Radical art is an act of uncompromising passionate resistance.

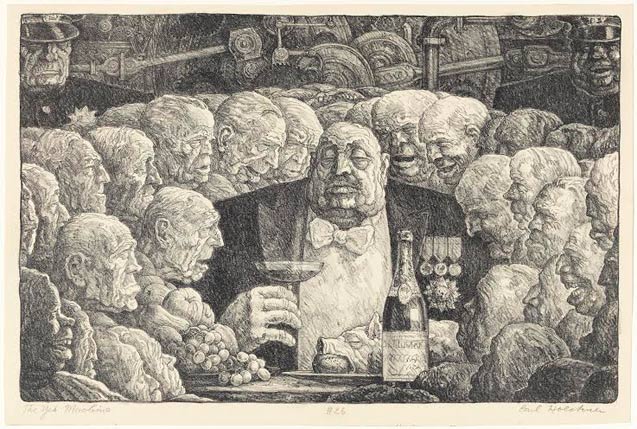

Carl Hoeckner, “The Yes Machine,” c. 1935 (Lithograph: Courtesy of Mary and Leigh Block Museum, Northwestern University). Image from Truthout.

Marxian playwright Bertolt Brecht declared of revolutionary art: “Art is not a mirror held up to reality, but a hammer with which to shape it.” Brecht’s artistic career in Germany (except for his exile during the Nazi era, after which he returned to found the Berliner Ensemble Theater company in East Berlin) spanned from the Russian Revolution to his death in 1956 — and his work illustrated that revolutionary art must avoid the pitfalls of becoming co-opted by propaganda or commercialization.

Brecht believed that to be a radical and revolutionary artist is to be defiant of any imposition of form or content by any economic system, artistic academy, or political status quo.

Mother Courage and Her Children, considered by some as the theatrical masterpiece of the 20th Century, combines a radical aesthetic with an anti-fascist theme: The masses suffer from wars fought to enrich profiteers. But Brecht also kept his distance from the Soviet-mandated art that glorified Stalin and communism.

Can art in a museum exhibition be radical?

Brecht’s concept of radical art as a social weapon is not limited to theater. An exhibition, The Left Front: Radical Art in the “Red Decade,” 1929-1940, currently running at the Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, offers a visual history of radical pictorial art during the Depression era.

It might appear ironic that radical art would be exhibited within a museum since museums were normally considered by revolutionaries to be the cemeteries of bourgeois creativity.

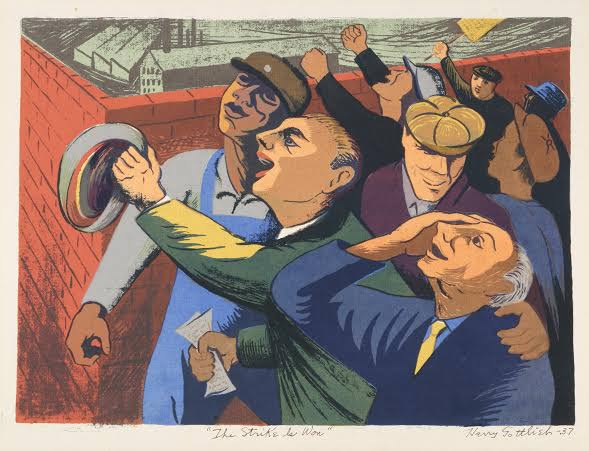

Harry Gottlieb, “The Strike Is Won,” 1937 (Screenprint: Courtesy of Mary and Leigh Block Museum, Northwestern University). Image from Truthout.

However, the Block Museum created the exhibition with the goal of avoiding this death knell by focusing on art that “engages in the struggle for power.”

The Left Front is meant to initiate a dialogue about the nature of radical art through the exploration of a crucial historical period in the United States when capitalism was potentially on the ropes. The museum has been offering a series of events to further the dialogue on radical art in the form of films, poetry readings, spontaneous performances in the exhibit area and even an open forum — “An Artists’ Congress: What is Revolutionary Art Today?” — on May 17.

A newspaper blog filled with diverse viewpoints on radical art and detailed historical information (reminiscent of a political leaflet) is available at the exhibit — and also can be read, in part, online.

