjoyed a huge resurgence in the Bay Area, and many of the leading acts have been influenced by Hall’s band: droning rockers Wooden Shjips, garage punks Thee Oh Sees and Ty Segall, and pop songwriter Kelley Stoltz, to name a few. The Elevators’ cult following is far from regional: Danger Mouse, the producer behind Gnarls Barkley and Beck, told The New York Times that he greatly admired the Elevators’ mix of common melodies and left-field sonic adventures.

When he was playing with the Elevators, Hall made it a rule to drop acid every time someone picked up an instrument. From all reports, he didn’t stop dosing regularly until very recently, when he lost his LSD connection and had to stick with pot. Hall says he’s holding a bag of mushrooms at his apartment, a one-room efficiency in a sketchy Tenderloin residential hotel. He’s saving that stash for the final breakthrough on his current project, a book revealing divine patterns in the solar system he’s been working out in his head for years.

Hall still has very clear ideas about what makes a band psychedelic. That’s why he’s at the Hemlock to see Mammatus, an underground band he first heard at Amoeba Music, and one he believes is carrying on the tradition of trip music. These musicians “flash” to a higher consciousness, he says, darting a chalky hand across his scraggly Merlin beard. “It’s real music,” he adds. “The rest is just a bunch of noise.”

Hall’s offbeat observations about music make him an engrossing conversationalist. He intellectualizes songwriting to levels far beyond the average musician, and gives almost holy meaning to his favorite artists. But he also unleashes a torrent of information independent of whoever is on the listening end, the result of years of sustained drug use. Talking with him is like flipping on multiple public affairs programs midway through the discussion. It’s challenging to comprehend everything he’s saying. Pay attention, though, and you can sort salient points and philosophical nuggets from the sometimes intolerant — and occasionally racist — ramblings.

With a ravenous appetite for higher learning, Hall could have been a flawed yet significant cultural signpost, a rock ‘n’ roll Timothy Leary. Instead his lifestyle teeters closer to another visionary rock ‘n’ roll drug casualty, Pink Floyd’s Syd Barrett.

Despite his struggles, however, Hall is still a fascinating figure in musical history. It’s not often that you encounter someone who so fiercely believes rock ‘n’ roll is a voyage to the beyond. But it’s been a difficult journey, one that isn’t without its casualties.

“Most bands are just in it for entertainment,” music industry vet and Elevators fan Bill Bentley says, “but the Elevators gambled on it with their lives and they got squashed.

If the Great American Music Hall has the equivalent of a VIP section, Tommy Hall is perched in it, a plaid flannel shirt hanging on his hunched frame. It’s the day after Halloween, and Roky Erickson is the headliner.

Erickson’s career as a solo artist was given new life with the 2005 documentary You’re Gonna Miss Me, which propelled the Elevators back into public discourse while showing the damage caused by methodical drug use. Erickson was the group’s most serious victim, and his communication skills are delicate these days. Nonetheless, he’s a cause célèbre in certain rock circles and has sold out the Great American tonight — in part because this performance promises to be a historic one. Erickson’s set list will include 13th Floor Elevators songs, which he hasn’t played live since the late ’60s, when he started forgetting his lyrics onstage and wearing a Band-Aid over the “third eye” on his forehead.

Upstairs, Hall sits incognito near the soundman, flanked by his closest friends, husband and wife George Ripley and Priscilla Lee, who are wearing their 13th Floor Elevators shirts for the occasion.

Ripley warned earlier that Hall had refused to perform tonight. The Elevators’ wordsmith, who invented the electric jug’s spectra effects, is strangely dismissive these days about his role in the group. Hall says it was his limited abilities on a musical instrument that forced him to put everything into the Elevators’ lyrics and ideology. “I was mainly trying to advance a philosophy so I could take over the whole acid thing,” he says. “The jug occupied a position.”

A young Austin band called the Black Angels opens the show with Velvet Underground–aping rock. This same group will double as Erickson’s backing band; singer Alex Maas has learned the electric jug in preparation. After hearing them perform, Hall believes the Black Angels aren’t playing with enough “higher structures.” He’ll later tell the group that there are other psych bands ahead of them, recommending Mammatus, “so they’ll learn.”

When the Texans come onstage for the second time, Erickson is at the mike. The portly singer opens with his ghoul oeuvre — goofy songs about vampires and zombies — before turning toward the Elevators with “You’re Gonna Miss Me.” When he howls, “How could you say you missed my lovin’, when you never needed it?” he sounds equally maniacal and naked. His voice remains a powerful weapon.

