Happy Easter,

But crucify him first

By Marc Estrin / The Rag Blog / April 3, 2010

This morning, the cheery NPR voice announced that today was Good Friday — but not for the Catholic Church, which was reeling from you know what. Good Friday — good.

I suppose it can be seen as good if you like nailing people onto crosses and the institutional power secreted from those wounds, but for most followers of Jesus Who Is Called The Christ, it’s a pretty sad end of the week.

Here in Happy-face Land, we love Easter, pink, white, and blooming. And now even Good Friday has been gobbled by Goodness. But George Fredrick Händel was not so easily scammed.

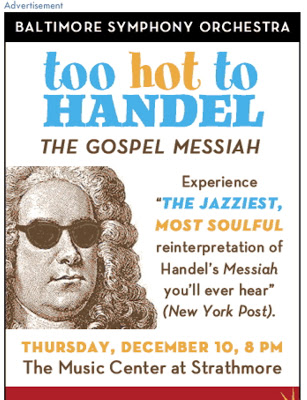

Most American performances of Messiah offer only the Christmas portion with tacked-on Hallelujah and Amen celebrating a babe not yet messiahed. But Messiah was written as an Easter piece, full of pain, suffering and transcendence. The familiar Christmas portion was a prologue only — to contrast with the anxious and metaphysical burden of the work. But Hallmark will have its way.

I am the president and only member of the National Bring Back Messiah As An Easter Piece Society. I have little influence on American cultural practice. But I do get to write novels with their interior rants.

Tweaking When the Gods Come Home to Roost for possible publication, I came across this short chapter I thought you of classical music persuasion might enjoy:

George’s Messiah

George loved Messiah. It was nothing a Jewish boy in Levittown had been expected to love, but it happened. Until he was fifteen, he had steered clear of this goyish mania. But one day, a lovely young girl with long, dark hair handed him a leaflet for an afternoon performance a busride away in Queens. Maybe she sang in the chorus. It must be all right for a Jew to go into a church, he thought, if it’s for a concert, and not to eat the body and blood. He wouldn’t tell his parents. They’d never know.

The young man was ravished by the experience. He used the word in every possible meaning: he was seized and violently done to; he was overcome by horror, joy and delight; he was pre-sexually bewitched, for the long-haired one was in fact singing soprano in the front row, and never had such an angelic voice issued from such sensuous purity. This concert was of the Easter portion of the work, and from “Behold the Lamb of God” to the last “Amen”; he was transfixed with wonder.

From the three bar mitzvahs he’d attended he knew Jews didn’t make this kind of sound. Synagogues were filled with the discordant rumble of davvenning, each worshipper finding his individual prayer voice and rhythm, chanting, whispering, singing, crying, repeating phrases over and over, lost in the brumming of the crowd. Sometimes a cantor sang. But this — this! It is music, music that hath ravished me! He got home at an unsuspicious five o’clock, and never mentioned his encounter.

He had tried to hear Messiah every year since then, but with all the changes that had occurred along the way, he had managed to bat only about .300. So what a boon — right here, in his own community, that he could conduct an annual Messiah! The sad part was that he could never share this joy with his family, old anti-clerical mom and pop ever more rigid in their disdain for religion. The idea of their very own son promoting Christ the Jew-killer might, he thought, send them each into heart failure. So this was his one activity he never called home about.

Choosing to do the Easter portion of Messiah for Christmas was George’s little revenge on America. Though written as an Easter piece, and traditionally performed in Europe during Easter time, in coming to America Messiah had shifted seasons, and along with them, content. Though the Puritans had banned the celebration of Christmas, post-Puritan America has embraced it with a vengeance, currently exhorting all to worship at the mall of one’s choice.

Perhaps in the land of the Easter Bunny and the lethal injection, crucifixion is seen as barbaric. Christmas, not Easter, is where most American celebration is concentrated, and with it, most concertizing. Messiah has become a Christmas piece, and most American performances restrict themselves to its first section concerning Advent and the birth of Christ. The meat of the oratorio is left out, and the introductory portion is capped with the Hallelujah chorus — a masterwork written to praise Christ’s ascent to his heavenly throne, unreported in these Hallmark card performances.

“A premature ejaculation at best,” George thought when feeling generous. But if Americans were determined to hear part of Messiah at Christmas, he was going to be damn sure it was the Easter portion that attacked them.

