The Wall Street occupations and the

making of a global counterculture

The emergence of a global youth counterculture should be seen as a powerful complement to a global movement for freedom, democracy, and economic justice.

By Mark Naison / The Rag Blog / October 5, 2011

NEW YORK — On Monday, October 3, I spent about an hour in Liberty Plaza, sitting, walking around, and talking to people before the event I had come for — a “Grade-In” organized by teacher activists — finally began, and was stunned by how different the occupation was from any demonstration I had attended recently.

First of all, in contrast to the last two protests I had participated in — a Wisconsin Solidarity rally at City Hall, and the Save Our Schools March on Washington — I saw few people my own age and no one I recognized at — least until the “Grade-In” started

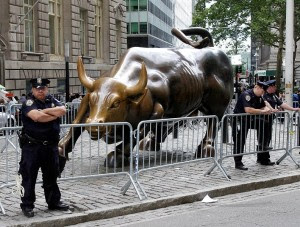

When I arrived, at 11 a.m., most of the people in Liberty Plaza were the ones who had slept there overnight, and the vast majority were in their 20’s and 30’s — a half to a third my age. They were drumming, sweeping the sidewalk, talking to curious visitors — who were still few in number — eating or chilling with one another, and their relaxed demeanor blew me away given the tumultuous events of the day before when more than 700 protesters had been arrested by the NYPD after marching onto the Brooklyn Bridge.

They were also, to my surprise, thoroughly international. Many of the people I met at the information desk, or who spontaneously started conversations with me, had accents which indicated they had been born in, or had recently come from, countries outside the United States.

I felt like I was in Berlin or Barcelona, where you could always count on meeting young people from all over the world at any music performance or cultural event, only this was a political action in the heart of New York’s financial district. I felt like I was in the midst of a global youth community, one I had certainly seen emerging during my travels and teaching — after all, I had helped organize a “Bronx Berlin Youth Exchange” — but that I had not expected to see at this particular protest.

But it was there, no doubt. And definitely made the discipline, determination, and camaraderie of the protesters that more impressive. But, as much as the age cohort and global character of the occupation seemed strange, it also seemed oddly familiar, though it took a while for that familiarity to sink in.

The longer I stayed at Liberty Plaza, the more it felt like the countercultural communities I had spent time in during the late 60’s, from Maine to Madison to Portland, Oregon, where discontent with war and a corrupt social system had bred a communal spirit marked by incredible generosity and openness to strangers.

During the years when I traveled the country regularly as a political organizer and revolutionary — 1968 to 1971 — I never had to stay in a hotel or pay for a meal in the more than 20 cities I visited. Every one of these cities had a countercultural community and I was always able to “crash” with people I knew or with people whose names I had been given by friends.

And I did the same for people in NYC. My apartment on West 99th Street was a crash pad for people from around the country who had come to New York for demonstrations, or for revolutionaries from other countries who had somehow gotten my name. I still remember making huge pots of chili for anyone who showed up — with Goya chili beans, canned tomatoes, chop mean, bay leaves, and chili powder. And it was not unusual for 20 or 30 to show up.

I had feared those days would never return — erased by decades of consumerism, materialism, and cheap electronic devices — but when I visited Liberty Plaza, I realized that the global economic crisis had recreated something which I often thought of as an artifact of my own nostalgia. Because right here in New York were hundreds of representatives of a whole generation of educated young people from around the world, numbering tens if not hundreds of millions of young people, who might never land in the secure professional jobs they had been promised or experience the cornucopia of material goods that came with them.

I had feared those days would never return — erased by decades of consumerism, materialism, and cheap electronic devices — but when I visited Liberty Plaza, I realized that the global economic crisis had recreated something which I often thought of as an artifact of my own nostalgia. Because right here in New York were hundreds of representatives of a whole generation of educated young people from around the world, numbering tens if not hundreds of millions of young people, who might never land in the secure professional jobs they had been promised or experience the cornucopia of material goods that came with them.

Described as a “lost generation” by economists, a critical mass of these young people, in cities throughout Europe and Latin America — and now right here in the United States — had decided to build community in the midst of scarcity, challenge consumerism and the profit motive, and call out the powerful financial interests whose speculation and greed had helped put them in the economic predicament they were in.

Serious questions remain about the long-term significance of this global movement. Would these middle class (or ex-middle class) protesters connect with the even larger group of people in their own countries — workers, immigrants, minorities — who had been living in poverty well before the current crash?

Would their community survive even a modest revival of the world economy, sending them back into a lifestyle of acquisitive individualism which the global consumer market depends on to yield profits? Could they connect with people in poor or working class neighborhoods who were already practicing communalism and mutual aid to create a truly multiracial, multi-class movement?

The jury is still out on all of those issues. But there are some promising signs. The chants of “We are all Troy Davis” during several of the movement’s marches. The increasing participation of labor unions in the protest. The involvement of more and more activists from the city’s Black and Latino neighborhoods in support of the Occupation.

And those who lived through the 60’s should remember this. Oppositional cultures of all kinds — ranging from hippie communities to the Black arts movement — represented the soil in which political protest flourished during those heady years.

And the same is true in this era. The emergence of a global youth counterculture should be seen as a powerful complement to, if not an actual component of, a global movement for freedom, democracy, and economic justice.

[Mark Naison is Professor of History and African American Studies at Fordham University and is principal investigator of the Bronx African American History Project. Naison, who was active with CORE and SDS in the 1960s, is the author of Communists in Harlem During the Great Depression and White Boy: A Memoir, and is co-editor of The Tenant Movement in New York City, and has written over 100 articles on African American politics, social movements, and American culture and sports. This article was also posted at With a Brooklyn Accent and Progressive America Rising.]