The range of viewpoints expressed in material and presentations associated with the exhibit are reminders that defining radical art ipso facto invites debate.

Radical art in the ‘Red Decade’

The Left Front: Radical Art in the “Red Decade” (running through June 22) is a point of departure for this conversation. For instance, can visual paintings or drawings that depict an oppressive plutocracy — and portray the dreary life of workers in the ’30s — cause enough indignation to incite transformative change, then or now? Does art need to be public and visible to masses of people to have an impact? What is proletarian art? Should there be a division between Artists with a big “A” and art of the masses. Who is the arbiter of radical art? Does such art need to fully achieve revolutionary change to be considered successful?

The exhibit — and events associated with it — evoke a plethora of questions about what constitutes an art that is elusive by the very nature of its creative challenge, particularly as external circumstances change over time.

Radical Art in the “Red Decade” exhibits paintings, woodcuts, sketches, and other visual art, primarily produced by artists who were in John Reed Clubs (JRC) — named after the U.S. journalist who covered the Russian Revolution and is the only U.S. citizen buried within the Kremlin grounds. Artists in the John Reed Clubs generally supported the Soviet Revolution and developed a manifesto in 1932 in New York that included the following goals:

- Fight against imperialist war, defend the Soviet Union against capitalist aggression

- Fight against fascism, whether open or concealed, like social-fascists

- Fight for the development and strengthening of the revolutionary labor movement

The manifesto concluded with a rousing appeal to U.S. artists:

We call upon all honest intellectuals, all honest writers and artists, to abandon decisively the treacherous illusions that art can exist for art’s sake, or that the artist can remain remote from the historic conflicts in which all men must take sides. We call upon them to break with bourgeois ideas which seek to conceal the violence and fraud, the corruption and decay of capitalist society.

ArtDaily.org writes of the exhibit at the Block Museum:

The Left Front is divided into two chronologically driven themes: the Revolutionary Front 1929-1935 and the Popular Front 1935-1940. Artworks featured in the “Revolutionary Front” correspond to the aims and ambitions of the JRC, with its emphasis on the artist’s role in elevating the working class and the use of art as a “weapon” to combat social ills. The “Popular Front” considers the transition in the mid-1930s from the militant tone of the JRC towards the broad-minded approach of the [American Artists’ Congress] AAC, which sought to unite radical leftists and centrist liberals in a shared battle against fascism.

Within these chronological guideposts, the exhibition explores six key themes of activism and collectivity. The first subsections “Class Struggle” and “Workers of the World Unite!” explore JRC artists at their most uncompromising. These sections interpret the iconography of works such as Harry Sternberg’s haunting “Steel Town” lithographs by returning to the writings of economic theorist Karl Marx, whose essays provided artists on the left with a vocabulary to describe the destructive qualities of capitalism. In these works, the industrial production takes on a brooding, almost sublime quality of desolation. Alexander Stavenitz’s intaglio print, Subway No. 2, shows the alienation and loneliness of a homeless subway rider. Stavenitz’s image contrasts dramatically with Carl Hoeckner’s The Yes Machine, an indictment of a wealthy but withered capitalist surrounded by ugly and obsequious “yes men….”

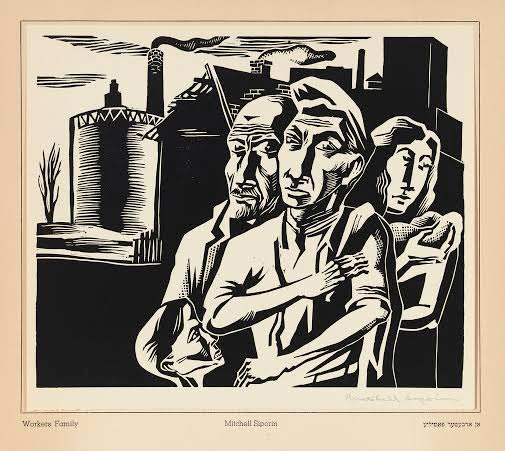

Mitchell Siporin, “Workers Family,” 1937 (Woodcut: Courtesy of Mary and Leigh Block Museum, Northwestern University). Image from Truthout.

