The Huichol Deer Repopulation Project:

I learned that encroachment and poaching had decimated the deer population in Huichol land.

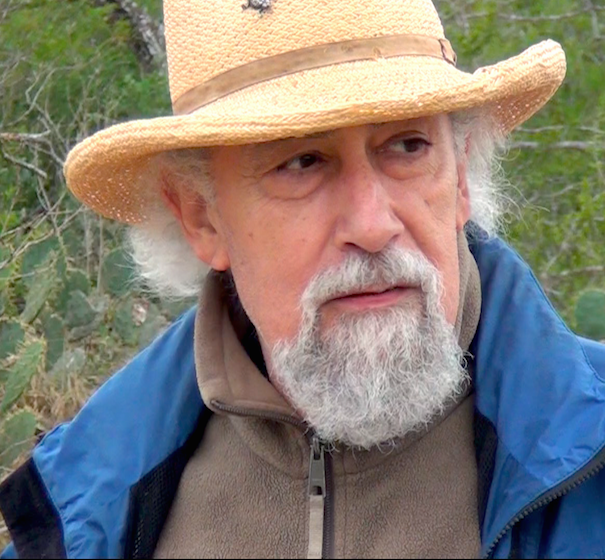

Artist and storyteller Luis Guerra was our guest on Rag Radio Friday, May 13, 2016. On the show, Luis talks about the amazing and ambitious adventure of securing and moving the Huichol deer that he discusses in this report. He also reminisces on his years with the

Artist and storyteller Luis Guerra was our guest on Rag Radio Friday, May 13, 2016. On the show, Luis talks about the amazing and ambitious adventure of securing and moving the Huichol deer that he discusses in this report. He also reminisces on his years with the  Huichol Indians, with emphasis on shared mystical experiences, and reads three stories about being in the mountains of Jalisco with the Huicholes.

Huichol Indians, with emphasis on shared mystical experiences, and reads three stories about being in the mountains of Jalisco with the Huicholes.

Listen to the podcast of our interview with Luis Guerra at the Internet Archive or on the player below:

In the last few months, the Huichol Deer Repopulation Project completed the relocation of 33 deer from northern Mexico to the Sierra Madre, in Jalisco. I am happy to offer the following report, which includes photographs of the capture, transport, and release phases, as well as of the people involved.

Background

The dream of repopulating the Sierra Madre of Jalisco with deer actually came to me about 28 years ago, when I attended the Huichol Festival of the Drum, the Corn, and the Squash. It was then that I learned that encroachment and poaching had decimated the deer population in Huichol land. Which was truly tragic, given that deer are sacred to the Huichol, an integral and major part of their cosmology.

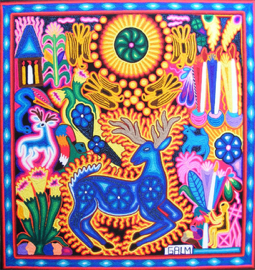

Venado Azul, Huichol yarn painting, by Marcos García López.

But it was three years ago, in 2013, at my 50th high-school (St. Joseph’s Academy, Laredo) reunion, that the idea became a plan. I struck up a conversation with one of my classmates, Abraham García, owner of a deer-hunting ranch, La Palma, near Nuevo Laredo. Abraham offered to help make the dream a reality by donating 30 doe and three bucks.

I then asked an old friend, Mateo Borghi, a respected healer and herbalist who has a home in those mountains, to coordinate the Jalisco side of this deer repopulation effort. Mateo immediately agreed, adding that his wife, Pati, who is Huichol, had recently had a vivid dream in which her childhood mountains were full of happy deer. I knew then that this project would be successful!

Phase 1: The corral, “friend-funding,” and a documentary

The corral

In 2014, I traveled with two of Abraham’s ranch-hands in a flatbed truck loaded with fencing materials provided by Abraham. We went from Rancho La Palma, in Tamaulipas, to Rancho El Laurel, in the Municipio (or “County”) of Villa Guerrero in Jalisco, situated between the Huichol and the Tepehuano lands. There we were met by a contingent organized by Mateo, and together we built a holding corral for the deer to be penned in while they acclimated to their new environment. The fence was eight feet high, and 100 meters square.

Friend-funding

In April of 2015, I started a “friend-funding” campaign to finance the capture and transport of the deer. La Peña, an Austin nonprofit organization, was kind enough to place the deer project under its umbrella. La Peña, founded by the sisters Lidia and Cynthia Pérez, has a long trajectory of supporting the arts in Central Texas and offering Latino cultural and educational programs and events for the community.

We were lucky to find many people eager to be a part of the project. Nevertheless, we failed to raise enough in time, so we missed the window for capturing and transporting the deer that year.