At 6:30 on the evening of the concert, Betty cell-phoned in to say that she had had a flat on I-680, that the AAA said they’d be there within fifteen minutes, and that being the case, she’d be at the church by ten after, and could they hold the performance? As if there were a choice.

So George came out at 7:05, and announced that the concert would begin at 7:20 because, as the contemporary world amply demonstrates, the Messiah always comes late. Then he did a remarkable thing, unexpected, certainly, because of his refusal of the first part of Messiah, but unexpected, ever, in any form, under the eye of God. He sat down at the Steinway, and played the slow opening of the opening “Symphony” of the work. Twenty-four stately, double-dotted measures marked grave — this the limit of his keyboard technique.

When the moment came for the Allegro moderato to begin, George stood up, walked to the curve of the piano as if for a vocal recital, placed his right hand on the rim of the case, and performed that three-part fugue all by himself. He whistled the soprano voice out of the right side of his mouth, the alto out of the left, and vocalized the bass part with accurate, wordless humming. You don’t believe this. It is true. Upwards of a hundred people heard it with their own ears. He must have been practicing this in the shower for the last twenty years in preparation for that night.

Now Messiah is one of the grandest works of western culture. It is simply not appropriate for a serious conductor to whistle the overture in public performance. But the effect, rather than being ridiculous, was to create a churchfull of gaping at the wonder that is man. No problem was too great for one who set his mind to it, no achievement too difficult. The room was riddled with people who had dedicated themselves to Bay Area excellence: none could gainsay George Helmstetter’s accomplishment.

Betty arrived, pumped and wired. The chorus filed on to the risers. In spite of George Bernard Shaw’s opinion alleging “the impossibility of obtaining justice for that work in a Christian country,” mid-Messiah instantly summoned the audience to pain and passion including even them, the guilt-free of the world. “Behold the Lamb of God,” the sacrifice upon whom all sins would be heaped and slaughtered into renewal, the Lamb whose blood would be smeared on door jambs to frighten Death away, the Lamb that would conquer the wolves, the conquering Lamb.

What about this Lamb? Handel took great pains to describe its scorn-filled whipping. “He gave his back to the smiters, and his cheeks to them that pluckèd off the hair.” Blood and hair clotting together on the prison floor. Here is perhaps the only major artwork which celebrates saliva as such: “He hid not his face from shame and spitting,” spit in the face, a cadence, ach-ptoo!

The listeners were assured, in no uncertain terms, that the Lamb was burdened with their very own doings: Surely he hath born our griefs, and carried our sorrows. The fierce F-minor cries, the painful, discordant suspensions: He was wounded for our transgressions; he was bruised for our iniquities, a catharsis of pity and terror.

Even the Jewish mothers of many in the audience would not have been able to evoke such a sense of guilt. The thoughtful were carried emotionally along, while at the same time wondering about the phenomenon of the Messiah. Is this suffering lamb the Saviour of the world? How odd.

The Messiah’s function is to be victorious. Christians thought of Christ. Jews thought through their own lens of the “true” reference, the continued oppression and persecution of Israel throughout the Christian and pre-Christian centuries — the Nazi destruction, the pogroms of the nineteenth century which had brought their parents to the New World, the persecutions of the eighteenth century, the seventeenth, and on back to the Exile, where the image of the Lamb converges with that of scattered Israel.

“And with His stripes we are healed.” What is that about? Why should one’s agony be inversely proportional to another’s? Conservation of Wound? Conservation of Tears? Conservation of Pain? Beckett has told us: “The tears of the world are a constant quantity. For each one who begins to weep somewhere else another stops. The same is true of the laugh.”

Handel lingers over the word “healed” as if to lay soothing balm upon Christ’s — and our — wounds. Yet even this very moment, was beyond a definitive scan. The perverse listener — and who is not perverse? — could easily hear the melismatic syllables of “healed” as “hee-hee-hee-hee-heeled,” in effect a subtle but demonic, underlying cackling, as if to say that no matter what the unction, the wound is too great to be cured — you’ll see. Hee-hee-hee. George was haunted by this dopplegängbanging effect, but was unable to phrase his way around it. The Lamb of God, and the sheep who have gone astray.