However, by the end of the ’30s Stalin had signed a non-aggression pact with Hitler, and the independent proletarian movement of art in the Soviet Union had been entirely absorbed into a propaganda strategy to bolster authoritarian communist rule. World War II was also looming as the threat of Hitler and grave tensions with Japan intensified. These and other factors contributed to the demise of the John Reed Clubs.

Revolutionary artis anti-hierarchical

Indeed, in the ’30s a split had opened within the U.S. Marxist artists between artistic subservience to the creation of a dictatorship of the proletariat (as mandated by the Politburo in the Soviet Union) and proponents of art as an individual and communal weapon against all tyrannical hierarchies.

This, in many ways was symbolized by the split between Stalin and Trotsky, which, in one example, manifested itself in different perspectives on art — an offshoot of their disagreement about the overall direction of communism between centralized brutal control (Stalin) and an ongoing populist proletarian revolution (Trotsky). The feud over international communist leadership ended when Stalin had Trotsky assassinated in Mexico City in 1940.

Trotsky had sought refuge in Mexico, and it is informative to understand the political and artistic theories that he shared with famed Mexican muralist Diego Rivera — who sponsored his entry into that country — in order to better understand the heated arguments over radical art during the tumultuous Depression and post-Russian revolutionary period.

In the mid-30’s, Diego Rivera, André Breton, and Trotsky (as the assumed editor) issued a manifesto: “Towards a Free Revolutionary Art.” Rivera, Breton, and Trotsky asserted,

We recognize that only the social revolution can sweep clean the path for a new culture. If, however, we reject all solidarity with the bureaucracy now in control of the Soviet Union, it is precisely because, in our eyes, it represents, not communism, but its most treacherous and dangerous enemy.

They believed that art should belong to the working people, that it should be public, and that it should be anti-bourgeois. The artist (or art collective), they said, should not be constrained by a straitjacketed ideology of the state (even if it is purportedly proletariat). Art represented liberation of the creative spirit that would facilitate a path toward the elimination of economic oppression and social injustice (including war, torture, and mass murder).

An analysis of the “Free Revolutionary Art” declaration in a 2008 article in Socialism Today describes the significance of their collective manifesto, which had been originally published in The Partisan Review:

The manifesto explained the role artists could play in exposing the real nature of these systems. It rejected controls on artistic expression: “In the realm of artistic creation, the imagination must escape from all constraint and must under no pretext allow itself to be placed under bonds… and we repeat our deliberate intentions of standing by the formula, complete freedom for art.”

Many potential traps await the radical artist

Many traps, nonetheless, await the artist who dares to not conform. Socialism Today pointed out that individual artists and movements can be radical, but perennially run the risk of being co-opted by wealthy collectors who patronize art galleries and build private collections, and by museums who decide what art falls into an acceptable category that will not roil the status quo. Socialism Today uses the surrealist movement as an example:

Surrealism’s roots were in the nihilistic western Dada art movement of the beginning of the 20th century. The international mass radicalization accompanying the latter years of the first world war — illustrated most spectacularly by the Russian revolution of 1917 when working-class people, guided by a mass Marxist party, actually took power — had its impact on artists as it had on all sections of society.

The surrealists came out of that maelstrom. Made up of many different individuals and trends, incorporating many different ideas, using a variety of media, surrealism was an overwhelmingly radical, left-wing movement.

In the end, however, the mainstream surrealists became artistically embraced by the commercial and cultural salon of Western art: galleries, museums, and art “experts.” Some of the surrealists became fashionable among the wealthy — and began to paint for the value of their work in the marketplace.

Such are the risks that radical art can become an acquisition of the ruling elite, thus defanging its power.

Radical art is accessible to the public

Diego Rivera believed that his radical art celebrating — among other subjects in his Mexican work — labor, indigenous people, the 1910 Mexican Revolution, and Marxism, was best conveyed through public murals, accessible to all. Rivera recognized that a key characteristic of art that made it into the cultural canon was its limited visibility to the masses — as well as its general failure to challenge the existing oligarchical order (although exceptions exist in works such as Picasso’s “Guernica”).

