Music hath charms to

soothe the stinking breath

By Marc Estrin / The Rag Blog / December 13, 2010

A recent revelation: rehearsing the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto, I was in the cello section mentally drooling over the carpet of harmonies we were laying down under the solo violin during the gorgeous slow movement. Not much to concentrate on other then how very beautiful this moment was.

As I breathed in the slow movement of the Mendelssohn, I realized that this music, this moment, and others like it, were SPECIFIC antidotes to the poison spewing from the mouths of politicians. I realized too, that without my frequent hits from the music inhaler I would probably be dead, or at least reduced to zombiedom. My life’s balance was suspended between the poison of politics and the healing of music, which interaction created a space for my writing.

I had long been aware of “the healing power of music” inasmuch as it was the arena of “music therapy” and the tool of music therapists. But I had never been so acutely aware of its specific purgative and remedial effect.

Coming up soon are Beethoven’s two birthdays, December 16 and December 17. As one of the characters in my novel, Insect Dreams, says: “Extraordinary people do extraordinary things.” (Not to be coy, there are two different documents with two different birth dates. I celebrate both.) And this week, too, Donna and I begin rehearsals for a New Year’s Day performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, which will hopefully become a tradition here in Burlington, Vermont. In any case, Beethoven is often on my mind.

It’s somewhat predictable, then, that the combination of Beethoven, music, and healing would find its way into my writing. I want to share with you this week a particularly ridiculous scene based on a particularly amazing piece of music — a movement of the A minor String Quartet which Aldous Huxley called “proof of the existence of God.” The movement was labeled by Beethoven “Heiliger Dankgesang eines Gesenenen an die Gottheit, in der lydischen Tonart”–a “Holy Song of Thanks from a Convalescent to the Godhead, in the Lydian Mode.”

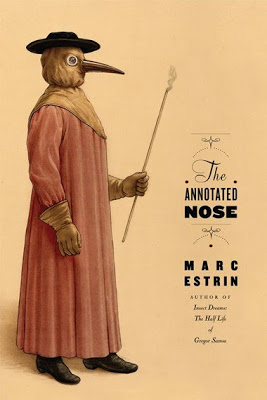

Beethoven was known to have serious stomach problems which bothered him increasingly as he aged. I put this all together and came up with the following note in my recent novel, The Annotated Nose.

The hero, Alexei Pigov, has become the Glenn Gould of the accordion. He is befriended by a fellow lab tech, William Hundwasser, who exploits and markets his strangeness, creating from him the public figure of a medieval plague doctor come to heal The Contemporary Plague. Here he is in Hundwasser’s lab, experimenting with Beethoven on Hundwasser, and Herman, the tarantula:

44. Studying tarantellas and subtly applying them was my first experience of being a healer. Hundwasser kept several in a terrarium in his lab as a conversation starter for the “pretty young things in their white lab coats” he enjoyed cultivating. I began with one named Herman.

Herman was a dancin’ fool. He (?) would jump out of hiding — or hibernating, or estivating, or whatever tarantulas do for sleep — at the first peep of the accordion, and would then stand thoughtfully, taking the music into his ganglia. Then he would begin to sway, and after a minute to dance, and to dance appropriately to whatever I was playing, almost in rhythm, but definitely fast for allegros and slowly for adagios. When I stopped, he stopped — and waited. He could outwait me. When I left, I would just leave him there, waiting.

I figured if an insect person could react this way, with so few nerve cells, human persons must be able to process such signals with far more complex consequences than simply dancing.

As you probably know, Beethoven suffered from chronic abdominal problems and severe intestinal inflammation. Fortunately Hundwasser suffered similar symptoms. An experiment was staring me right in the face. The famous Heilige Dankgesang in the A minor quartet, the “Holy Song Of Thanks From A Convalescent To The Godhead,” was written after recovering from a serious bout with abdominal pain. Surely the tones, the great ideas of that movement, beyond being “proof of the existence of God” (Huxley), the successive integrations of disparate elements, must have something to do with disease, and with (Beethoven’s) stomach disease in particular. It was worth a try.

I made an accordion arrangement of the three adagio sections, and played them daily to Hundwasser during lunch break. We used the animal room for privacy. He just sat and listened. I suppose the rats listened too, but I had no parameters to measure the effects on them.

Hundwasser, however, had lots of parameters. Or, like the hedgehog, one big parameter: the number of Rolaids he popped each day. It took a week or so before R began to drop. From an average of 20 to an average of 12. On weekends, no music, R rose again. Come weekdays, it began to fall by Tuesday. In a sustained three week experiment, no days off, R fell to 3, then climbed to 12 again with a week off. We were on to something.