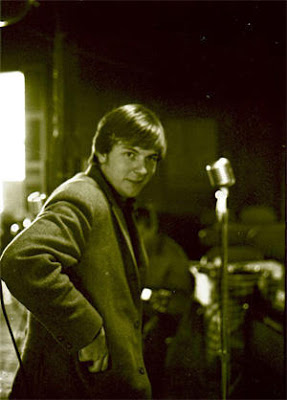

Erickson had already written “You’re Gonna Miss Me” when Hall discovered him in 1965, sparking the idea for the first — and only — band Hall put together. The pair quickly formed a bond and traveled into deep hallucinatory space, setting Hall up as a psychotropic prophet on a vision quest from which he has never returned.

The need to understand humans was coded into Tommy Hall’s DNA. He was born in Memphis, Tennessee, to a nurse named Margaret “Perky” Perkins and a doctor named Thomas James Hall. But music was also in his blood. He spent his formative years in jug-band country with an ear to the progressive jazz station and a record-collecting habit.

In 1961, Hall enrolled at the University of Texas at Austin, where he studied philosophy and psychology, fascinated with how the mind works. At night, he continued his musical education, hitting blues bars with songwriter — and future Elevators contributor — Powell St. John.

Austin introduced Hall to two future loves: an English major named Clementine Tausch and the drug lysergic acid diethylamide. For years they were a tightly knit trio, but it wasn’t love at first sight. Hall’s slicked-back hair and long beard were a turnoff for Tausch, added to what she calls terrific arrogance: “He was pretentious and always making pronunciamentos,” she says. A shave, a new suit, and Hall’s genuine affection helped change her mind; they married in 1964.

It’s impossible to pinpoint Hall’s first LSD trip; he estimated to Elevators biographer Paul Drummond that he’d dosed 317 times between 1966 and 1970. One of Hall’s initial experiences was profoundly negative. He was given the drug as part of a study at the UT lab, where he freaked out about all the scientists testing his paranoia levels. Hall realized then that chemicals have a valuable effect on the brain, but he was determined to explore LSD in more welcoming environments. This involved turning on the people closest to him, including his mother. (Perky was apparently ecstatic on acid, playing a Mozart record and repeating that she’d never realized the music had “all those things going on in it.”)

Hall was into deep thinkers, including G.I. Gurdjieff, whose philosophical writings had also influenced Bob Dylan. Gurdjieff believed there were four pathways to enlightenment, one of which was interpreted to be paved with drugs. Hall carried the 19th-century writer’s books everywhere, eager to spread Gurdjieff’s gospel. But by the mid-’60s, rock ‘n’ roll was doing the heavy proselytizing to the kids — Hall wanted this access to the masses.

Hall found the vessel for his lysergic prophecies when a friend invited him to a concert by the Spades, featuring 18-year-old frontman Roky Erickson. He heard the future in Erickson’s ravaged, bluesy screams — his singular voice is said to have influenced Texas pal Janis Joplin — and Erickson easily fell under Hall’s mentorship. Hall poached him from the Spades, matching him with a local group he liked called the Lingsmen.

Their first jam session took place in November 1965 at the Hall residence. Tommy doled out the LSD and grabbed a clay whiskey jug, eager to be part of the action. He ushered the instrument into the electric age, holding a mike in one hand and making noises into the jug’s interior, the echoes of his voice producing the Elevators’ ghostly je ne sais quoi. Hall’s primitive sound effects alternately came off like pigeons mating (“Earthquake”), emergency sirens (“Fire Engine”), and carnival rides (“Roller Coaster”).

“The first thing you notice, before anything really, is Tommy Hall’s electric jug sound,” notes Elevators fan Jim Reid of the Jesus and Mary Chain. “Never could quite work out how that sound was made.”

Second to Erickson’s soul-wrecked wail, that jug stamped the Elevators’ signature on the burgeoning psych scene of the mid-’60s. The group’s third charm was guitarist Stacy Sutherland, whose use of heavy reverb gave the group its acid-drenched garage-blues style.

Tausch claims she named the band, joining an “elevating” word with her lucky number 13. But the Elevators were nonetheless a remarkably unlucky act during their brief three-year run. Every time they’d catch a break (1967: lip-synching on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand!), something negative would counter the streak (Dick Clark steals their manager!)