“All they that see him, laugh him to scorn. They shoot out their lips and shake their heads, saying”: Enter the scornful, the brutal choral metamorphosis from a confessing people of God to an unruly crowd in obscene play at a public execution. So does Jekyll turn unexpectedly to Hyde.

He trusted in God that He would deliver him: let Him deliver him, if he delight in him. Such assertive contemptuousness! The trivializing, de-legitimizing of God, putting his capitalized pronoun on a syncopated weak beat, now ironically, self-flatteringly strong. What pristine nastiness, abundantly clear. Thy rebuke hath broken His heart. He is full of heaviness. He lookèd for some to have pity on him. But there was no man, neither found he any, to comfort him.

Not only was this George’s favorite moment of Messiah, with the single most touching note in music slipping into place in the piano’s middle voice, a pensive entwinement of suffering and beauty. In the pause after pity on him, a luminous E rises half step to a questioning, consoling F, as if at least one human heart might go out to Jesus from the frigid emptiness answering his gaze.

But it was also the theological key to the work: Here was the heart of it. As every culture has known and proclaimed, something is wrong with the human race. Things are not as they should be. There have been many intellectual explanations — mythological, religious, philosophical. But here is the psalmist’s prophetic assessment: the primal fault is that we disdain God. We have turnèd everyone in his own way. The biblical word for this is “sin.”

Since by man came death… The listeners had to interpolate the moment of death. But George found this not egregious. The whole textual strategy of the Messiah is one of brilliant, evocative avoidance. Charles Jennens, an otherwise unremarkable British gentleman, had provided his friend George Fredrick with a libretto of theological genius, portraying every shade of devotion from piety, resignation and repentance to hope, faith and exultation.

And all this without resorting to narrative, as in the Passions of Bach: Christ did this, and then he did that, the misery composed directly into the music. The Messiah commands attention because of what it does not show, for the most part indicating, rather than depicting events. And therefore the death of Jesus, that epoch-making moment, really could exist as a lacuna between his unrewarded search for comfort and the triumphant Lift up your heads which followed. Praise be to Handel for demonstrating this.

Lift up your heads; The Lord gave the word; Their sound is gone out. And so, for the Jews, the Ark takes its place in the Temple, for the Christians, the Son takes his place in Heaven, and the preachers tell the world — but some do not hear. Why do the nations so furiously rage together? Tim Eckleburg stepped out to sing, less than accurately but with conviction, to sing of the kings of the earth, of the rulers that counsel together against the Lord.

Again, the demonic chorus: Let us break any bonds with the Anointed, and cast away their yokes from us. And what will happen? This time Willy Higinbotham, a “real” tenor from the Cal music department, stepped forward to describe the smashing and breaking that will ensue, an image which always reminded George of the piled up debris confronting Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History.

And then, the great moment, the moment incoherently misplaced in American versions, the phenomenal Hallelujah Chorus. The piling up of debris? Hallelujah! For the Lord God Omnipotent reigneth — which at first blush is not a very encouraging vision of the future. But what if it were to become the case — that the kingdom of this world is become the kingdom of our Lord, and that over such a peaceable kingdom He shall reign forever and ever ? It did give one pause, in the midst of the war on drugs and the war on terror.

Almost three hundred years earlier, King George had stood in his excitement, dragging the court to its surprised feet around him, and now the audience at the Mt. Diablo Unitarian-Universalist Church took this traditional ninth inning stretch incapable, however, of diverting the impregnable momentum of the music.

For all the radiance of the performance, there was one moment that stood out above all others. Dr. T.J. Eckleburg, with his strong baritone, came in too soon after George’s breathtaking pause before the final cadence, shattering the loudest silence in creation. After the concert, BB commented to another alto: “I’ve sung Messiah many times in my life,” she said, “and I’ve always waited for someone to come in too soon. It was very satisfying to me.”

[Marc Estrin is a writer and activist, living in Burlington, Vermont. His novels, Insect Dreams, The Half Life of Gregor Samsa, The Education of Arnold Hitler, Golem Song, and The Lamentations of Julius Marantz have won critical acclaim. His memoir, Rehearsing With Gods: Photographs and Essays on the Bread & Puppet Theater (with Ron Simon, photographer) won a 2004 theater book of the year award. He is currently working on a novel about the dead Tchaikovsky.]