A documentary

As word spread about the project, many people suggested that it would make an ideal subject for a documentary. Sharon Greenhill, an Austin-based documentary producer, stepped up to the plate. Sharon has previously co-produced two documentaries dealing with Mexican culture: Agave Is Life and Chocolate: Pathway to the Gods. Sharon has formed Blue Deer Productions to be the framework for her documentary.

Phase 2: Capture and transport

The deer were captured by helicopter, January 20-21, 2016, at Rancho La Palma. (The helicopter was actually ready on the 19th, but it was too foggy that day.) A total of 21 deer were captured in those two days; 12 had already been captured, using tranquilizer darts.

This was the base of operations. On the hill in the back is the hunter’s lodge of Rancho La Palma. In the middle-ground is the helicopter that was used to capture the deer. In the foreground is the trailer that was used to transport 25 of the deer.

Cathy Reed and her husband, Kevin, of Dragonfly Aviation, a helicopter service based in Laredo, Texas, gave us a discount. Their crew of modern-day wranglers captured the deer professionally and efficiently.

Abraham donated all 33 deer. He also took care of the capture of nine doe and the three bucks. And of course, he got the permits necessary for transporting deer across state lines. He was hands-on throughout the entire operation. Not only did he pay for the veterinarian and have his ranch-hands assist Dragonfly and their crew, but he oversaw everything, from finding and scheduling the transport vehicles, to making sure we had the right feed for the deer. Rancho La Palma also provided accommodations for the Dragonfly crew and our documentary crew from Blue Deer Productions.

The helicopter delivers three doe to the trailer. Kevin Reed, the pilot, was as gentle as possible. Yet it seemed to me that these noble creatures felt, while not scared, a bit helpless. I asked them to forgive us for the indignity that we were causing them, and promised them that they would like their new home.

The ranch-hand Asiano (Chano) Mares (left) and the veterinarian Juan Pablo Orozco (right) are about to untangle two newly arrived doe. Chano was the indispensable deer whisperer. Juan Pablo examined every captured deer, then gave them an antibiotic shot and an analgesic.

The deer were placed in the trailer, and also packed into crates. As you can see, these are all young doe!

The bucks had their horns sawed off to protect them and their handlers during transport (they were also separated from each other, one in each crate). Their horns will of course grow back.

The capture was completed on the second day and we left immediately. It was two in the afternoon of Thursday, January 21. The truck with the crates is being followed by the truck with the trailer. The truck in the front is carrying three crates, holding a total of eight deer; the trailer is carrying 25 deer.

Once the animals are captured, there is no way to feed them or give them water until they reach their destination. I was eager to go. The 10-hour trip to Villa Guerrero (560 mi.) turned into a 17-hour trip, what with setbacks like a torn wire leading to the trailer’s taillight, hitting rush hour on the outskirts of Monterrey, and of course the many state, federal, and military inspection stops, where everyone wanted to see the deer, and of course check and double check our permits.

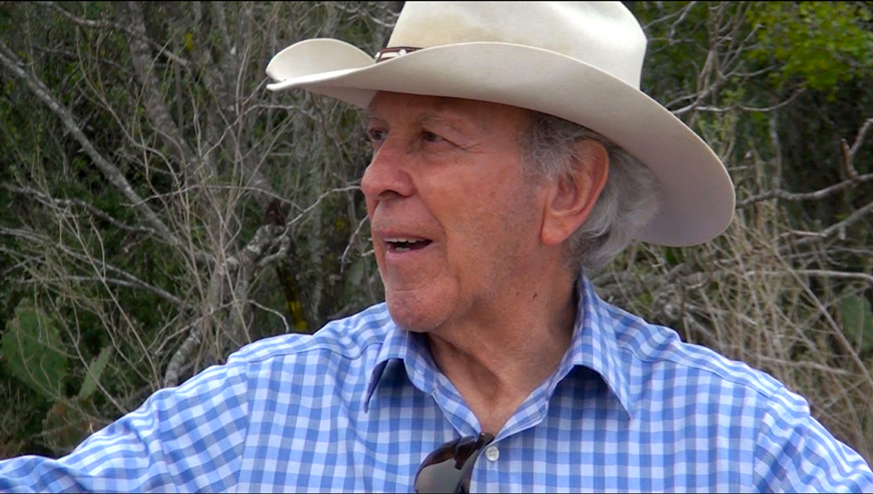

Mateo Borghi and his contingent were waiting for us at the outskirts of Villa Guerrero, Jalisco. They had been there since two in the morning, in freezing weather. We arrived at seven. We were greeted by Mateo, on the right, and Fabián Reyes, from the village of Atzqueltán, in the center. That’s me on the left, tired but happy to be there.