Influenced by Rivera, the New Deal Works Progress Administration (WPA) hired U.S. artists to create murals in public spaces, some of which — many glorifying the work of the laborer — are still visible in older government buildings. However, an ardently Soviet-aligned faction of depression era artists objected that although the WPA murals restored dignity to workers, they failed to sufficiently depict ownership exploitation. In short, were many of the WPA art projects not radical enough? The fierce arguments on radical art raged on.

Rivera as an example of the threat of co-option of radical art

Rivera himself illustrated that radical artists often found it challenging to fully maintain their principles in the face of the practical realities of survival and funding for their efforts. Indeed, Rivera accepted a commission in 1932 from Edsel Ford to paint the Detroit Industry Murals in a courtyard at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Sanctioned by Ford’s approval, the key panels (among 27) depict productive workers on the Ford assembly line at its then River Rouge Plant. There is no emphasis on worker exploitation or grievances, although other sections of the work caused controversy for alleged irreverence.

In an iconic pairing of a Marxist and member of a premier U.S. capitalist family, Nelson Rockefeller chose Rivera to create a mural — “Man at the Crossroads Looking With Hope and High Vision to the Choosing of a New and Better Future” — for the lobby of Rockefeller Center in 1933. This philanthropist-artist collaboration had a different outcome than in Detroit.

Rivera was paid for his work, which showed the indolence and squandering of the rich in contrast to the new social order offered by Lenin. Rockefeller ordered a rendition of Lenin surrounded by appreciative workers removed from the mural, but Rivera refused. Within a few months the mural disappeared and Rivera re-created it at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico. Rivera’s revenge was adding Marx and Engels to the new version of the mural with a drunken John D. Rockefeller carousing with a woman at a nightclub, a dish of syphilis bacteria placed above their heads.

Diego Rivera panel for Rockefeller Center that was destroyed by Nelson Rockefeller, “Man at the Crossroads,” 1933. Image from Wikimedia Commons / Truthout.

Image of Lenin that Nelson Rockefeller objected to in Diego Rivera Rockefeller Center mural, 1933. (Image from Wikimedia Commons / Truthout.

Rivera’s dilemma illustrates the moral conflicts that develop when financial patronage collides with a radical artistic and a political vision. Indeed, the Detroit and Rockefeller Center commissions were cultural confrontations about radical art being played out during the early years of the Depression, as seen in the “Left Front” exhibition.

Nevertheless, Rivera used money from his U.S. commissions to create fully public and radical art in Mexico. Was his dalliance with U.S. financial barons worth the price? The answer to that question summons differing viewpoints and represents a continuing dilemma for radical artists.

Indeed, let’s fast forward to the post-millennial time period. Radical multi-format artist Anne Elizabeth Moore wrote a trenchant and revealing book in 2007, Unmarketable: Brandalism, Copyfighting, Mocketing, and the Erosion of Integrity, about how the marketing professions and corporations — which are even more advanced now in their capabilities due to the Internet — are co-opting underground culture and anti-hierarchical and irreverent art such as graffiti and street and building murals. Even some of the works of subversive street artists (such as Banksy) are now being sold for large sums in galleries. However, the style is primarily what is heisted and rebranded as hip and fashionable.

Radical art transforms inner selves and relationships

Radical art is not limited, as was noted earlier, to one particular medium.

Mark Nowak is a poet who writes about members of the working class. As a speaker at a “Left Front” program, he illustrated that radical artwork, in this case his poetry, should ideally move from the “I” to the “we.” Nowak — an associate professor at Manhattanville College — for instance, wrote a book of poems, Coal Mountain Elementary, about the travails and dangers of being a coal miner and then created an auxiliary website.

On the Internet, Nowak updates news on coal mining exploitation, collapses, blasts, and deaths around the world. His poetry extends beyond the written page by maintaining a record of the industry’s toll — an ongoing “job for living people working in hell” (as a person says in his book) — that is internationally accessible.

As another means of transforming community through art, Nowak conducts poetry sessions with laborers, including domestic and automobile assembly workers. Nowak told Truthout that he views these sessions as empowering, providing dignity to those for whom he serves as a facilitator: “They generally have no one outside their families who will listen to their stories and concerns.”

By focusing on their lives and jobs, Nowak gives them a voice that they did not know they had. “Poetry has changed them,” Nowak says. He believes that their new sense of empowerment and self-value, acquired through the poetry workshops, may move them toward a more assertive stance on behalf of their social and economic condition.