Their biggest problems, however, came from their record label and the law. The Elevators signed to International Artists, a company many say kept the group in the poorhouse. Soon after the band formed, International Artists picked up its first single, “You’re Gonna Miss Me.” In 1966, the song had risen to #55 on the Billboard charts. That same year, the Elevators put their mark on a movement by titling their first official LP The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators. It became one of a string of records for which the band saw minuscule royalties.

Psychedelic Sounds’ artwork was unusual for the time, featuring swirls of color with a pyramid and an eye in the middle, a takeoff of the image on the back of the dollar bill. But most importantly for Hall, the record sleeve gave him space to deliver specific, if unsigned, messages about the philosophical quest for “pure sanity” that informed the album. Song titles came with his explanations, such as the revelation on “Reverberation” that you can reorganize your mind against self-doubt. “Tried to Hide” was a dismissal of superficial trippers. And “Splash 1” — a song written by Erickson and Tausch, who played den mother to the band — described the connection felt between two honest seekers.

In his lyrics, Hall penned elegant lines about trust: “Don’t fall down as you lift her/Don’t fall down/She believes in you,” and spiritual bonds: “She’s been always in your ear/Her voice sounds a tone within you/Listen to the words you hear.” There were also, of course, plenty of encouragements to take a magic blotter ride: “You finally find your helpless mind is trapped inside your skin/You want to leave, but you believe you won’t get back again.”

This new musical mysticism attracted a following in Texas. Elevators bassist Ronnie Leatherman remembers Hall hosting weeknight sessions in Houston where he’d play records and deliver his divine philosophies to gathered flocks.

As the band started touring Texas, though, young idealists weren’t the only ones listening. The Elevators lived in a conservative hotbed when, as drummer John Ike Walton tells it, rednecks were really red. The Elevators were seen as threatening to the very moral fabric of the state; their arrests were broadcast on television. Walton says the cops wanted to beat them up, cut off their hair, and throw them in jail. Band members spent time behind bars or were threatened with hard labor on the cotton farm for such minor violations as possession of a joint.

The Elevators decamped to the more supportive environs of San Francisco in 1966. With connections to Joplin and other Lone Star State buddies gone West, the group was quickly playing venues like the legendary Fillmore and the Avalon Ballroom, its audiences growing exponentially. The Elevators shared stages with the popular acts of the time: Big Brother and the Holding Company, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Moby Grape. They were embraced by the locals, despite having much shorter hair — a consequence of going through so many drug trials — and Hall occasionally getting smacked around for taking Richard Nixon’s side in political debates.

They were barely scraping by, though, getting paid $100 each for Avalon gigs, and by the beginning of 1967 they moved back to Texas. Deeper fractures also plagued the group. Hall’s insistence that the band “play the acid” every time they picked up an instrument was at odds with the members who didn’t enjoy the drug, and it was taking its toll on the ones who did.

The Elevators’ last hurrah came in the form of 1967’s Easter Everywhere. The landmark album was littered with allusions to Hall’s Eastern religious studies. The songs were ethereal love ballads lifted by exquisite harmonies (“She Lives (in a Time of Her Own)”); and parables with heavy visual imagery (“If your limbs begin dissolving/In the water that you tread/All surroundings are evolving/In the stream that clears your head”). The record’s lo-fi production value added to its eerie aesthetic, as did Hall’s photo on the back cover. He’s holding a finger to his lips in a warning to handle the mysteries of the universe cautiously.

From that minor peak the band fell mightily, starting in 1968. Erickson’s story became perhaps the most tragic. After becoming increasingly irrational on- and offstage, he cycled through mental institutions and in 1969 was locked up in Rusk State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Texas on drug charges, the final patch of dirt on the Elevators’ grave. Sutherland also entered dark times: He battled for years with hard drug addiction before being shot to death by his wife, Bunni, in 1978.

Hall’s path became more difficult to trace.

[….]

Read all of this article here / S F Weekly

Also see Austin Musician Benny Thurman Dead at 65 by Thorne Dreyer / The Rag Blog/ June 24, 2008

And Mesmo’s Reflections on the Sixties by Gerry Storm / The Rag Blog / June 21, 2008

Thanks to Bob Simmons / The Rag Blog

It doesn’t sound like psychodelic inspired insight led to health, wealth or peace of mind for any of those guys. Sad