We have only two more hours to go to reach the holding corral, where Fabián will clear some tree stumps to allow the vehicles access to the gate.

On the way to Rancho el Laurel, we were met by a reception committee from the local communities. They were very excited to see the deer.

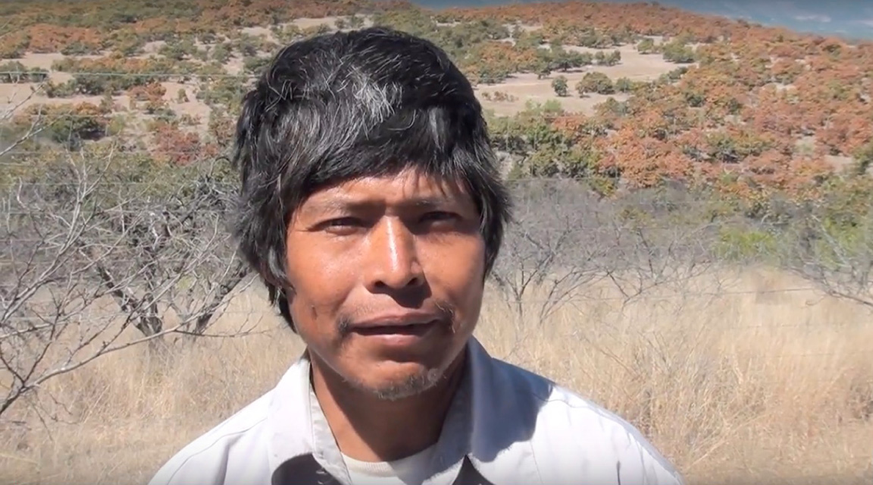

In the center is Tenón, Carrier of the Staff for the Huichol community of Rancho de Enmedio. On the right, Servando Ramírez, the ecologist for the Municipio of Villa Guerrero, explains the plan for game management. The plan is no hunting in the region for four years, and after that only the older deer.

Tenón was in full accord with the plan and promised that his community would respect it. He added that he would present the game-management plan to the gathering of leaders from all of the Huichol communities. Behind him is Guadalupe (Chito) Flores, the owner of Rancho El Laurel, who gave up some of his grazing land so that the deer could have a holding corral.

Mateo, on the left, will continue to work meeting with the community leaders in the Sierra to disseminate the game-management plan. Servando will be doing the same with the school teachers from the surrounding towns of Villa Guerrero and Bolaños. And Servando’s counterpart in adjacent Mezquitic, Selic Aguilar, will work with the teachers of his municipio.

We had our doubts, but the truck with the trailer and the truck with the crates both managed to make it over the roughest climb to the ranch with our valuable cargo unharmed.

On Friday, January 22, 2016, we delivered 30 doe and three bucks into the holding corral in the mountains of Jalisco. The deer were happy to jump out of the crates and the trailer. Now they could eat and drink, and move about!

This doe, newly arrived in the corral, looks back at us, bewildered. For all the trauma they endured, I never sensed that they were frightened, only puzzled.

Phase 3: Acclimation and release

The deer stayed in the 100-square-meter enclosure for a month. During that time, they were protected and provided with food and water by a Huichol family that camped next to the corral. The deer calmed down, grazed, became acquainted with their new environment, and mated. On Februarky 23, they were released.

One doe died soon after arriving in the corral. It was sad and disheartening, but I was told to expect a 10 percent loss, so I guess we did pretty good.

Ranch-hands and Huichol youths open the gate to the holding corral, preparing to release the deer, on February 23, 2016.

Presiliano Carrillo and his family had watched over the deer since their arrival. After being with the deer for a month, Presiliano said he felt they were his. He promised to look after them, that there may always be deer for their ceremonies.

Presiliano Carrillo’s mother, from Rancho de Enmedio, watched over the deer for a few days when Presiliano had to return to his ranch. She was also present during the release of the deer. She was happy to see deer in her mountains once again, adding that taking care of the doe made her feel they were her children.

Aldo Gamboa, Mayor of Villa Guerrero, was also in attendance. He was very appreciative of this gift and pledged the county administration’s full support for the game-management plan. He says their principal tasks are to raise awareness and enforce the regulations throughout the region.

Mateo Borghi has had the dream of repopulating the sierra with deer for decades. He is happy that his prayers have been answered, and that the community is becoming involved with the project. Yet he also knows that the years ahead are crucial to the success of the deer repopulation effort.

The deer — 29 doe and three bucks — left the corral together in a long, beautiful single file. They are now freely roaming the Huichol and Tepehuano mountains of Jalisco.