Moore (who writes and leads the “Ladydrawers” series on Truthout and is on the faculty of the Art Institute of Chicago), asserts that radical art “always fundamentally reforms human relationships. Also, the primary emotional experience of revolutionary art today is one of pain and discomfort, although a deep joy is available in its making and following its discovery is the reason it thrives at all.”

Radical art then, from such a perspective, must transform the viewer (or reader). In the “Left Front” exhibit, much of the artwork was aimed at creating public indignation through focusing on the squalid conditions and desperate images of exploited laborers and the unemployed — and by creating gluttonous portrayals of industrial profiteers.

Community involvement in radical art

Radical Art in the ‘Red Decade” also recounts how the John Reed Clubs tried to reach out to working-class communities through organizations such as Chicago’s Jane Addams Hull-House Settlement.

The use of community members as interactive participants in creating radical art is a vital part of many contemporary acts of resistance. Activist art can turn a protest into a spectacle, from an event ignored to one that impacts both the collective creators of the art and those who view it. This is also readily apparent in murals that inform and galvanize public audiences.

As Tatiana Makovkin, an organizer with Creative Resistance (a project of Popular Resistance), wrote recently: “Art is good for our communities, and artistic collaboration is a bonding experience. We make art together, not just because of the changes it can bring to the world around us, but because of the way it changes us internally.”

In one of her recent art performances, Anne Elizabeth Moore challenged the audience to participate in her artistic process by cutting up a pair of blue jeans that were produced by low-cost, near-slave labor overseas. With such an action, radical art becomes shared and the division between artist and audience blurred.

Indeed, radical art ideally moves from the creator to the community, creating ripples of impact and change.

The intersection of individual creativity and political context

Carolyn Forché, an acclaimed poet known for her advocacy of bearing witness to human rights injustices, writes of poetry of resistance:

We are accustomed to rather easy categories: we distinguish between “personal” and “political” poems… The distinction…gives the political realm too much and too little scope; at the same time, it renders the personal too important and not important enough. If we give up the dimension of the personal, we risk relinquishing one of the most powerful sites of resistance. The celebration of the personal, however, can indicate a myopia, an inability to see how larger structures of the economy and the state circumscribe, if not determine, the fragile realm of the individual.

Forché doesn’t consider herself to be a radical artist with a political agenda; however, she asserts that bearing witness to injustice through poetry is a radicalizing act. The distinction represents one of those nuances of radical art itself, in that it may encompass those in the arts who document societal oppression and the violation of human rights but who don’t see themselves as expressing an overtly political agenda.

Poets such as Forché (many of these poets are found in her two large anthologies: Against Forgetting: Twentieth Century Poetry of Witness and Poetry of Witness: The Tradition in English, 1500 – 2001) create, she writes, in a “sphere in which claims against the political order are made in the name of justice.”

The radical artist (visual, cinematic or written) recognizes that the political and personal are as entangled as roots of two large oaks growing side by side. Personal creativity is interwoven with a passionate insight into social and political context regardless of the artistic medium.

The Left Front: Radical Art in the “Red Decade” exhibition is a reminder that radical art is always evolving. As a rebellious deviation from proscribed artistic convention, it can never become ossified.

It must be robustly resilient in responding to the political and systemic reality of the moment — and defiantly and creatively uncompromising in order to engage, transform, and radicalize communities and society at large.

Note: Many of the artists and ideas referenced in this analysis are not in the “Left Front” exhibit (which focuses on radical U.S. art of the ’30s). They, however, illustrate the ongoing conversation about the role and substance of radical art in an evolving society.

This article is copyright Truthout where it first appeared. It may not be reprinted without permission.

[Mark Karlin is the editor of BuzzFlash at Truthout. He served as editor and publisher of BuzzFlash for 10 years before joining Truthout in 2010. BuzzFlash has won four Project Censored Awards. Karlin writes a commentary five days a week for BuzzFlash, as well as articles for Truthout. He also interviews authors and filmmakers whose works are featured in Truthout‘s Progressive Picks of the Week.]

I don’t see that’s there’s any distinction between art for art’s sake and art for the peoples’ sake. By definition art is for everyone.