Neither of us had the time for a full and lasting cure, but after we stopped the experiment, he bought a record of the Budapest playing it, and has used that routinely to calm his symptoms. Saves him money on Rolaids, and he can listen while washing the dishes during the rare moments that he washes the dishes.

Flush with success, I looked more closely into the tarantella situation, the Antidotum Tarantulae. I would need to study the phenomenon first hand.

But there aren’t a lot of tarantula bites in Manhattan. There aren’t many tarantas [women bitten by tarantulas] to whom I could offer treatment — especially if it were just an experiment by a newbie. What to do?

Herman to the rescue! I could get him to bite me, and then, in the heroic tradition of the great doctors and medical researchers, I could try to cure myself. I admit such research is small potatoes compared to the guy who shoved a catheter into an arm vein and guided it up into his heart, or the guys from Walter Reed’s team who invited malaria mosquitoes to bite them, so they could test drugs, or even the guy who gave himself ulcers so he could prove it was bacteria that caused them. Small potatoes unless I died. But I know that though tarantula bites were toxic, they were not often fatal.

And of course, we have to remember Dr. Curt Conners, aka, the Lizard in Spiderman Comics, who lost his arm in a war, and experimented with reptilian DNA to try and grow it back, a great example of be careful what you wish for: the therapy caused him to mutate into a creature half-human and half-reptile. He became a villain, too, and even uglier than I am. I wondered if I might turn into a tarantula person — from the saliva — but it wasn’t very likely.

I knew this self-experimentation would be looked down upon at the Berg Institute for Experimental Physiology, Surgery and Pathology, even though experimental physiology, surgery and pathology was exactly what I was doing. So it was 1 A.M. when I let myself into Hundwasser’s lab, took Honey [his accordion] out of her case, and aroused Herman with the traditional slow, lamenting introduction to Borodin’s Polovetsian Dance #2, “The Wild Dance of the Men.”

Out he came on cue, staring at me through the Adagio, and when the fast part started, gave a shiver, and went into nothing short of a frenzy, leaping high off the terrarium floor, doing 90º, 180º, 270º, and 360º spins in the air, landing on his feet, rolling over on his back, and dragging himself miraculously by hyper–extended forelegs reaching up, over and behind his head, engaging the sand. It was so amazing, I almost forgot what I had come for. He must have been a Polovetsian spider, or at least have Polovetsian blood, perhaps from the Russian steppes.

When the both of us stopped to get our breaths, I thrust my left arm into the terrarium, and, though normally a pacifist, he leaped at it, and sunk his fangs in midway between wrist and elbow. Good Herman! I had to pull him off. Within a minute and a half, I was, as they say, possessed by the spider.

Though being somewhat atypical myself, I was that night afflicted with all the typical tarantula bite symptoms: feelings of prostration, anguish, psychomotor agitation, clouding of my sensory apparatus, difficulty standing, stomach cramps, nausea, paresthesia, muscular pains, extraordinary itching, and best and worst of all, vastly heightened sexual desire. I took a cab home; the cabbie thought I was way-drunk.

Lying in my bed, I felt wounded and weary, and aware of the deep tediousness of all things. Still, after a short sleep, I was able to drag Honey out of her case, and begin a medley of tarantellas I had learned.

Somewhere toward the end of the 1490s, the great Neopolitan scholar Alessandro d’Alessandro described the treatment of stricken tarantas by the local folk musicians: “they play different dances according to the nature of the poison, in such a way that with the victims entranced by the harmony and fascinated by what they hear, the poison either dissolves inside the body and dissipates, or else is slowly eliminated through the veins.” And with (wouldn’t you know it?) one of the Neopolitan tarantellas, I could feel just that effect, a veritable exorcism, a return to life, possibly to love. By the next day I was weak, but feeling basically normal via my iatromusical practice.

Plague doctoring is not so much different, though I suffer less, and my patients suffer more.

[Marc Estrin is a writer, activist, and cellist, living in Burlington, Vermont. His novels, Insect Dreams, The Half Life of Gregor Samsa, The Education of Arnold Hitler, Golem Song, and The Lamentations of Julius Marantz have won critical acclaim. His memoir, Rehearsing With Gods: Photographs and Essays on the Bread & Puppet Theater (with Ron Simon, photographer) won a 2004 theater book of the year award. He is currently working on a novel about the dead Tchaikovsky.]