This is a panoramic view of the deer’s new home, the Sierra Madre of Jalisco and Nayarit.

Behind the camera is Ismael Trujillo, a dedicated videographer from San Luis Potosí. All these photographs are stills drawn from the raw footage taken by Ismael for the documentary being produced by Sharon Greenhill.

Gracias

Abraham’s donation of the deer was very generous. As were the hands-on contributions from people in Texas, Tamaulipas, Jalisco, San Luis Potosí, and the Distrito Federal. Not to mention the financial contributions from good folks from all over the United States and Mexico.

There are so many people committed to the success of this effort that my faith in humanity has been renewed. And my heart is filled with hope for our grandchildren’s great-great-grandchildren.

Thank you for taking the time to read this, and for being a part of this endeavor dedicated to our Mother, the Earth.

Going forward: What’s next?

The citizens of Villa Guerrero and the Huichol community have embraced the project and made it their own. And they would like to see the project continue. This is very encouraging. So encouraging, in fact, that Abraham is committed to donating another batch of deer for the coming year.

So it’s on! I am once again entrusted with the task of raising money. It will take $12,000 to pay for the capture and transport of the next batch of deer, and for holding, feeding, and protecting them during the acclimation period.

Project volunteers in Jalisco will salvage the holding corral and rebuild it in another area of the mountains. And already Mateo has initiated a fund-raising campaign in Mexico to help meet the $12,000 goal.

A request

I know times are hard, but even simply your blessings and well-wishes will help keep us going. Feel free to share this article with your friends.

But if you can, please send us your tax-deductible donation. Write a check to La Peña (indicating that it’s for the Deer Project) and mail it to: La Peña • 227 Congress Ave. • Austin, TX 78701.

Or contribute online by going to La Peña’s “Contact Us” page and clicking on “Donate.” Please indicate that it is for the Deer Project (in the “Add special instructions” box, in the “Review Donations” page).

And, by all means, please write me with your comments, suggestions, questions, or requests. You can reach me at GalleriaGuerra.com or through editor@theragblog.com.

[Luis Guerra is a painter, sculptor, writer, storyteller, and activist born in Piedras Negras, Coahuila, and raised in Laredo, Texas. Guerra’s art is in museums and collections in the U.S. and Mexico, and his stories are featured on National Public Radio’s Latino USA. Since 1985, he has divided his time between Austin, Texas, and Real de Catorce, a remote mountain village in the Mexican state of San Luis Potosí.]

This is an exciting and noble project. That entire region has very low numbers of deer. I wonder about the location, though. The article says the deer were relocated to “Huichol land,” but it seems Rancho de Enmedio is pretty far to the east of the official Wixárika (“Huichol”) territory. It’s even on the east side of the highway that includes the Crucero de Miguelón, often thought of as a highway that sort of divides the regions, though even on the west side of the highway there are Mestizo encroachments. To which Wixárika community does Rancho el Enmedio pertain?

Hawiekame, thank you for your interest and encouragement.

Forgive me for not responding sooner, but I wanted to first talk to Mateo Borghi. Since he is the coordinator of the Jalisco end of the project, I needed him to confirm my statements before I replied.

I was unable to reach him until just recently. He was in the Huichol Mountains, out of cell-phone reach. Mateo and the ecologist Servando Ramírez were visiting both Huichol and Mestizo communities, meeting with the elders and leaders, explaining that game management must be practiced to make sure that the deer thrive.

Rancho de Enmedio is indeed in the eastern area of the Sierra Huichol. It is between the three municipalities of Bolaños, Mezquitic, and Villa Guerrero. The Huichol communities of Rancho de Enmedio, San Antonio, Manillas, and El Tule all pertain to one of these municipalities.

The highway that I believe you speak of does not demarcate the eastern border of Huichol land, but rather divides the Sierra Huichol. It is the road that connects Bolaños to San Sebastián, Tuxpan, and Tenzompa, among others.

There has been at least one other effort, that I know of, that introduced deer to Huichol land, and I understand that it provided great hunting for a little while.

Mateo put a lot of thought into where the deer would be released. Rancho El Laurel, in the Municipio of Villa Guerrero, was strategically chosen. This part of the mountains is good habitat for deer, with plenty of vegetation and water. And it is not highly populated, allowing us the time to inform the inhabitants, both Huichol and Mestizo, of the importance of a game-management plan that will provide deer not for this season, but for future generations.

As the deer reach the more populated areas like Nueva Colonia, Las Latas, or La Barranca, for instance, the word will have reached the people, and hopefully everyone will be in sync with the game-management plan. Our prayer is that a tradition is established that will provide deer forever. A tradition that must belong to the Mestizo communities as much as it does to the Huichol.